Introduction

Giant Cell Arteritis

It is estimated that the lifetime risk of giant cell arteritis is 1% for women compared to 0.5% for men in United States.1 The prevalence of giant cell aortitis is much less common, although still more likely to occur in women compared to men; estimated prevalence of 304 per 100,000 in women and 91 per 100,000 per men.2

Giant cell arteritis typically affects patients >50 year of age and classic symptoms can include headache, temporal artery tenderness, jaw claudication or acute visual disturbance/loss and constitutional symptoms. Infrequently, patients can present with serious cardiovascular events or conditions, including: stroke and myocardial infarction, aortic aneurysm or dissection.3,4

Giant cell arteritis with typical cranial symptoms can later manifest as aortitis or aorta dilatation or aneurysm secondary to chronic subclinical inflammation. Aortitis was detected median 3.7 years after initial giant cell arteritis presentation in one study.5 Aortic dilatation (40-43 mm) was detected within 5 years of initial giant cell arteritis presentation in another study.6

Giant Cell Aortitis

A prior study highlights that giant cell aortitis in the majority of cases manifests with less cranial symptoms than giant cell arteritis and hence the name of “isolated giant cell aortitis”.7 Giant cell aortitis also differentiates itself from giant cell arteritis, in its need for longer duration corticosteroid use than giant cell arteritis, respectively median 4.5 vs 2.2 years.7 During followup of giant cell aortitis, the need to remain vigilant for potential aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection complications is essential. In a retrospective study of 136 giant cell aortitis patients with median follow-up of 52 months, aneurysm and dissection were identified, respectively in 21% and 5%.8 Finally, even after successful surgical intervention, patients with giant cell aortitis require continued longitudinal followup with aorta imaging. In a retrospective review of 184 patients who required aortic surgery and giant cell aortitis was diagnosed by pathology, reoperation on aorta was observed at rates of 3.9%, 7.1%, 12.8% and 12.8%, respectively at 1, 5, 10, and 15 years.9

Case Presentation

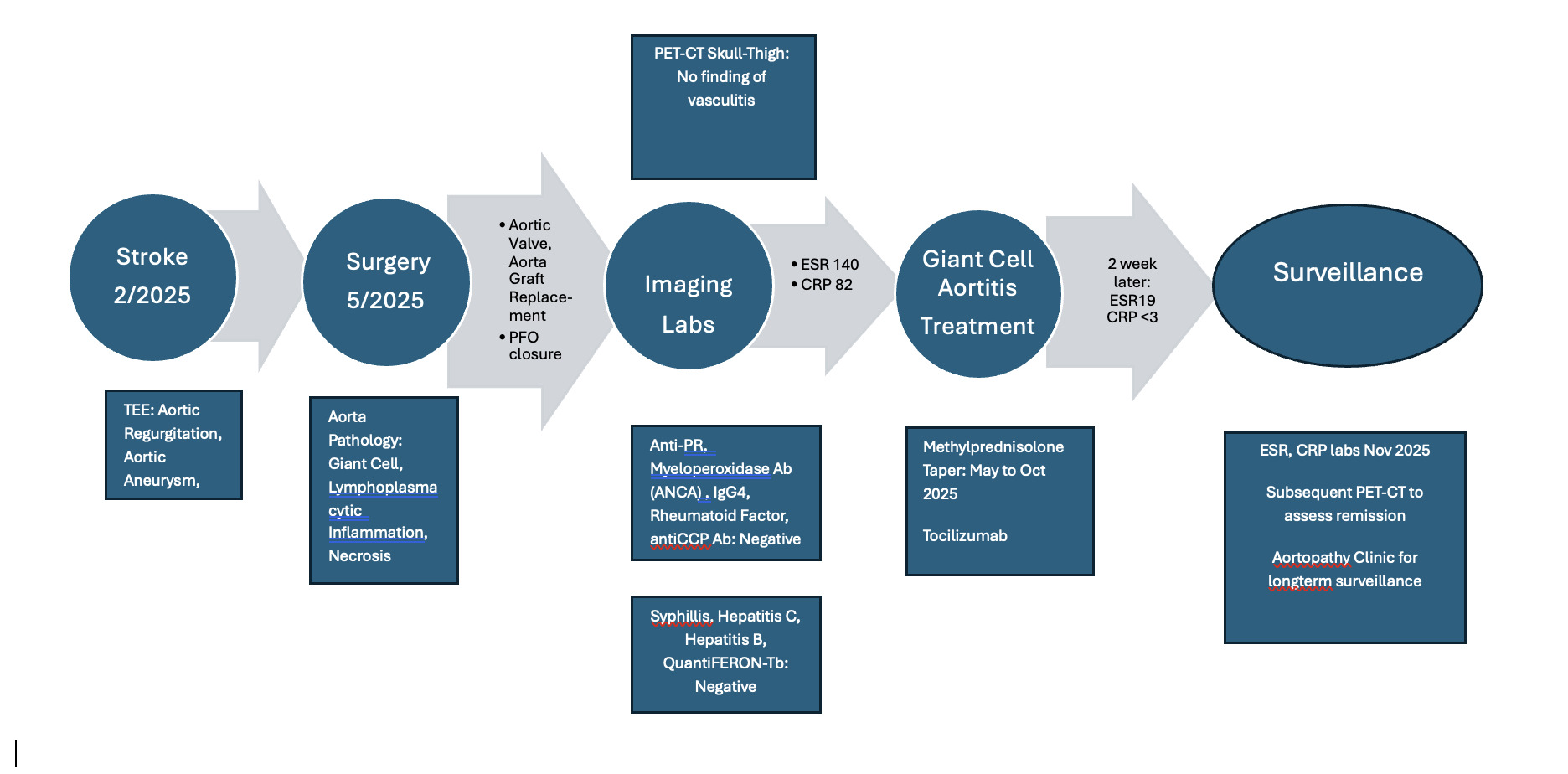

A 46-year-old female initially presented with speech difficulty, and right face numbness while on vacation in Mexico. Outside brain MRI showed small left parietal lobe infarct. She presented to cardiology clinic after outside hospitalization; she had recovered without neurologic deficit. Over one to two years she recalls fatigue and windedness with exertion climbing 15 steps in her home. She denied fevers or chills.

Blood pressure: 125/69, heart rate 66, pulse oximetry 99%, height 160 cm, weight 62 kg, BMI 24. Physical examination revealed diastolic decrescendo murmur notable at right sternal border.

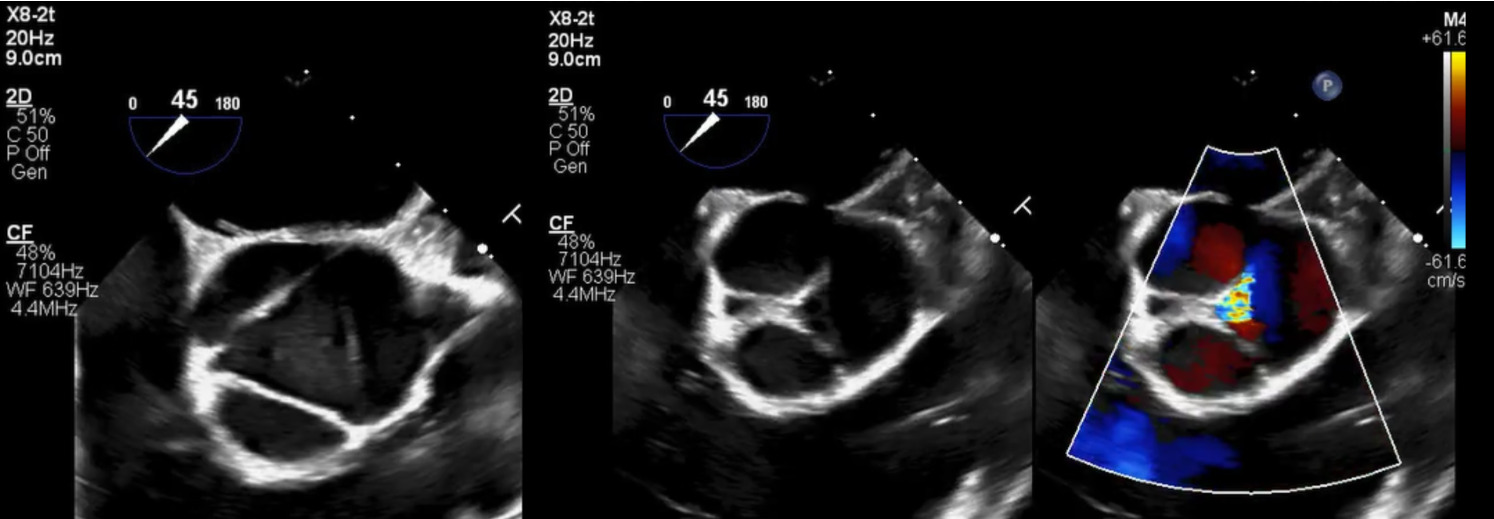

Brain and neck magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) showed no acute or significant vascular abnormality. Transesophageal echocardiogram showed severe aortic regurgitation, trileaflet thickened aortic valve, enlarged ascending aorta 45 mm, normal left ventricular systolic function and patent foramen ovale (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). Calculated aorta size index (aortic size cm/body surface area m2) was moderate-severely increased, 2.7 cm2/m2. Mild immobile atherosclerosis of the aorta was noted.

Although transesophageal echocardiogram identified mild immobile thoracic aorta atherosclerosis and a patent foramen ovale (PFO), two potential sources for embolic stroke, the definitive etiology of stroke was not clear. Extended two-week rhythm monitor showed no atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Hypercoagulable lab workup was negative. Lipoprotein(a) was elevated at 118 nmol/L.

Due to severe aortic regurgitation with limiting dyspnea on exertion, aortic valve replacement surgery was recommended, with adjunctive aortic root replacement for aortic aneurysm and closure of PFO. Pre-operative cardiac catheterization showed normal coronary arteries.

Intraoperative findings revealed significant dilated aortic root and abnormal aortic tissue. Cardiothoracic surgeon described the aortic tissue as thin, somewhat inflamed, discolored/ purplish, and noted visible plaques lining the intimal layer. During dissection and manipulation of the heart the patient developed atrial fibrillation. The operative team was able to convert patient to normal sinus rhythm by vagal maneuvers and placing ice on the sinoatrial node. Cardiothoracic Surgery subsequently performed a 23 mm Onyx aortic valve with aortic graft Bentall replacement and patent foramen ovale closure. Cardiothoracic Surgery also elected to place a left atrial appendage clip given intraoperative atrial fibrillation.

Aortic root pathology showed significant destruction of aortic wall with extensive necrosis and fibrosis (Figure 4).

Higher magnification revealed transmural lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and scattered multinucleated giant cells (Figure 5).

With pathology confirmed aortitis, post-operative C-reactive protein and Sedimentation rate levels were checked and elevated respectively at 82 mg/L and140 mm/h. Both levels were elevated as expected with active aortitis, however difficult to exclude some contributor of post-surgery inflammation. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the chest, abdomen and pelvis showed no other arterial abnormality, aside from expected postoperative changes to aortic root and aortic valve. PET-CT skull to thigh showed no significant fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the vasculature to support PET diagnosis of vasculitis.

Differential Diagnosis

The key differential diagnoses of histological findings were Giant Cell Aortitis and Takayasu arteritis. Takayasu arteritis is most common under age of 40 years old, although 2022 American College of Rheumatology/EULAR classification criteria recognize age spectrum to span up until age of 60 years old. Takayasu arteritis classically can present with arm or leg claudication symptoms and demonstrate imaging features of vasculitis involving aortic branch vessels,abdominal aorta, renal or mesenteric vessels.

IgG4-related aortitis was recognized as another important disease in the differential diagnoses. IgG4-related aortitis is typically characterized by tissue lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and storiform fibrosis, often with elevated serum IgG4 levels and extra-aortic involvement of biliary tract, pancreas, or bilateral submandibular glands. This patient’s IgG4 level was normal, 11.6 (Normal range 2.4-121 mg/dL.) and her PET-CT imaging did not show other organ involvement.

ANCA associated large vessel vasculitis was considered however associated levels of Anti-PR Ab and Myeloperoxidase Ab were negative. Rheumatoid arthritis–associated aortitis was also considered however Rheumatoid Factor Ab, Cyclic citrullinated peptide Ab, Antinuclear Ab were negative. In addition, this patient did not have any clinical features to indicate inflammatory arthritis.

Infectious etiologies for aortitis were excluded by serology, including: Syphilitic aortitis (typically a late manifestation of tertiary syphilis particularly in older adults) by negative Syphillis Total Ab, Mycobacterial infection by negative QuantiFERON-Tb, Coccidioidomycosis by negative cocci IgG and cocci Ig M,Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C, by negative Hep B sAg and HCV Ab.

Discussion with the rheumatology team concluded that the patient’s case in summary was most consistent with giant cell aortitis diagnosis.

Treatment Response

Prednisone 60mg daily was started postoperatively for one week, subsequent plan of 50 mg daily for one week, 40 mg daily for one week, and then 30 mg daily. Tocilizumab 162 mg every week was planned to initiate as outpatient.

Two weeks post-discharge, she was readmitted to hospital with dizziness and fatigue symptoms. CRP was <3.0, Sedimentation rate was 19, both levels normal. Symptoms were ultimately attributed to prednisone and she was switched to methylprednisolone 40 mg for 5 days, then 32 mg daily with good clinical response.

On outpatient cardiovascular clinic followup she reported feeling well. She continues on aspirin 81 mg daily and coumadin for mechanical Onyx aortic valve, INR goal 2-3 for first three months and then maintenance INR goal of 1.5-2. Rheumatology followup planned prednisolone taper completion over 4 months. At 5 months post cardiac surgery, CRP and ESR labs will be repeated and subsequent PET-CT to assess for aortitis remission. A concise timeline of patient’s clinical course is summarized in Figure 6.

Discussion

Diagnosis of Giant Cell Arteritis and Aortitis

In conjunction with clinical history, giant cell arteritis is supported by laboratory, imaging, and biopsy criteria data. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology Laboratory, Imaging and Biopsy Criteria (for Giant Cell Arteritis) define these supportive criteria as below10:

-

"Maximum erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) ≥50 mm/hour or maximum c-reactive protein (CRP) ≥10 mg/liter

-

Positive temporal artery biopsy or halo sign on temporal artery ultrasound

-

Bilateral axillary involvement (stenosis, occlusion, aneurysm) on noninvasive/invasive angiography or ultrasound

-

FDG-PET activity throughout descending thoracic, abdominal aorta (by visual identification greater than liver uptake)."

ESR and CRP levels are typically elevated with giant cell arteritis and giant cell aortitis; In only 3% cases, both ESR and CRP labs are normal.11 Temporal artery biopsy is useful for pathological diagnosis, recognizing that yield of biopsy is lower in giant cell aortitis than classic giant cell arteritis. In one study of 79 patients with aortitis or large vessel involvement, temporal artery biopsy yielded giant cell arteritis pathologic diagnosis in 41 patients (52%)7

Expedited CT or MRI imaging of the entire aorta and branch vessels is recommended, which can demonstrate mural thickening, edema, or inflammation or branch vessel stenosis. If available, 18F – FDG positron emission tomography (PET) can be combined with CT, to further highlight active inflammation. Aorta and branch vessel vasculature imaging is recognized as a complementary diagnostic tool, given some patients with active inflammation by pathology (such as this patient) have negative results. CT-PET imaging sensitivity and specificity for clinically diagnosed large vessel vasculitis in one retrospective study with 100 patients was 60% and 80%, respectively.12

Treatment

Initial treatment for giant cell aortitis is prednisone 40-60 mg daily. American Collegeof Cardiology/American Heart Association 2022 Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease in alignment with 2018 European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology recommend adjunctive tocilizumab, for giant cell aortitis and/or large branch vessel involvement.13,14 Tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 receptor inhibitor, is a subcutaneous weekly medication administered by the patient. Tocilizumab has been shown to reduce recurrences in 1-2 years compared to prednisone taper alone.15,16 If tocilizumab is not available, methotrexate can be used as the alternative steroid-sparing agent.

Antiplatelet or anticoagulant treatment is not routinely recommended for giant cell aortitis, however transient ischemic attack/stroke or coronary artery disease conditions would merit appropriate treatment.13

Surveillance

For giant cell aortitis in remission,2022 ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis of and Management of Aortic Disease support longitudinal aorta surveillance; annual aorta imaging by CT, MRI, or FDG-PET is reasonable as a class IIa recommendation.13

Future Study

Future study of newer nuclear radiotracers can be considered to improve detection rates of subclinical inflammation. With regards to treatment, longer duration studies with tocizolumab are needed to assess if it is useful to prevent longterm relapses and to determine optimal treatment duration.

Take Home Messages

-

Giant cell aortitis has variable presentations, which range from few or no clinical symptoms to stroke, aortic aneurysm, or aortic dissection.

-

Giant cell aortitis typically clinically warrants a longer course of immunomodulator treatment than giant cell arteritis and dedicated surveillance for longterm potential aorta complications.

Consent

The patient provided written informed consent for publication of this case report, images, and videos.

_and_corresponding_aortic_regurgitation.png)

_and_corresponding_aortic_regurgitation.png)