Introduction

Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) is a rare 46,XY difference/disorder of sex development (≈1/20,000–60,000 births) caused by pathogenic variants in the androgen receptor (AR; locus Xq11–12), resulting in absent androgen responsiveness in target tissues.1–3 Clinically, individuals have a female external phenotype with spontaneous breast development at puberty, sparse axillary/pubic hair, and absence of the uterus and ovaries.1,2,4 Diagnosis is typically suspected in primary amenorrhea and supported by a 46,XY karyotype, testosterone in the typical male range with inappropriately elevated luteinizing hormone (LH), and imaging that localizes undescended testes; when available, identification of a pathogenic or likely pathogenic AR variant confirms the etiology.1,4,5 Current management favors delayed gonadectomy after completion of spontaneous puberty, followed by estrogen replacement as part of multidisciplinary care.2,4,6,7

Case report

A 24-year-old woman, married, with no significant medical history, born to second-degree consanguineous parents and with two sisters affected by the same condition, presented for evaluation of primary amenorrhea and because of the familial context. On examination, she had well-developed breasts (Tanner IV; Figure 1A), very sparse pubic and axillary hair (Figure 1B), a short blind-ending vagina (cul-de-sac; Figure 1C), and a painless left inguinal swelling consistent with hernia.

Karyotype was 46, XY. Hormonal testing showed total testosterone 1.02 ng/mL (3.54 nmol/L; below adult male reference 8–30 nmol/L and slightly above adult female reference 0.3–1.8 nmol/L), LH 17 mIU/mL (= 17 IU/L; elevated vs female follicular 2–12 IU/L), FSH 2.10 mIU/mL (= 2.10 IU/L; low vs female follicular 3–10 IU/L), and estradiol 70.5 pmol/L (lower end of female follicular 70–530 pmol/L); tumor markers (AFP, hCG, LDH) were within normal limits. Pelvic imaging (patient-provided CT) confirmed absence of the uterus and ovaries and identified the gonads in the inguinal region. In our setting, computed tomography (CT) imaging was chosen because it was readily available and allowed precise localization of the gonads. Although ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging are generally preferred to minimize radiation exposure, CT is still used in some contexts, particularly when access to other imaging modalities is limited. (Figure 2).

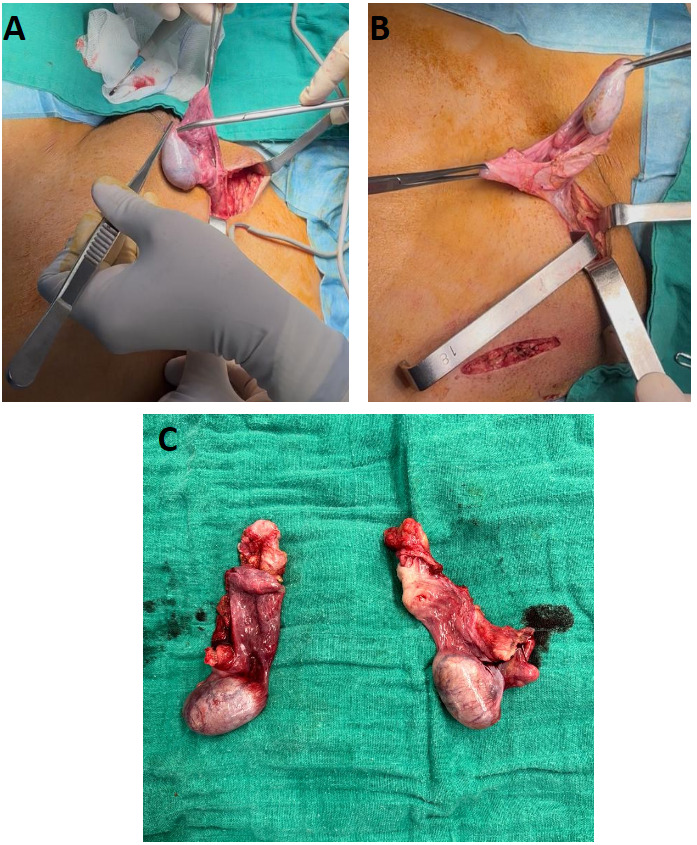

The patient underwent bilateral orchiectomy with McVay repair of the left inguinal hernia (Figure 3). Estrogen replacement therapy was initiated, and she performed vaginal dilation herself with guidance.

At 6-month follow-up, the course was favorable: good tolerance of estrogen therapy; no pelvic pain or inguinal masses; satisfactory perineal healing without infection; comfortable sexual intercourse after a structured dilation/pelvic-floor program; and appropriate psychosocial adjustment with specialist support, with no objective evidence of anxiety or depressive symptoms.

Discussion

Androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) is a 46,XY difference/disorder of sex development caused by pathogenic variants in the androgen receptor (AR), yielding a spectrum of end-organ androgen resistance. Phenotypes are conventionally classified as complete (CAIS), partial (PAIS), or mild (MAIS), often described along the Quigley scale to reflect degree of virilization.1

CAIS is rare (≈1:20,000–1:60,000 XY births). Individuals typically exhibit a female external phenotype with spontaneous breast development at puberty, sparse or absent pubic/axillary hair, and absent Müllerian structures due to fetal anti-Müllerian hormone from functioning testes.1,2 Familial clustering reflects X-linked inheritance.

Inactivating AR variants on Xq11–12 impair androgen signaling despite adequate ligand, explaining the dissociation between male-range androgens and female phenotype; many variants cluster in the ligand-binding domain. Molecular confirmation, when available, informs counseling and cascade testing in multiplex families.3,4

Presentation is commonly primary amenorrhea or detection of inguinal/labial gonads. The hormonal pattern shows testosterone in or near the adult male range with inappropriately normal/elevated LH, variably normal/low-normal FSH, and estradiol produced via aromatization. A 46,XY karyotype, imaging that confirms absent uterus/ovaries and localizes undescended testes, and identification of a pathogenic/likely pathogenic AR variant (when available) establish the diagnosis; care should be multidisciplinary.1,4,5

hCG stimulation can assess Leydig cell capacity in infants or selected 46,XY DSD, but is not routinely required in typical adolescent/adult CAIS when clinical, biochemical, and imaging features align; fibroblast androgen-binding assays are largely of historical interest.1,4

The initial work-up should distinguish CAIS from other 46,XY DSD, including 5α-reductase deficiency, gonadal dysgenesis/mixed gonadal dysgenesis, NR5A1-related DSD, and from 46,XX MRKH (uterine/vaginal agenesis) when the karyotype is unknown. Patterns of virilization, hair distribution, basal/stimulated androgens, and imaging guide this distinction.1,4

Ultrasonography of pelvis/inguinal canal is an appropriate first line; MRI is preferred when ultrasound is inconclusive, offering accurate localization of gonads and assessment for Müllerian remnants. CT is generally avoided for primary assessment because ionizing radiation rarely adds diagnostic yield. Diagnostic laparoscopy is useful when gonads are intra-abdominal or if simultaneous gonadectomy is planned.5

Contemporary data indicate that malignant transformation in CAIS is uncommon before and during adolescence and increases with age; a systematic review reported ~1.3% malignant lesions, all post-pubertal. These findings support deferring gonadectomy until after completion of spontaneous puberty, preserving endogenous estrogen for breast and bone development. In adults, surgery should follow shared decision-making, balancing age-related risk, patient preferences, and feasibility of surveillance.2

When chosen, bilateral gonadectomy is typically performed via minimally invasive/inguinal approaches with attention to hernia repair if indicated; outcomes are favorable in experienced centers.8

Estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) is indicated to maintain secondary sex characteristics, bone health, and overall well-being. Because there is no uterus, progestin is not required. Many centers favor transdermal 17β-estradiol for physiologic replacement and to mitigate thromboembolic risk; dosing is individualized with clinical/biochemical targets.6,7,9

Vaginal length may be short; non-surgical vaginal dilation is first-line and achieves high anatomic and functional success (~90–96%) with structured counseling. Vaginoplasty is reserved for those who do not meet goals with dilation or who elect a surgical option after informed consent. Long-term sexual function in CAIS is generally favorable with appropriate support.10,11

Studies demonstrate a propensity to lower bone mineral density in CAIS—particularly if gonadectomy occurs early or ERT is suboptimal—underscoring timely, physiologic estrogen replacement, lifestyle measures (calcium/vitamin D, weight-bearing exercise), and periodic DXA surveillance.12

Multidisciplinary, gender-affirming communication; discussion of fertility implications (no capacity for gestation; gamete potential absent); and access to peer/psychological support are integral to outcomes across the lifespan.1,4

Our patient’s phenotype (primary amenorrhea, sparse body hair, blind-ending vagina, 46,XY karyotype, inguinal testes) and management (post-pubertal bilateral gonadectomy, initiation of ERT, and first-line dilation) align with current best practice and likely contributed to the favorable 6-month sexual and psychosocial outcomes.1,2,4,6,10

A limitation of this case is the absence of androgen receptor (AR) genetic testing. Due to limited local resources and financial constraints, molecular analysis could not be performed. However, the clinical presentation, hormonal profile and imaging findings were highly suggestive of complete androgen insensitivity syndrome.

Despite these limitations, this case highlights the importance of timely diagnosis, individualized counselling and multidisciplinary management in patients with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome.

Conclusion

This case of Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome in a 24-year-old highlights the typical presentation of primary amenorrhea with absent Müllerian structures and a 46,XY karyotype, in a context of familial aggregation. Management with delayed bilateral orchiectomy, tailored estrogen replacement, and multidisciplinary support led to a favorable 6-month outcome. Ongoing follow-up remains essential to optimize bone health, sexual function, and psychosocial well-being.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication and any accompanying images.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding

Not applicable

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their special thanks to the Department of Radiology, Ibn Sina Hospital, University Hospital Center Ibn Sina, Mohammed V University in Rabat, Morocco, particularly Soumya Elgraini, M.D, Kaoutar Imrani, Ph.D, and Iitimad Nassar, Ph.D, for their valuable contribution to the imaging workup of this case.

.png)

_showing_right_left_inguinal_testis_(blue_arrow).png)

.png)

_showing_right_left_inguinal_testis_(blue_arrow).png)