INTRODUCTION

Colorectal neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are rare, representing less than 1% of all colorectal malignancies.1 They account for 5 to 7% of digestive neuroendocrine tumors.2 These tumors are characterized by rapid progression and aggressive behavior, with a high metastatic risk, often leading to diagnosis at advanced stages.1 The 3-year overall survival rate is estimated to range from 5% to 27%, with a significant risk of recurrence. As a result, chemotherapy remains a cornerstone of treatment.1 The incidence of NETs has increased, likely due to improved diagnostic techniques and the availability of highly specific and sensitive modalities, such as endoscopy, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasonography (US), and scintigraphy.3

CASE REPORT

It’s about a 58-year-old male with a medical history of poorly controlled diabetes and ischemic heart disease diagnosed seven years ago and currently under treatment. He presented with abdominal pain evolving over four months, initially relieved by antispasmodics, later associated with general deterioration, fatigue, and weight loss. He also reported intermittent episodes of diarrhea and constipation without signs of bowel obstruction.

Clinical examination revealed a stable patient, with mild abdominal distension and diffuse tenderness. Laboratory tests, including a complete blood count and electrolyte panel, was unremarkable. An abdominal ultrasound revealed a well-defined hypoechoic hepatic lesion located in segments II and IVa.

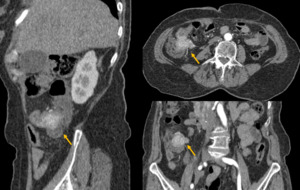

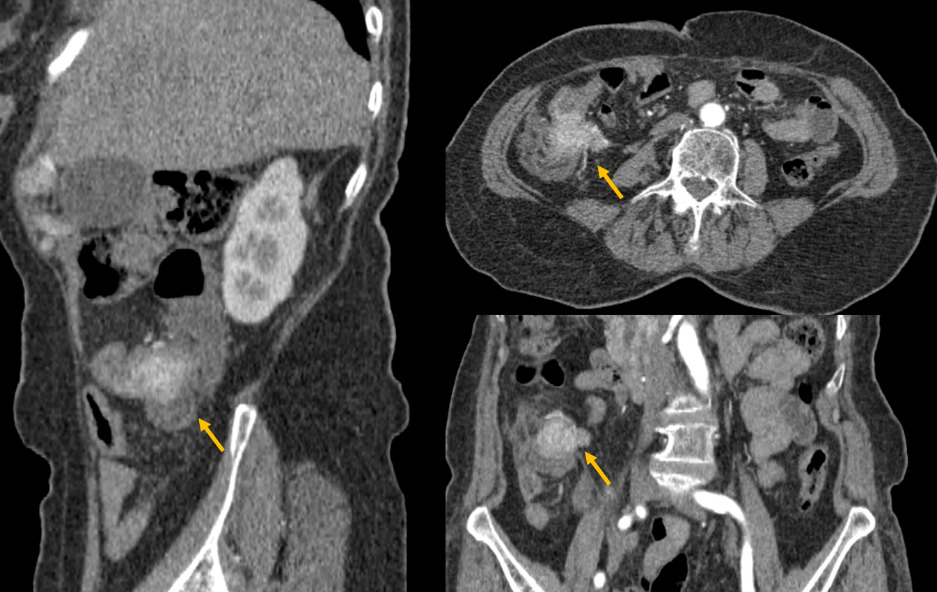

Therefore, he underwent a triple phase abdominal CT scan, revealing a poorly defined tumoral lesion in the ileocecal region, with irregular borders infiltrating the proximal colon and adjacent fat (Figure 1). The lesion showed early and intense enhancement in the arterial phase, suggesting hypervascularity. Additionally, CT-scan confirmed a well-circumscribed hypodense lesion in segment VI of the liver, which also showed early arterial enhancement (Figure 2).

Due to the nature of the enhancement, the diagnosis of a neuroendocrine colonic tumor with liver metastasis was considered. A biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the right colon. Given the high histological grade, the patient’s general condition, and the presence of hepatic metastasis, primary surgical management was not considered appropriate, and chemotherapy was proposed. Unfortunately, the patient passed away before starting treatment.

DISCUSSION

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are a rare group of malignant neoplasms arising from the neuroendocrine system, characterized by heterogeneous biological behavior and slow progression.4,5 They can occur in the upper or lower airways, thymus, digestive system, urinary tract, reproductive organs, breast, and skin. The digestive system and lungs are the most common sites of involvement.4

Isolated intestinal and pancreatic lesions form a heterogeneous family of tumors known as gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs). The most frequent locations are the intestine and colon-rectum (17.5%), followed by pancreatic (7%), gastric (6%), and appendiceal (3.1%) involvement.5

Compared to rectal neuroendocrine tumors, colonic lesions have a poorer prognosis with a lower survival rate.2These tumors can be classified as functional, secreting a peptide hormone responsible for carcinoid syndrome, or non-functional. At the time of diagnosis, more than 40% of patients with GEP-NETs present with hepatic metastases. Metastases to lymph nodes and bones are also commonly observed.5

Clinically, GEP-NETs can present with a variety of symptoms. They may be asymptomatic or manifest as abdominal pain, and in some cases, may lead to intestinal obstruction or intussusception, presenting as an occlusive syndrome.2 Carcinoid syndrome occurs in about 10% of patients with NETs, typically after the cancer spreads, especially when hepatic metastases develop. It results from excess serotonin or other hormones and presents with symptoms like diarrhea, facial flushing, palpitations, and asthma-like attacks.3

Histopathology remains the gold standard for diagnosis, and the WHO classification serves as a reliable prognostic tool for grading tumors, regardless of their size, location, or extent.1,4 This classification is based primarily on mitotic count and Ki-67 proliferation index.1 Therefore, they can be classified as low grade (G1): Ki-67 ≤ 2%, intermediate grade (G2): Ki-67 between 3% and 20%, and high grade (G3 or neuroendocrine carcinomas, NEC): Ki-67 > 20%.5

Histologically, these tumors exhibit organoid growth patterns, “salt-and-pepper” chromatin, and immunohistochemical evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation.4

NETs are characterized by a high malignant and invasive potential, resulting in a poorer prognosis compared to adenocarcinomas.1 This aggressive behavior often leads to a delayed diagnosis, with approximately 57.9% to 67.5% of cases detected at stage IV, in contrast to 25.2% for adenocarcinomas.1 The rapid growth of the tumor at the time of diagnosis reflects its high proliferative rate, with significant potential for local invasion and distant metastatic spread.1 Tumor grade is strongly correlated with overall survival, and recurrence risk increases with higher grade and TNM stage.4

Patients with suspected NETs should undergo biochemical testing.3 The most commonly used markers for diagnosis and follow-up are chromogranin A (CgA), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA).3 CgA and NSE are primarily used to assess tumor progression and response to therapy.3 CgA is elevated in approximately 70% of NETs, including non-functional types, though its specificity (86–95%) is limited due to elevations in non-tumoral conditions such as renal failure, atrophic gastritis, or proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use, despite a sensitivity of 67–73%.3 Elevated CgA is also associated with poor prognosis. NSE has high specificity (100%) but low sensitivity (32%).3 Urinary 5-HIAA, a serotonin metabolite, is a key marker for carcinoid syndrome, with a sensitivity of 65–75% and a specificity of 100%.3 In our case, biological examination wasn’t done due to lack of resources.

Imaging plays a key role in localizing the primary tumor, staging, detecting metastases, and assessing resectability and treatment response.

Contrast-enhanced CT and MRI are among the most commonly used modalities.6 CT is typically the first-line investigation for suspected neuroendocrine tumors, useful for staging and surgical planning.7 Primary gastrointestinal lesion as well as their metastases typically appear hyperenhancing with intravenous contrast, best seen in the arterial phase of a triple-phase CT.7

MRI is particularly effective in detecting hepatic metastasis.7 Indeed, studies show MRI has a higher sensitivity (95.2%) than CT (78.5%) and OctreoScan (49.3%) for liver metastasis detection.7 While less effective than CT for identifying primary small bowel NETs and lymphadenopathy, MRI is superior for evaluating pancreatic NETs.7 Moreover, contrast-enhanced and diffusion-weighted MRI an help identify bone metastases and assess treatment response.6

FDG PET has limited use in low-grade NETs due to their low metabolic activity, resulting in poor tracer uptake.7 However, it is useful in high-grade tumors, which show greater FDG avidity and can indicate more aggressive disease.7

Somatostatin receptor-based imaging is key in NET diagnosis due to the high expression of somatostatin receptors (SSTRs) on tumor cells.7 The traditional OctreoScan, using ¹¹¹In-labeled octreotide, is now paired with SPECT/CT for improved accuracy.7 More recently, ⁶⁸Ga-labeled PET tracers (e.g., DOTATOC, DOTANOC, DOTATATE) provide superior resolution when combined with CT.7 These techniques help in tumor detection, staging, follow-up, and selection of patients for peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT).7 It should be noted that long-acting octreotide should be paused 4–6 weeks before imaging.7 OctreoScan images are acquired at 4 and 24 hours post-injection, while ⁶⁸Ga PET/CT is done 60 minutes after tracer administration.7

While conventional cross-sectional imaging (CT/MRI) remains essential for evaluating treatment response, SSR PET offers complementary information in some cases.6

For follow-up, CT and MRI are more effective than SSR/PET imaging for accurate lesion measurement due to their superior spatial resolution and soft tissue contrast.6 This is crucial for monitoring neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs), which often grow slowly and require precise, serial assessments to detect disease progression.6

Although standardized management guidelines are still lacking, early-stage neuroendocrine tumors are typically treated with surgery.1 In advanced stage, chemotherapy plays a fundamental role and may be combined with stenting in cases of bowel obstruction to improve life quality. Platinum-based regimens are commonly used, with a reported response rate of 42%.1

Management of hepatic metastases depends on tumor size and grade. Surgery remains the curative approach for well- or moderately-differentiated (G1–G2) and resectable tumors. However, locoregional therapies such as embolization and chemoembolization are increasingly employed to prolong survival in unresectable cases.5 Liver transplantation may also be considered, with a 5-year survival rate exceeding 70%. In unresectable metastases or high-grade tumors, systemic therapies—including somatostatin analogs, chemotherapy, interferon-alpha, and targeted therapies—are considered.5 In our patient with high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, curative treatment was not an option, and chemotherapy was deemed the most appropriate approach. Unfortunately, the patient had a short survival.

CONCLUSION

Colorectal neuroendocrine tumors are rare, often aggressive neoplasms with a high metastatic potential at diagnosis. Their management requires a multidisciplinary approach integrating pathology, advanced imaging, and personalized treatment strategies. This case of high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma with hepatic metastasis highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges posed by these tumors. Despite early identification, the patient’s rapid clinical decline illustrates the urgent need for improved strategies in early detection and management of high-grade NETs.

PATIENT CONSENT

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the legally authorized representative of the patient.