Introduction

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) is a small-vessel vasculitis characterized by neutrophilic infiltration and fibrinoid necrosis of postcapillary venules, clinically presenting as palpable purpura or erythematous skin lesions.1 Its causes are heterogeneous, including infections, autoimmune disorders, medications, and underlying malignancies.2,3 In oncology, drug-induced vasculitis is more frequently encountered, particularly with agents such as gemcitabine, taxanes, and platinum compounds.4–6

Malignancy-associated vasculitis represents a much rarer subset, more often described in hematological malignancies than in solid tumors.7,8 Among solid cancers, associations have been sporadically reported with lung, colorectal, and breast carcinoma, while reports involving ovarian carcinoma are exceedingly rare.9,10

Such cases raise important diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, particularly in patients with advanced disease or in palliative care settings, where the clinical objective often shifts from establishing an exact diagnosis to ensuring comfort and quality of life.5,11

We present the case of a woman with end-stage ovarian carcinoma who developed vasculitic skin lesions during hospitalization for acute renal failure. This case is remarkable not only because of the exceptional association between ovarian cancer and LCV, but also because it occurred in a palliative context, where clinical decisions were guided by comfort-focused rather than invasive approaches.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman with a medical history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus was diagnosed in 2017 with advanced high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, FIGO stage IIIC. She underwent initial debulking surgery followed by six cycles of carboplatin–paclitaxel combination chemotherapy, achieving partial response.

In 2019, she experienced her first relapse and received a second-line carboplatin–gemcitabine regimen, which provided disease control for 10 months. A subsequent relapse in 2020 was treated with weekly paclitaxel, followed by pegylated liposomal doxorubicin as fourth-line therapy in 2021. Despite these treatments, her disease continued to progress with peritoneal carcinomatosis and bilateral pleural effusion. By early 2022, given her declining performance status (ECOG 3), she was transitioned to exclusive palliative care.

She was admitted to the Department of Medical Oncology in March 2022 for acute renal failure related to progressive disease. Approximately four weeks after her last dose of liposomal doxorubicin, she developed painful erythematous and purpuric lesions on both lower extremities (Figure 1). The lesions were confluent, symmetrically distributed in dependent areas, and associated with a burning pain rated 7/10 on the visual analog scale (VAS). There was no ulceration, necrosis, or mucosal involvement.

The skin lesions caused significant discomfort, impairing ambulation and limiting her ability to perform basic daily activities. Laboratory investigations confirmed acute kidney injury but were otherwise unremarkable. Infectious and autoimmune serologies were negative. Given her frailty and end-stage status, a skin biopsy was deliberately not performed, in order to avoid additional burden and to respect the palliative goal of care. The eruption was therefore considered most likely a paraneoplastic manifestation rather than drug-induced, given the absence of recent chemotherapy changes.

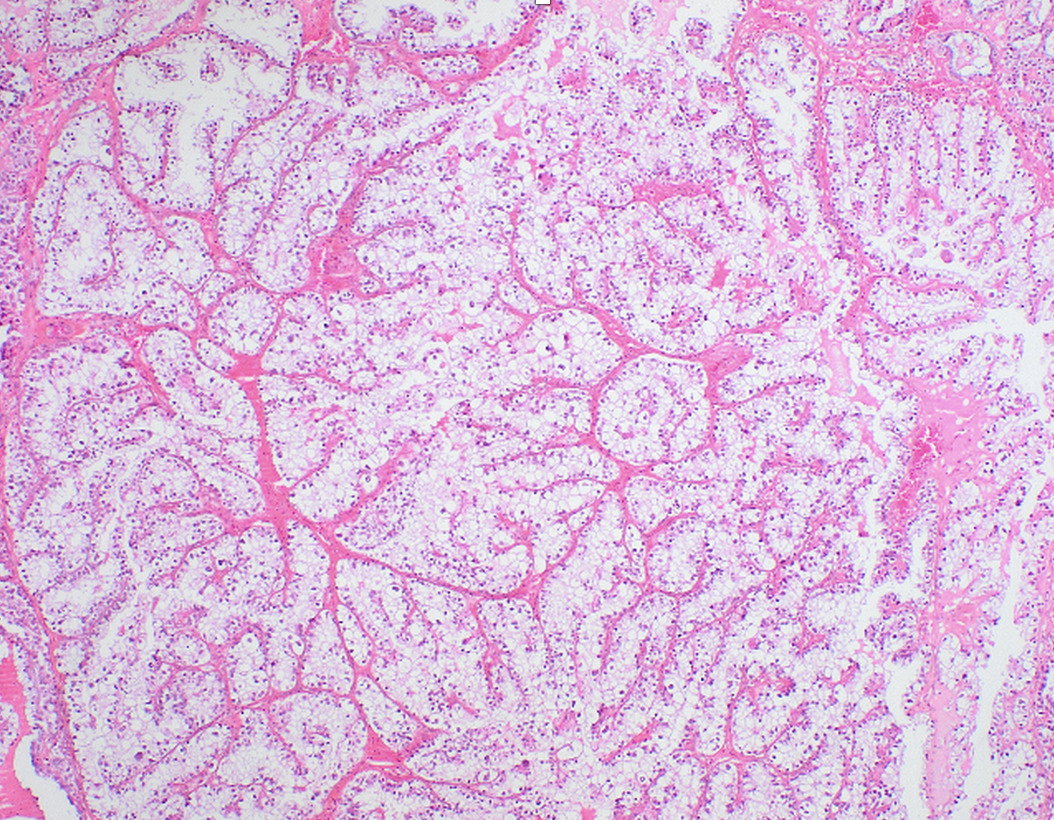

Histopathological review of her ovarian carcinoma had previously confirmed complex glandular proliferation consistent with high-grade serous carcinoma (Figure 2).

She was managed symptomatically with local skin care, emollients, and opioid-based analgesia using patient-controlled morphine analgesia (PCA), which reduced her pain from 7/10 to 3/10 (VAS). In the last week of life, due to worsening dyspnea and agitation, she required continuous subcutaneous infusion of midazolam (Hypnovel®) for palliative sedation, which provided additional comfort. Systemic corticosteroids were not initiated in accordance with her palliative goals of care. The lesions remained stable but did not regress.

Her overall condition progressively deteriorated, and she died peacefully, surrounded by her family. A chronological summary of treatments and disease evolution is presented in Table 1.

Discussion

eukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) typically presents as palpable purpura of the lower extremities. While its etiologies are diverse, paraneoplastic vasculitis remains an uncommon entity, more frequently associated with hematological malignancies than with solid tumors.1–3,7,8 In solid cancers, sporadic cases have been reported in lung, colorectal, and breast carcinoma, while associations with ovarian cancer are exceptional.9,10 To our knowledge, only very few cases of paraneoplastic LCV have been reported in ovarian carcinoma, which makes this observation particularly noteworthy.

Table 2 summarizes previously reported cases of paraneoplastic LCV in solid tumors, including gynecological cancers. This comparison highlights the uniqueness of our patient, in whom the diagnosis was made clinically in a palliative context without biopsy, with management focused exclusively on comfort.

In oncology, drug-induced vasculitis is a more frequent concern. Several chemotherapeutic agents, including gemcitabine, taxanes, platinum compounds, and capecitabine, have been implicated.4–6 In our case, the absence of recent initiation of new cytotoxic drugs, combined with the negative infectious and autoimmune workup, supports a paraneoplastic rather than drug-induced etiology.

The pathogenesis of paraneoplastic vasculitis is incompletely understood. Proposed mechanisms include immune complex deposition, tumor antigen–antibody interactions, and cytokine-mediated endothelial injury.2,7,8 Solans-Laqué et al. described a series of 15 patients with solid tumors and vasculitis, suggesting that paraneoplastic vasculitis may precede, coincide with, or follow the diagnosis of malignancy.7 Similarly, Podjasek et al. reported cutaneous LCV associated with solid tumors, including gastrointestinal and breast cancers, and emphasized the need to consider underlying malignancy in unexplained vasculitis.9

Only very limited reports have described LCV in association with gynecological malignancies. In most of those cases, the patients were treated at earlier stages of their disease, and histological confirmation of vasculitis could be obtained. Unlike previously reported gynecologic cases, our patient was in an end-stage palliative context, where declining performance status and end-of-life priorities shaped clinical decision-making. This distinction highlights the originality of our report: the diagnosis relied primarily on clinical findings, and management was deliberately oriented toward symptom control and comfort rather than exhaustive investigations or immunosuppressive therapy.

Diagnostic confirmation ideally relies on histopathological examination. In our patient, however, a biopsy was not performed due to her advanced oncologic and palliative status. We believe this decision was appropriate: a biopsy would not have altered management, would have exposed the patient to unnecessary discomfort, and would have conflicted with the palliative objective of respecting dignity and comfort.\ This illustrates a common dilemma in palliative oncology: balancing diagnostic certainty against the invasiveness and potential burden of procedures. Prior studies have shown that in patients with limited prognosis, management should prioritize comfort and avoid unnecessary investigations.5,11

Therapeutic strategies for LCV depend on the underlying etiology and clinical context. In potentially reversible cases, discontinuation of the offending drug or systemic corticosteroid therapy can be effective.4–6 Conversely, in end-of-life situations, aggressive interventions may not be justified. In our patient, symptomatic management prioritized comfort over invasive procedures. Pain was controlled with patient-controlled morphine analgesia, and in the final week of life, palliative sedation with subcutaneous midazolam was initiated to address refractory dyspnea and agitation. Palliative sedation, when used appropriately, is an ethically accepted practice in advanced cancer care and has been shown to relieve intractable symptoms while preserving dignity at the end of life.12,13

Although palliative sedation with midazolam is internationally recommended for the management of refractory symptoms at the end of life,12,13 access to this medication may be limited in resource-constrained settings. In such contexts, alternative agents such as haloperidol, chlorpromazine, or benzodiazepines are sometimes used, reflecting disparities in drug availability rather than ethical or religious prohibitions. This highlights the need to strengthen palliative care infrastructures to ensure equitable access to essential medications for symptom relief.

This case illustrates the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of vasculitic eruptions in advanced ovarian cancer. It underscores the importance for oncologists and palliative care teams to recognize such cutaneous manifestations, not to embark on exhaustive investigations, but rather to ensure that care strategies remain aligned with patient comfort and quality of life.

Conclusion

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is an exceptionally rare manifestation in patients with ovarian cancer. This case underscores the importance of recognizing paraneoplastic vasculitic eruptions in oncology, even when they arise in end-stage disease. Unlike previously reported cases, our observation occurred in a palliative context, where diagnostic certainty was less relevant than symptom relief and quality of life.

In this setting, we fully agree with the management approach that prioritized comfort and avoided unnecessary invasive procedures. Performing a skin biopsy would not have changed the therapeutic strategy and would have added burden to a frail patient; respecting her dignity and preferences was paramount.

Clinical decision-making should therefore remain guided by the principles of comfort, dignity, and individualized care. This report highlights the need to raise awareness among oncologists and palliative care teams regarding such unusual cutaneous manifestations, ensuring that management strategies remain aligned with the patient’s overall goals of care.

Patient Consent

Written informed consent for publication of this case report and the accompanying clinical images was obtained from the patient’s next of kin.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient’s family for their trust and cooperation. We also acknowledge the medical and nursing staff for their dedication in patient care.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this work.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Statement

This report describes a single patient case. According to institutional policies, ethics committee approval was not required. Patient confidentiality was maintained throughout.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.