Introduction

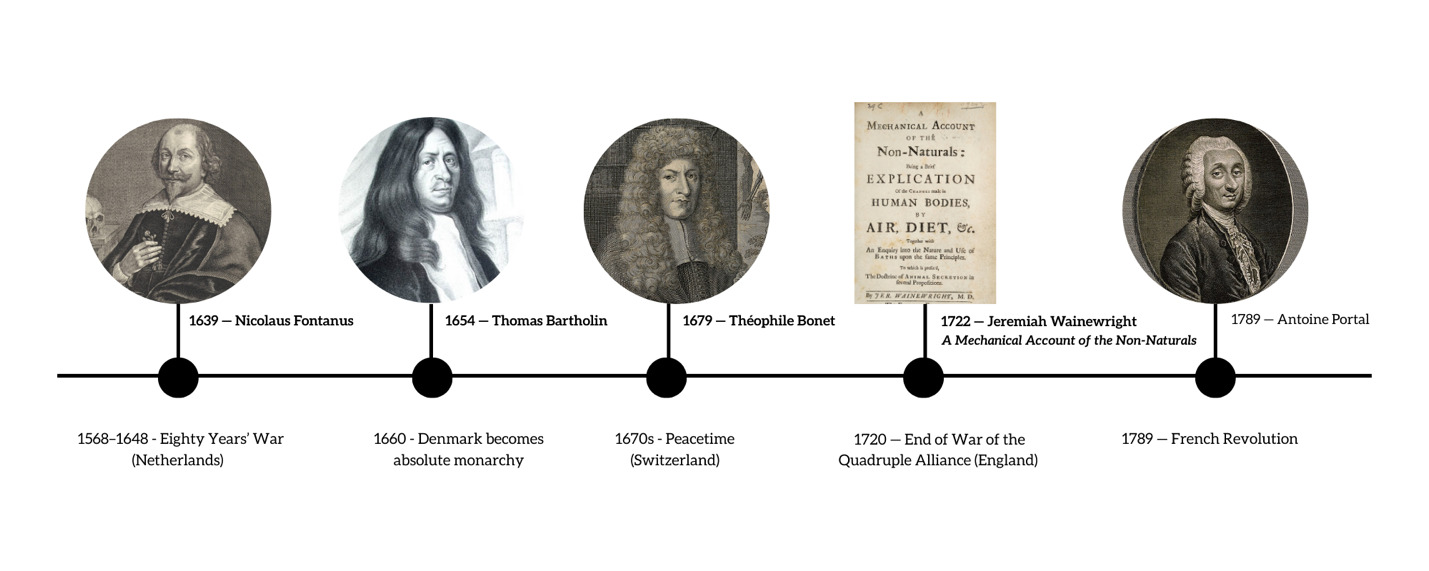

There were at least five prominent physicians that were considered to discover amyloid and amyloidosis in the 17th and 18th century.1 Among these physicians were Nicolaus Fontanus (Netherlands, 1639), Thomas Bartholin (Denmark, 1654), Théophile Bonet (Switzerland, 1679), Jeremiah Wainewright (England, 1722), and Antoine Portal (France, 1789). The selection of these physicians was based on Dr. Robert A. Kyle from the Mayo Clinic’s findings on early discoveries of amyloidosis in the first section of his publication titled “Amyloidosis: a convoluted story”.1 Situated across five different European countries, these physicians made significant advancements in amyloidosis and amyloid-related diseases, in some cases during periods of political turmoil. If the timing of their advancements had been several years earlier, there could have been different results or no results at all. Medical advances in amyloidosis and amyloid-related diseases during the 17th and 18th centuries were significantly influenced by the prevailing political climates. While stability in some states allowed discoveries to advance, turmoil in others slowed or redirected progress, shaping what discoveries in amyloidosis were made, the timing of their recognition, and which physicians ultimately received credit.

Nicolaus Fontanus (1639)

Even though the States General acted as the central government of Holland in the Hague, the seven provinces were fully autonomous, each with its own government. The Netherlands’ decentralized government, unlike the absolute monarchies in other parts of Europe, fostered a greater freedom of thought and inquiry in its individual provinces and cities. In 1639, the Dutch Republic had a decentralized bureaucratic structure. It was considered a confederal republic with seven loose confederation states. The Netherlands was still at war with Spain. Even though the Netherlands became independent in 1581, they weren’t fully recognized as independent until 1648 during the Peace of Westphalia, which ended the 80-year war. In the mid-1600s, new science made its way to the Dutch republic, including Carolus Clusius, botanist and Leiden professor, as well as Rene Descartes, French philosopher, mathematician, and scientist. However, according to Van Berkel (2010), Harold Cook’s Matters of Exchange states that "the disciplines that really count are medicine, botany, and other branches of natural history. According to him, these were indeed the disciplines that really mattered in the seventeenth century. Mathematics and physics were much more peripheral to early seventeenth century culture than we are inclined to think.2

In that year, a Dutch physician and poet named Nicolaus Fontanus was known for discovering amyloidosis. According to Harrison, Cohen, and Bulvik (2021), Fontanus completed an autopsy of a young man and found bleeding in the nasal passages (epistaxis), jaundice, and an accumulation of fluid in the abdomen (ascites). Fontanus also encountered pathological findings in the man’s liver and spleen.3 Krystal, Ross, and Mecca (2021) explained that Fontanus found sizable white masses in the spleen that were solid and stone-like. Although Fontanus did not use the explicit terminology, this may have been the first historical documentation of a sago spleen due to amyloidosis.4,5

Thomas Bartholin (1654)

Thomas Bartholin was a professor at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1654 when he published his Historiarum Anatomicarum Rariorum, which included his discovery of the human lymphatic system. Bartholin also wrote about his pathologic findings in a woman he had autopsied, including an almost impenetrably hard spleen that made a strange sound when dissected akin to cutting “spongy timbers”.5

In 1654, Denmark was ruled by King Frederick III. Although an absolute monarchy was officially established in 1660 during the Dano-Swedish war, the year 1654 marked a growing trend toward a more centralized government (Aarhus University). Denmark was considered an elective monarchy at the time, meaning that King Frederick III was elected by Council of Nobles. Bartholin was able to practice medicine and release his findings before 1672, when doctors were regulated by legislation at the request of the king and the medical field attempted to be regulated under a growing bureaucratic framework.6

Théophile Bonet (1679)

In 1652, Bonet became a member of a governing body in Geneva called the Council of Two Hundred. He was part of the legislative authority, which included Geneva, which was independent at the time, as well as Zurich, Bern, Fribourg, and Basel.7 In the 1670s, Switzerland had thirteen sovereign cantons (associated territories), known as the Old Swiss Confederacy. Citizens of Switzerland had varying amounts of freedom. Switzerland had a loose confederation of self-governing states.8

By 1679, Théophile Bonet had published the findings of Fontanus, Bartholin, and others in his work titled Sepulchretum sive Anatomia Practica. This compilation includes 3,000 autopsy reports spread across 1,700 pages and is organized by anatomical regions of the body, such as the abdomen, thorax, and head. Bonet’s Sepulchretum serves as a testament to the medical knowledge he acquired throughout his life and references a variety of notable authors, including Hippocrates, both from before and during his lifetime.1

Jeremiah Wainewright (1722)

Jeremiah Wainewright was influenced by Sir Isaac Newton, who wrote A Mechanical Account of the Non-Naturals in 1707, that “all the Philosophy that has yet appear’d in the World, is no better than Trifling Romance, except what hath been writ by the famous Sir Isaac Newton, and some few others, who have built their Philosophical Reasonings upon Mathematical Principles.” Speculative approaches were contrasted to Newton’s mathematical approaches at the time by several physicians, including Wainewright.9

During this time, the British Empire was growing, and the government was a constitutional monarchy. Physicians were considered to be at the top of the hierarchy. In 1722, Wainewright was a member of the College of Physicians in London.10 In the same year, Wainewright documented his pathological findings from the autopsy of a patient he suspected had thyroid disease due to an edematous neck. To his surprise, the post-mortem examination revealed a striking hepatomegaly. The patient’s liver was enlarged to two to three times its normal size and was infiltrated with a viscous and pale gelatinous material.11

Antoine Portal (1789)

Portal made a significant breakthrough in Amyloidosis, the same year that the French Revolution occurred. Before the French revolution, France was governed by an absolute monarchy, then moved to an Estates-General before creating a National Assembly in 1789. A new National Constituent Assembly was being assembled in France. France became a constitutional monarchy in 1789.12

The French Revolution had little impact on the career of Antoine Portal, a prominent French anatomist and medical historian. He continued his work teaching at the Collège de France and the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle. His career thrived throughout the revolutionary period and beyond, as he was appointed to the Institut de France in 1795 and worked for many more years (Busquet, 1928). In 1818, he became the first physician to King Louis XVIII, despite his old age. He kept this position under Charles X, who also made him a baron. Finally, after numerous appeals from Portal, the Académie Royal de Médecine was established in 1820, and he was named its permanent honorary president.13

In 1789, Antoine Portal described a liver in an older woman that resembled lard (lardaceous). This description was likely the first of its kind and has since become standard in the vocabulary used by physicians and scientists studying amyloidosis. Additionally, Portal noted hepatomegaly in a young boy with tuberculosis. Portal also discovered that the lard-like substance in the boy’s liver became dense and solid when heated, similar to the protein albumin.1

Bureaucracies and Political Turmoil

Discoveries and advancements in amyloidosis and amyloid-related diseases were closely tied to the bureaucratic capacity of states and to the disruptions of war and revolution that characterized seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe. The relationship between government structures and medical discovery was never incidental. Political turmoil delayed, accelerated, or redirected reforms, shaping the institutional frameworks within which medicine advanced. Governments not only reacted to disease but also formalized medical practice through legislation, established or resisted new institutions, and transformed hospitals and schools into instruments of state power. Breakthrough discoveries in amyloidosis and related conditions therefore, occurred alongside bureaucratic evolution and political conflict, as seen in the Netherlands, Denmark, Switzerland, England, and France (see Table 1).

The Netherlands, as a republic, and Switzerland, as a loose confederation of self-governing states, supported local autonomy and intellectual inquiry but lacked centralized coordination. In Denmark, reforms were postponed until absolutism enabled the growth of centralized bureaucracies. England’s constitutional monarchy legitimized discoveries through hybrid channels that combined court, parliament, and science. In France, successive shifts from absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy, to republic, and back again underscored the profound political instability brought on by the Revolution.10

Breakthroughs in amyloidosis during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were shaped by the political environments in which they emerged (see Table 1). In the Netherlands, Fontanus’s discovery took place during the Eighty Years War, while in France, Portal’s work advanced as revolutionary change dismantled and rebuilt the medical system. By contrast, the relative stability of Switzerland and England allowed Bonet and Wainewright to legitimize and extend their work, whereas Denmark’s delayed reforms under shifting monarchies demonstrated how bureaucratic transitions could hinder progress, even though Bartholin’s findings preceded such legislation.6

Prestige within elite circles also played an influential role. Membership in professional societies or appointments to royal courts and legislative bodies gave physicians authority and protection to advance medical work despite political turmoil, safeguarding discoveries and ensuring their continuation.7,13,14 These cases highlight that medical discovery was inseparable from its political context and was shaped by the dynamics of government and conflict across Europe. The discoveries helped shape the understanding of amyloidosis and amyloid-related diseases for the 19th century, with botanist Matthias Schleiden introducing the term “amyloid” in 1838, and pathologist Rudolph Virchow’s applying the term to human disease in 1854.1

The early discoveries of amyloidosis and amyloid-related diseases show how much the broader political climate and its bureaucracies shaped medical progress. Periods of stability gave physicians the space to pursue and publish their work, while turmoil delayed or redirected progress (see Figure 1). By the nineteenth century, these dynamics connected to the professionalization of medicine, as institutions began formalizing training, regulating practice, and consolidating knowledge. Today, the same lesson holds: discoveries do not happen in isolation but depend on the capacity of states and institutions to support and sustain research.