Introduction

A pseudoaneurysm or false aneurysm is defined as a vascular lesion that results from a disruption of the tunica intima and tunica media while the tunica adventitia remains intact. True aneurysms, on the other hand, involve all three layers of the arterial wall.1–3

Pseudoaneurysms have a high risk of rupture and hemorrhage due to the disruption of vessel wall support. Superficial temporal artery (STA) pseudoaneurysms are rare lesions, but clinicians should still be cognizant of its presentation as timely diagnosis and treatment are critical. 75% to 95% STA pseudoaneurysms result from blunt trauma, while the remaining etiologies include iatrogenic causes or penetrating injury.1,2 STA pseudoaneurysm generally presents as an expansible, pulsatile, and/or indolent mass that may be associated with headaches, neurologic symptoms due to cranial nerve VII compression (dizziness, facial pain, ear discomfort, or facial droop), and occasional bruits auscultated over the temporal region.2

Arterial angiography is the diagnostic tool of choice for pseudoaneurysms and allows for endovascular treatment such as embolization and stent-graft placement at the time of diagnosis. Computed Tomography (CT) angiography and Magnetic Resonance (MR) angiography may also be used but have lower sensitivity than conventional arterial angiography.3 Noninvasive diagnostic methods include duplex ultrasonography which can demonstrate turbulent flow and vessel dilation related to the pseudoaneurysm.1,3 Needle aspiration should be avoided due to the risk of hemorrhage.1

The main treatment option for STA pseudoaneurysms is surgical resection, but embolization with IR is an emerging means of treatment. Moreover, most STA pseudoaneurysms secondary to blunt trauma are solitary.4 Here, we present a case of multiple STA pseudoaneurysms that were treated initially via glue embolization with IR but ultimately needed surgical resection. A literature search on STA pseudoaneurysms’ pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment was also performed.

Case Presentation

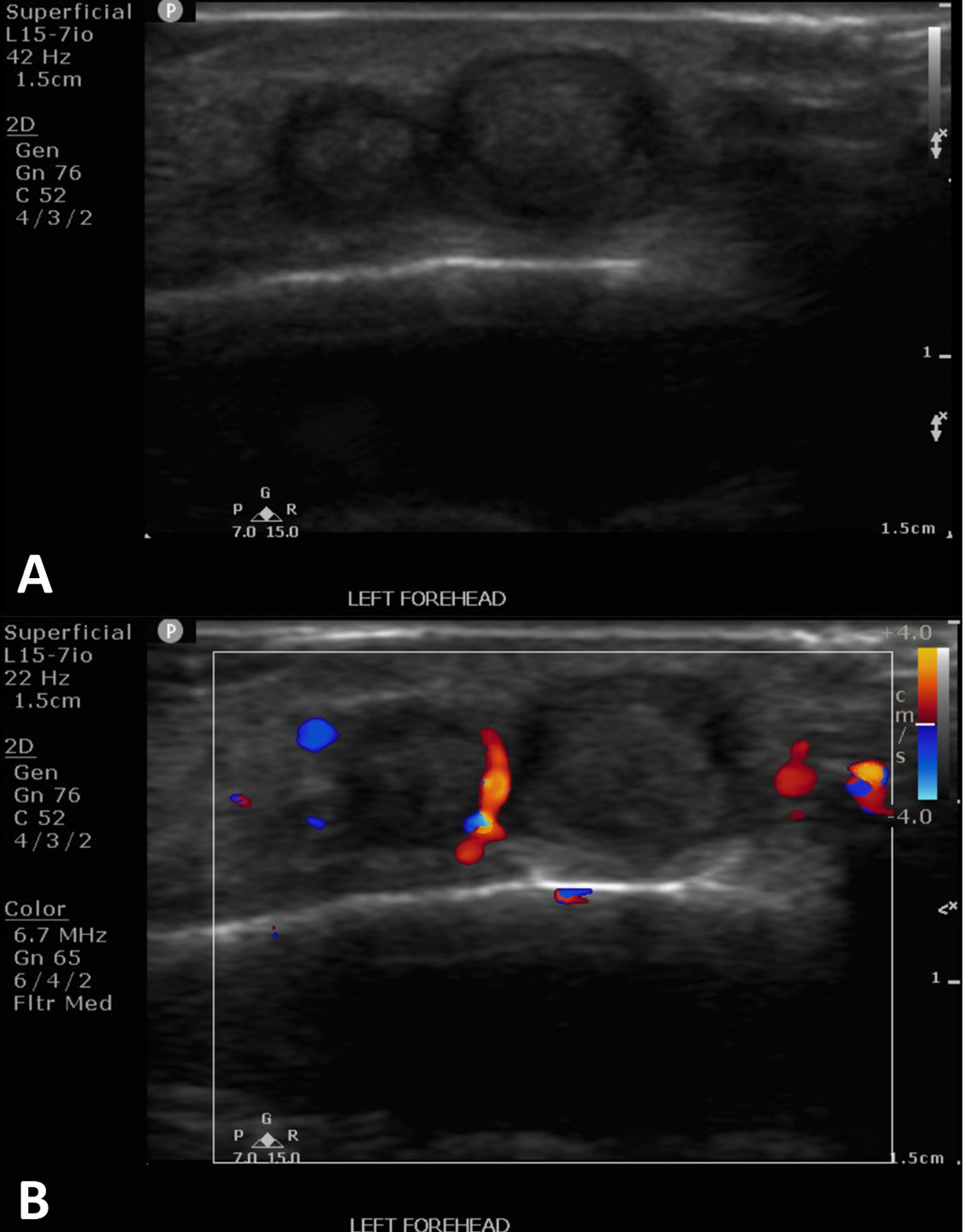

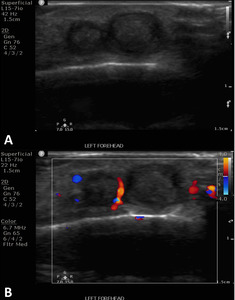

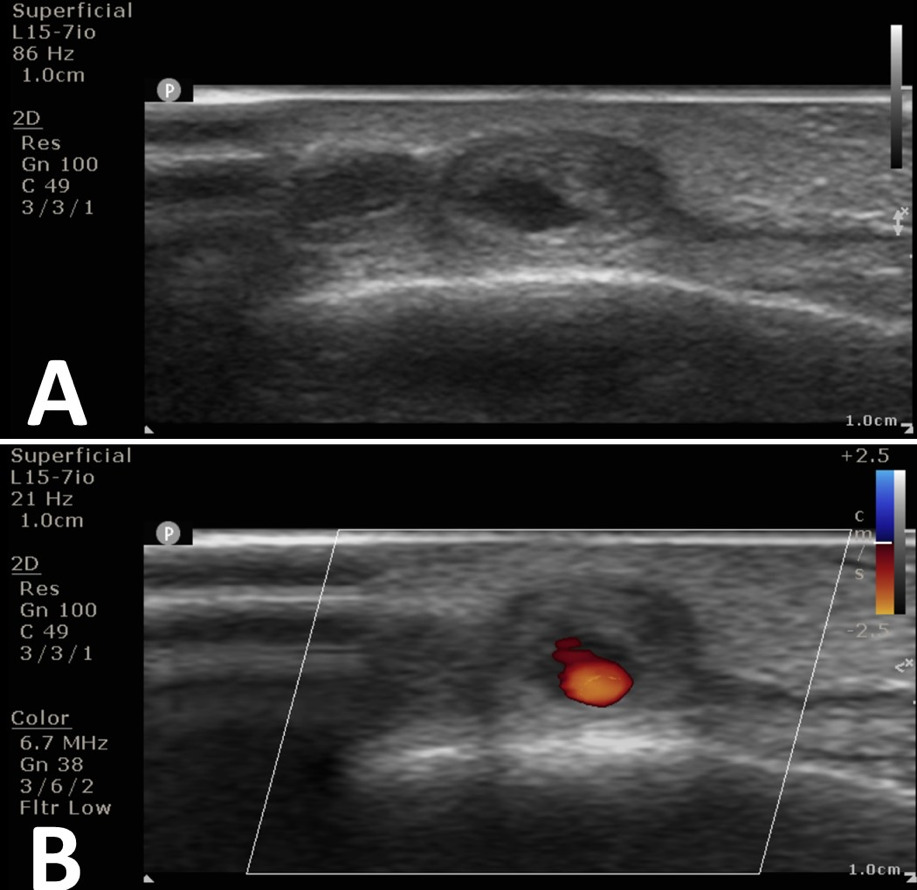

The patient is a 25-year-old male who was struck by a paintball in the left frontotemporal region, initially causing bleeding and ecchymosis. Two months later, he presented to an outpatient vascular clinic due to the development of a pulsatile mass of the left forehead (Figure 1). The clinical finding prompted a diagnostic US including arterial duplex evaluation of the site which confirmed tandem pseudoaneurysms in the scalp left of midline arising from the parent left superficial temporal artery (Figure 2).

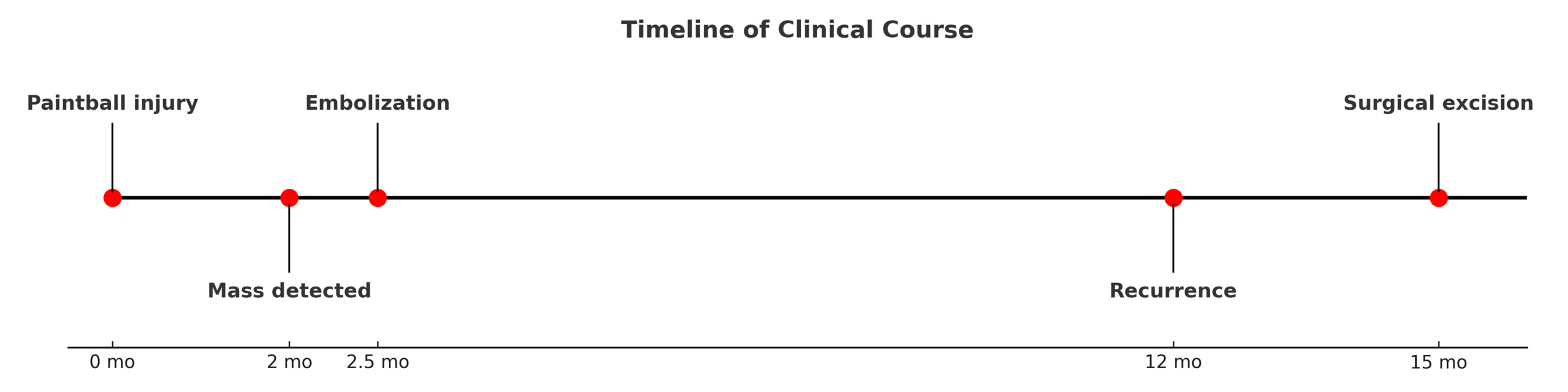

After discussion and counseling regarding the treatment options, the patient elected to have the percutaneous procedure performed in lieu of surgery as his initial choice of treatment. The patient emphasized understanding that a surgical excision may be required in the future for complete cosmetic and symptomatic resolution. Two weeks after the ultrasound study was conducted, the pseudoaneurysms were treated with direct, percutaneous pseudoaneurysm needle access and subsequent angiogram and n-BCA glue embolization. Specific procedure details include: the procedure was performed under moderate sedation with IV administration of midazolam and fentanyl. The forehead was prepped and draped in sterile fashion and subcutaneous injection of 1% lidocaine was used for local anesthesia. Then, the pseudoaneurysm was percutaneously accessed with a 21-gauge needle under direct US guidance. Angiography through the needle demonstrated successful access to the pseudoaneurysm; which was located at a branch point of the STA. Further angiographic opacification of the vascular territory demonstrated two additional small pseuaneurysms, one arising from each branch (Figure 3).

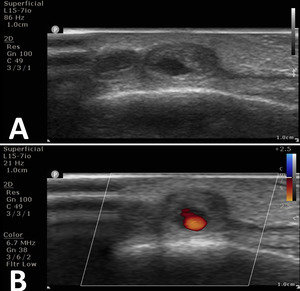

There was normal venous drainage on the scalp and no evidence of intracranial communication. Embolization with n-BCA glue was then delivered under fluoroscopic guidance. The glue embolized all three pseudoaneurysms including a short segment of the parent inflow artery and short segments of the outflow arteries. The glue cast was well visualized on fluoroscopy. Post-intervention ultrasound confirmed thrombosis of the pseudoaneurysms (Figure 4). The patient tolerated the procedure well without complications.

Unfortunately, one year later, embolization did not completely resolve the pseudoaneurysms as his lesions continued to undulate in size. He also experienced left-sided temporal headaches. Ultimately, he underwent excision of the remnant pseudoaneurysms with plastic surgery. A brief timeline of the case presentation is presented in Figure 5.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the procedure which also included the ability to publish accompanying images from the procedure. This study was conducted in accordance with relevant ethical guidelines and institutional policies regarding case reports.

Discussion

STA pseudoaneurysms are rare lesions. The first reported case of STA pseudoaneurysm secondary to blunt trauma was in 1740 by Thomas Bartholin which was treated by opening the mass and applying direct pressure.4,5 The STA, a terminal branch of the external carotid, is vulnerable to blunt head trauma due to its superficial course over the frontal bone, running within the temporoparietal fascia.1,6 Most pseudoaneurysms of the STA, especially due to blunt trauma, are solitary. Multiple pseudoaneurysms of the STA have mainly been reported as a complication resulting from craniotomy.7 Our patient’s case is unique in its presentation of multiple pseudoaneurysms secondary to blunt trauma with a paintball.

Patients often present two to six weeks after injury which is attributed to the slow expansion of the vascular lesion from the pressure of local blood flow.1 Differential diagnoses of a mass overlying the temporal region include but are not limited to lipoma, cyst, simple hematoma, abscess, inflamed lymph node, arteriovenous fistula (AVF), meningocele, encephalocele, and angiofibroma.1 Vascular inflow and outflow differentiate a pseudoaneurysm from a hematoma. While a hematoma does not have vascular inflow and outflow, a pseudoaneurysm presents with a communicating vessel to the main artery, allowing blood flow in and out of the pseudoaneurysm.6 Furthermore, a pseudoaneurysm is an extra-arterial lesion that remains connected to the arterial lumen, associated with pulsations and thrills related to systole. Imaging studies are necessary to differentiate between the vascular and nonvascular pathologies and ensure proper treatment.

Treatment generally consists of surgical resection. In a systematic review of 166 patients with reported STA pseudoaneurysms from 1861-2010 by van Uden et al., the primary treatment of STA pseudoaneurysms for 77% of patients was surgical resection.5 Other treatment options include manual compression, percutaneous thrombin injection, or endovascular intervention. In one case, Raskin et al. describe a patient who had spontaneous resolution of the STA pseudoaneurysm in nine months under close observation.6 Using shared decision-making, the patient presented in this case elected to have the pseudoaneurysms treated with percutaneous injection before pursuing the more invasive option of surgical resection. Counseling during the initial consultation was performed to inform the patient that despite percutaneous injection, there may be residual cosmetic deformities of raised and superficial protuberances on the skin surface which could potentially require cosmetic surgery to address. Our patient initially underwent glue embolization for his pseudoaneurysm but ultimately required surgical resection to address the remaining cosmetic deformities and his residual symptom of headaches. van Uden et al. reported 6% of patients with STA pseudoaneurysms require more than one intervention.5

Minimally invasive treatments for pseudoaneurysms such as coil embolization, thrombin injection, and glue embolization are promising due to their decreased risk of incisional complications (i.e. facial nerve palsy), infection, and scarring.5,8 On the other hand, surgical resection remains the treatment of choice due to its historically high success rate. Limitations to this case study include that is an isolated case presentation of a rare entity and phenomenon, potentially limiting the generalizability of the study. Additionally, given this patient’s young age and otherwise healthy status, outcomes may differ in diverse populations who may present with a different medical history than the patient in this case.

Conclusion

A case of traumatic superficial temporal artery pseudoaneurysms, initially treated with glue embolization and ultimately resolved with surgical excision, is reported. This case report contributes to the better characterization of the clinical features and treatment of this rare vascular lesion.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the support of Department of Interventional Radiology at VCUHealth and VCU School of Medicine.

_in.jpeg)

_in.jpeg)