INTRODUCTION

Cellulitis is a common medical condition involving the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Untreated or neglected cases can lead to unfavorable outcomes. Cellulitis often follows infections with Streptococcus and Staphylococcus bacteria, among which Staphylococcus aureus, including MRSA, is responsible for many cases.1 The main clinical features of cellulitis include redness, tenderness, swelling, warmth and sometimes fever and toxic symptoms. Antibiotic therapy remains the standard of care for patients with cellulitis, and delays in starting therapy or suboptimal care can result in a spectrum of complications, such as: abscess formation, sepsis, and in rare but life-threatening cases, necrotizing fasciitis.2 Interventions such as: incisions and drainage or debridement are absolutely necessary for complicated cases.

Following a diagnosis of cellulitis, the administration of antibiotics is of paramount importance. Meanwhile, in selected cases surgical intervention improves patient prognosis.3 In a subset of patients with necrotizing fasciitis and abscess formation, interventions such as surgical debridement or drainage accelerate the recovery process.4 Prolonged hospitalization and recurrent admissions are common among a set of cellulitis patients. Although established treatment guidelines prove the effectiveness of management, for the above-mentioned reasons – further research will address the factors influencing the outcomes and upgrade treatment strategies.

Diabetes, peripheral vascular disease (PVD) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) are common among the Sri Lankan population. The above-mentioned comorbidities complicate the resolution of cellulitis and add a significant burden to healthcare.5 Complicated and severe cellulitis is common among the diabetic population. Diabetes interferes with immune function, which in turn disturbs the wound healing steps.6 Long standing diabetic patients and older adults are known to suffer from peripheral vascular disease, which can reduce the blood flow and impair the wound healing.7 Access to healthcare, timely healthcare-seeking behavior and early treatment are often lacking in Sri Lanka, which increases the burden of cellulitis cases in the country.

Clinical studies focusing on the outcomes of patients with cellulitis managed in the Sri Lankan setting are not comprehensive despite cellulitis being a significant burden to health care. The knowledge gap on this topic prevents the identification of factors that affect patient outcomes and the evaluation of best treatment strategies. Studies in Western countries have revealed that cellulitis complications are often observed in those with comorbidities such as diabetes, PVD, CKD and delayed treatment seeking.8 The results of these studies cannot be simply applied to Sri Lanka because disease patterns, healthcare infrastructure, and treatment approaches are not the same.

Treating severe cases of cellulitis requires attention in surgical wards, as these infections require both medical and surgical care. In such situations, early administration of intravenous antibiotics and meticulous surgical intervention will definitely improve outcomes.9 As a result, looking at the length of hospital stay and rate of readmission helps determine the effect of cellulitis on the healthcare system and the success of treatment. These factors have not received enough attention through research yet. The Sri Lankan population faces unique challenges such as delayed access to healthcare, diverse levels of antibiotic resistance and varying health problems.

This study was designed to determine the clinical effects of cellulitis treatment in patients admitted to surgical wards in Sri Lanka and to identify the factors that predict worse outcomes. This research provides valuable knowledge about how different variables (such as comorbidities, the timing of medical interventions and treatment strategies) influencing the outcomes of cellulitis treatment can be managed more effectively. Furthermore, analyzing the clinical outcomes regarding resolution rate, potential complications, and mortality rate will assist physicians in improving individualized care for patients with cellulitis, which is ultimately provided to Sri Lankan hospitals. Moreover, the results of this study can be utilized to improve care for cellulitis patients in resource-limited settings, such as Sri Lanka. Understanding the factors that affect recovery in patients with cellulitis will support healthcare providers and policymakers in optimizing resource use, updating treatment protocols and enhancing care protocols for patients admitted to surgical units due to the disease. The results are expected to reduce the burden of cellulitis on the healthcare system, reduce complications, and enhance the overall well-being of patients in Sri Lanka.

This study aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes of patients admitted with cellulitis to surgical wards, identify risk factors for poor prognosis, and assess the impact of comorbidities and treatment approaches.

METHODS

Study Design

A retrospective cohort study was conducted on 120 patients admitted with lower limb cellulitis over a period of 6 months (February 2025 to July 2025) to a surgical unit of the National Hospital of Sri Lanka which is the largest tertiary care hospital of the country.

Case Definition

Cellulitis was diagnosed on clinical grounds, including acute onset of localized erythema, warmth, swelling, and tenderness of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, with or without systemic features such as fever or leukocytosis. Adjuncts like (Ultrasound/CT/MRI) used selectively to exclude deep infection or alternative pathology, and microbiological confirmation from pus, wound swabs, or blood cultures were recorded when available but it is not mandatory.

Necrotizing fasciitis was diagnosed on the basis of rapidly progressive pain and swelling disproportionate to cutaneous findings, along with clinical signs such as bullae, necrosis, or crepitus. Radiological evidence of fascial involvement (gas in fascial planes on X-ray/CT) and intraoperative findings of necrotic fascia with “dishwater pus” were considered confirmatory, while histopathological reports were used in support where available.

Sepsis was classified according to Sepsis-3 criteria, namely suspected or confirmed infection plus an acute increase of ≥2 points in the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score.

Inclusion Criteria

-

All patients aged 18 years and above who were diagnosed with lower limb cellulitis and admitted to a surgical ward of National Hospital of Sri Lanka.

-

Patients with cellulitis of any severity, including mild, moderate, and severe cases that required hospital admission.

-

Patients who had complete medical records, including details of diagnosis, treatments, and outcomes.

Exclusion Criteria

-

Patients with incomplete medical records, which would hinder accurate data collection.

-

Patients diagnosed with other major infections or conditions that could significantly affect immune response (e.g., HIV/AIDS, malignancies, severe immunosuppressive treatments).

-

Patients with cellulitis resulting from non-bacterial causes, such as fungal or viral infections, as the focus of the study is on bacterial cellulitis.

-

Patients with mimicking conditions, including deep vein thrombosis, erysipelas, stasis dermatitis, gout, contact dermatitis, and vasculitis.

Data Collection

The data were extracted from hospital bed-head ticket (BHT), with the following key variables being collected:

Demographic Information

Age and gender of the patients to examine the distribution of cellulitis cases across different age groups and genders. Medical history, including comorbid conditions such as diabetes, peripheral vascular disease (PVD), hypertension, and any other chronic conditions that may impact the course of cellulitis.

Grading of Cellulitis

CREST standards for grading cellulitis were used to determine the degree of limb involvement.

Clinical Outcomes

Resolution of cellulitis: The primary clinical outcome, indicating whether cellulitis resolved completely, partially resolved, or worsened during hospitalization.

Complete resolution – no symptoms/signs and normalized labs at discharge.

Partial resolution – symptom improvement but not complete, still requiring follow-up.

Complications: The occurrence of complications such as abscess formation, sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis, or gangrene. The presence of these complications will be used to evaluate the severity of cellulitis and its management.

Mortality rate: The number of patients who died during their hospital stay due to cellulitis or related complications.

Duration of hospital stay: The length of time each patient stayed in the hospital, which will help assess the severity of the infection and the effectiveness of the treatment provided.

Readmission definition

Readmissions were included only at the National Hospital of Sri Lanka (NHSL). Only unplanned readmissions were included; scheduled follow-up or planned procedures were excluded. Readmissions were restricted to those that were infection-related (recurrent cellulitis, abscess, sepsis, or related wound complications).

Risk Factors

Comorbidities such as diabetes and PVD, as these conditions are known to impact the progression and outcome of cellulitis.

Delayed presentation: Whether patients sought medical attention more than 72 hours after the onset of symptoms, as delayed treatment is linked to more severe outcomes.

Type of treatment received (whether surgical interventions such as debridement were performed, or if patients were treated with medical therapy alone).

Treatment Approaches

Antibiotics used: Details on the types of antibiotics prescribed, including empirical antibiotic therapy and any modifications made based on culture results.

Surgical interventions: Data on whether debridement or other surgical procedures were performed, and if so, the timing and type of surgical interventions.

Other medical therapies: Any additional treatments, such as wound care procedures, use of wound dressings, or adjunct therapies used to manage cellulitis.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using a combination of descriptive and inferential statistical methods in SPSS version 25.

Descriptive Statistics

Demographic and clinical characteristics: Descriptive statistics (e.g., mean, median, percentages) were used to summarize the demographic details (age, gender) and clinical characteristics (comorbidities, type of treatment received) of the patients included in the study.

The frequency of complications, resolution rates, and mortality rates were also be summarized descriptively to provide an overall view of the clinical outcomes.

Continuous variables were summarized as median (interquartile range [IQR]) due to skewed distributions, while categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages.

Logistic Regression

To assess the relationship between potential risk factors (e.g., diabetes, PVD, delayed presentation) and poor outcomes (e.g., complications, mortality), logistic regression were employed. This method will allow for the identification of significant predictors of poor clinical outcomes while controlling for potential confounders (e.g., age, gender, comorbidities).

The odds ratios (OR) were calculated, with confidence intervals (CI) and p-values to determine the strength of the associations between risk factors and outcomes.

Comparative Analysis

A comparative analysis were conducted between the groups of patients who received surgical interventions (e.g., debridement) and those who were treated with only medical therapy. This analysis helped to determine the effectiveness of surgical management compared to conservative approaches.

Chi-square tests (for categorical variables) and t-tests (for continuous variables) were used to compare the clinical outcomes (resolution rates, complications, hospital stay duration) between the two treatment groups.

To identify independent predictors of complications, we performed multivariable logistic regression with complication (yes/no) as the dependent variable. Candidate covariates included: Age (>65 years vs ≤65), Sex, CREST grade (III–IV vs I–II), Diabetes mellitus, Chronic kidney disease (or elevated creatinine/eGFR impairment), Admission WBC (>11 × 10⁹/L vs normal), Admission creatinine (>1.3 mg/dL vs normal), Pre-admission antibiotics (yes/no), Delayed presentation (>72 hours from symptom onset).

Variables were retained in the final model if clinically relevant or statistically significant (p < 0.10 on univariate analysis). Results are reported as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Length of stay (LOS) was modeled separately using negative binomial regression, with surgical intervention, CREST grade, diabetes, and renal function included as covariates. Incidence rate ratios (IRR) with 95% CI were reported. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

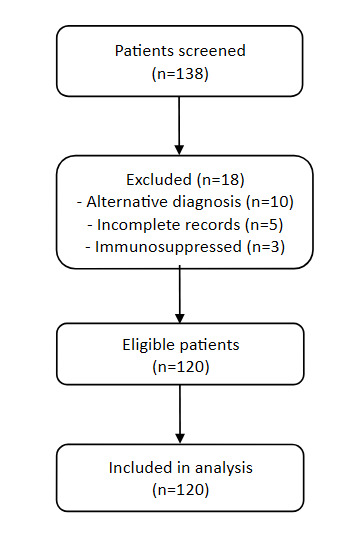

A total of 138 patients were screened for lower limb cellulitis during the study period. Eighteen were excluded, 10 with alternative diagnosis, 5 with incomplete medical records and 3 with severe immunosuppression. The final sample included 120 patients for analysis. The median age was 59 years (IQR 48-68) and 54.2% were male. The majority (87.5%) resided in urban areas. Diabetes mellitus was the commonest comorbidity (54.2%) noted in my population, followed by hypertension (40%), chronic kidney disease (9.2%), varicose vein (5.0%) and lymphedema (4.2%). As per CREST grading – Majority (43.3%) presented with Grade II cellulitis, 24.2% with Grade I, 24.2% with Grade III and 8.3% with Grade IV. The laboratory abnormalities were common where leukocytosis occurred in 74.2%, neutrophilia in 75.0%, increased CRP in 85.0% and increased creatinine in 22.5%.

In this study, 74.2% (n = 89) had one or more comorbidities, with diabetes mellitus (54.2%) and hypertension (40%) being the most prevalent. Other comorbidities included chronic kidney disease (9.2%), varicose veins (5%), lymphedema (4.2%), and neuropathy (4.2%). The most common reported symptoms were swelling (95%) and pain (94.2%), followed by redness (75.8%) and fever (74.2%). Blistering was reported in (25.8%) of the patients, which may indicate more severe or advanced infection and rarely, inguinal lymphadenopathy and toe gangrene were observed in (0.8%) of the patients. These findings represent classic cellulitis with occasional severe or atypical manifestations. Identifiable predisposing factors were noted in 70.8% (n=85) of the patients, with skin ulcers being the most common (67.1%), followed by fissures (17.6%), trauma (11.8%), and toe web infections (3.5%). These findings highlight the critical role of skin barrier disruption in the pathogenesis of cellulitis.

All patients received intravenous antibiotics. Empiric antibiotics included anti-staphylococcal Penicillin (65%), Cephalosporins (20%) and broad-spectrum antibiotics with MRSA coverage (15%). Culture-directed antibiotic change occurred in 22%. In my study, half the patients (n=60) required surgical interventions – incision & drainage in 22.5%, debridement 16.7%, fasciotomy in 6.7% and amputation in 4.2%.

Complete resolution occurred in 66 patients (55%), partial resolution in 20 (16.7%) and complications in 34 (28.3%). Complications included abscess formation (11.7%), necrotizing fasciitis (8.3%), sepsis (7.5%) and one in-hospital death (0.8%). Median hospital stay was 6 days (IQR 4-9). The patients who had surgery stayed longer (median 9 days, IQR 7-12) than the group treated conservatively (median 4 days, IQR 3-6). Fourteen patients (11.7%) experienced unplanned infection-related readmission within 30 days.

On multivariable logistic regression, three factors were independently associated with complications. Patients presenting with higher CREST grade (III–IV vs I–II) had increased odds of complications (aOR 3.25, 95% CI 1.42–7.45, p = 0.005). Elevated WBC count at admission was also associated with significant complications (aOR 2.11, 95% CI 1.01–4.43, p = 0.048). Similarly, elevated serum creatinine (>1.3 mg/dL) was strongly associated with complications (aOR 3.89, 95% CI 1.62–9.32, p = 0.002). Age, sex, diabetes, CKD, CRP, pre-admission antibiotic use, and delayed presentation were not significant statistically.

On multivariable negative binomial regression analysis, surgical intervention (IRR 2.18, 95% CI 1.62–2.92, p < 0.001), higher CREST grade (III–IV) (IRR 1.34, 95% CI 1.09–1.64, p = 0.006), and diabetes mellitus (IRR 1.28, 95% CI 1.01–1.62, p = 0.043) were identified as independent predictors of prolonged length of stay. Other factors like age, sex, renal function, delayed presentation, and pre-admission antibiotics, were not significantly associated with hospital stay duration.

In my study, 12% (n=14) had unplanned readmission to the national hospital within 30 days of discharge. All of these admissions were related to lower limb cellulitis. These findings can inform hospital performance evaluations and may also reflect the quality of postdischarge care or patient compliance with treatment plans. However, further analysis is needed to identify specific factors contributing to the observed 12% readmission rate.

DISCUSSION

Advanced age is commonly linked with poorer outcomes in patients with cellulitis due to immunosenescence and the presence of multiple comorbidities.6 Nevertheless, age over 65 years was not found in our research to be significantly correlated with complications. This could be due to the relatively low mean age of our cohort (59 years), and a larger sample size is needed to detect more subtle associations. Additionally, other confounding factors such as treatment strategies and comorbid conditions, likely influence outcomes in elderly individuals.

Although delayed presentation (>72 hours from symptom onset) has been shown in previous studies to be a risk factor for poor outcomes,8 our findings did not reveal a statistically significant association. This difference can be attributed to the fact that over-the-counter antibiotics are extensively used and available in the local population which potentially decreases the severity of the disease outcome even before the admission to the hospital. Moreover, the presence of comorbidities in conjunction with delayed presentation may have a more substantial role in determining outcomes, suggesting the need for a multifactorial approach in risk assessment.

Predictors of complications

Multivariable analysis revealed a significant correlation between increased CREST grade, leukocytosis, and elevated serum creatinine were independently associated with complications. These results imply that disease severity, systemic inflammation, and renal dysfunction are clinically relevant markers of poor outcome in cellulitis. Prior studies in high-income countries have similarly shown that severity scores and laboratory parameters predict progression to sepsis or need for surgical intervention. Our findings extend this evidence to a South Asian context, where diabetes and chronic kidney disease are highly prevalent. Interestingly, diabetes itself was not independently associated with complications after adjustment, indicating that renal impairment may be a stronger driver of risk than diabetes alone.

Predictors of length of stay

The severity of cellulitis and treatment modality influenced the length of stay (LOS). Surgical intervention, higher CREST grade, and diabetes were all associated with prolonged hospitalization. While surgery likely reflects more severe or complicated presentations, the association with diabetes may reflect impaired wound healing and slower response to treatment. These associations reinforce the importance of early detection of high-risk category and indicate the potential role of standardized surgical decision-making to optimize bed utilization in tertiary hospitals.

Readmission

The 30-day readmission rate in this study was 12%, and all were for cellulitis-related reasons. This is a comparable rate to international figures (10–15%) and suggests opportunities for improved discharge planning, patient education, and structured follow-up. Readmissions are increasingly recognized as indicators of both disease severity and health system performance. Further prospective studies are warranted to identify modifiable factors contributing to readmission in Sri Lanka, including antibiotic compliance, glycemic control, and wound care after discharge.

Clinical and Public health implications

Our findings have number of implications in practice. First, CREST severity grading combined with admission laboratory markers (WBC, creatinine) may provide a simple risk stratification tool which is easy to use and allows one to identify patients at highest risk of complications and prolonged stay. Second, the strong association between renal dysfunction and complications reiterate the need for early renal assessment and careful antibiotic dosing. Third, the fact that surgical intervention and LOS were high among surgically candidates is a point of concern which supports the value of effective surgical referral and standardized peri-operative practices. Lastly, unplanned readmissions require well-organized outpatient follow-up and preventive programs, especially among patients with diabetes.

LIMITATIONS

First, the study was conducted as a retrospective cohort study in a single surgical unit of the National Hospital of Sri Lanka (Tertiary care hospital), and the findings may not be generalizable to other settings. It also reflects potential selection bias. Second, the sample size could be a limiting factor, although adequate for preliminary analysis, further research needed with larger and more diverse populations in needed. Third, we only focused on the admission CRP measurement and subsequent values not addressed, which is one of the limitations in defining the role of CRP. Fourth, since the eGFR was not consistently available and therefore couldn’t analysis the role. Finally, patients admitted here tend to be older, urban and with a higher prevalence of comorbidities compared to general community.

Author contributions

All the authors contributed to conceptualizing, designing, and carrying out the study.

Funding

This study did not receive any grants from any funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the ERC/NHSL.