Introduction

Ischemic stroke accounts for 87% of all strokes globally and occurs when blood flow to the brain is obstructed resulting in tissue damage.1 In the United States, nearly 800,000 people are affected annually.2 Risk factors include age, gender, race, and pre-existing conditions such as heart disease, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, obesity, sickle cell disease, and chronic kidney disease.3

The right medial temporal lobe is critical for long-term memory formation, while the right occipital lobe primarily processes visual stimuli. Ischemic strokes in these regions, though less common, pose significant clinical complexities due to their specialized functions.4,5 Approximately 20% of strokes involve the posterior circulation that supplies these areas.6 Key risk factors include hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, smoking, atrial fibrillation, genetic predisposition, physical inactivity, and prior transient ischemic attacks (TIAs).7 Temporal lobe strokes often cause memory loss, confusion, and spatial disorientation,8 whereas occipital lobe strokes typically result in visual field deficits, such as homonymous hemianopia, visual hallucinations, or cortical blindness.9

Early recognition of symptoms and risk factors is crucial for prompt diagnosis and expedited treatment to help minimize the long-term cognitive and functional impairments associated with these strokes. We present the case of a 62-year-old male with a history of TIA arriving to the Emergency Department (ED) with left-sided weakness and chest pain persistent for ninety minutes. The patient was diagnosed with an acute ischemic stroke of the right medial temporal and right occipital lobe regions.

Case Presentation

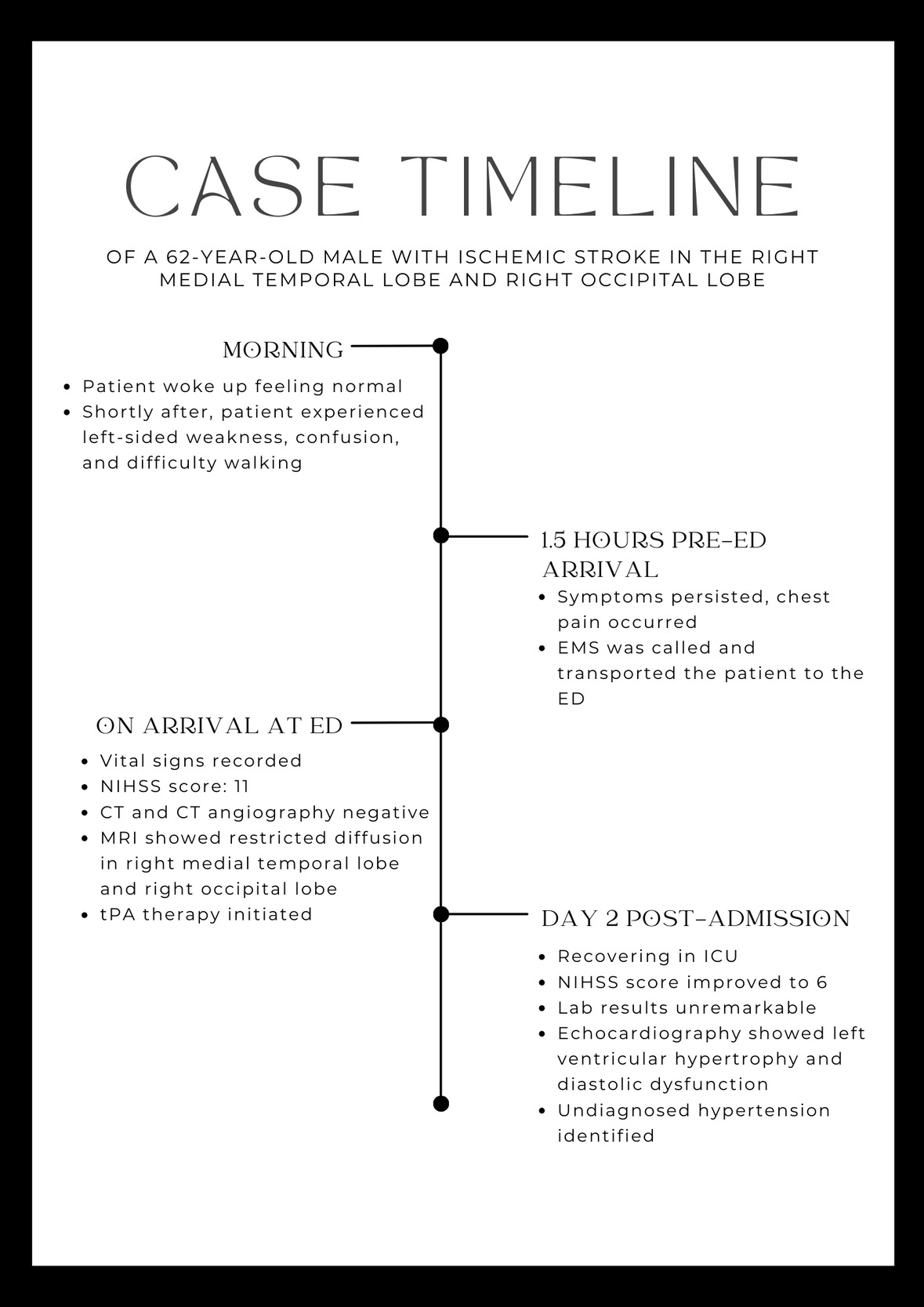

A 62-year-old African American male, with a medical history of transient ischemic attack TIA), arrived at the ED via emergency medical services (EMS). He complained of left-sided weakness. His last known normal was ninety minutes prior to arrival. The patient reported feeling normal upon waking up, but soon after, he experienced left-sided weakness, confusion, and difficulty walking. A timeline of the case is presented in Figure 1. EMS confirmed that the patient had no deficits from previous strokes and usually walks unaided except for the intermittent use of a cane for arthritis in his right knee during long walks.

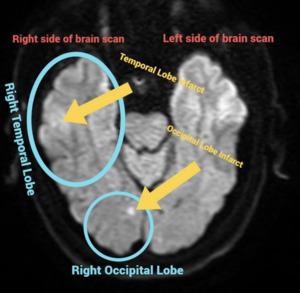

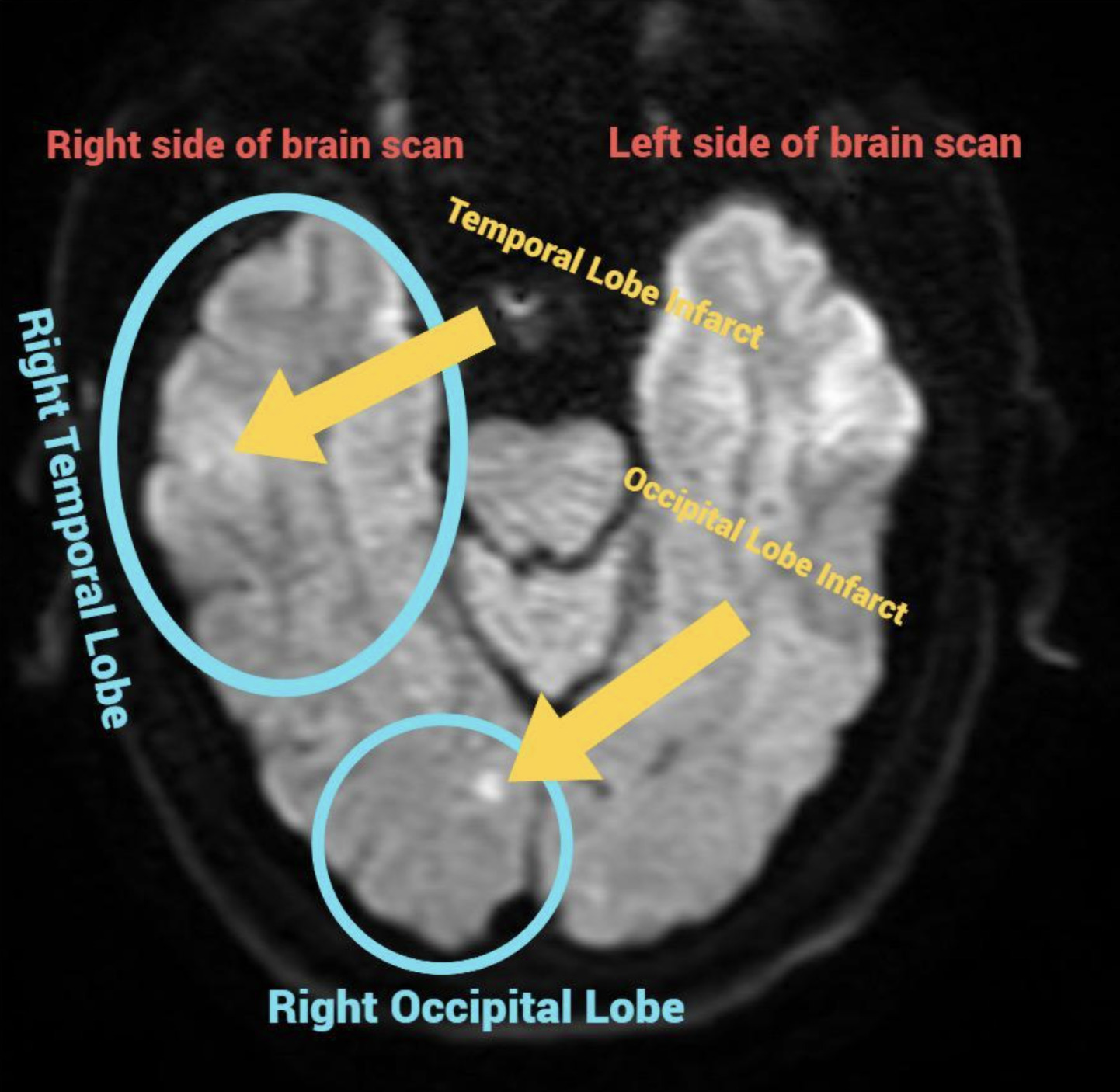

Upon his arrival to the ED, the patient had a temperature of 98.5°F, blood pressure of 180/100 mm Hg, heart rate of 72 beats per minute, and respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute. His pulse oximeter reading was 93% on room air. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was 11. The initial head computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography of the head and neck showed no hemorrhage or large vessel occlusion. The patient met the time criteria for tissue plasminogen activator administration (tPA) with no contraindications and this was initiated in the ED. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain revealed restricted diffusion in the right medial temporal lobe and right occipital lobe concerning for an acute ischemic stroke (Figure 2). The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further monitoring of his neurologic status.

On Day 2 of his ICU stay, the patient’s NIHSS score improved to 6. His laboratory results were unremarkable. An echocardiogram showed left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction. The patient was found to have the modifiable risk factor of untreated hypertension.

Discussion

This case highlights the importance of understanding the unique presentation of medial temporal and occipital lobes strokes and the need to interpret stroke presentations accurately and tailor management strategies. Strokes in these regions often affect visual deficits, memory issues, and disorientation, emphasizing the need for prompt intervention with identification of behavioral and cognitive symptoms.9,10 The patient’s symptoms of unilateral weakness, confusion, and visual disturbances were consistent with known clinical manifestations of strokes in these areas.11

The patient’s weakness and difficulty with ambulation primarily reflect disruption of the corticospinal tracts, with further impairment likely due to ischemia in the medial temporal and occipital lobes. Right medial temporal lobe ischemia likely impaired the encoding and processing of spatial and contextual information, leading to confusion and disorientation. Occipital lobe dysfunction may have contributed to subtle visual field deficits or difficulty integrating visual information. Combined with temporal lobe dysfunction, these factors could explain the patient’s reported difficulty with ambulation. Table 1 shows symptoms for each of these regions of the brain to help aid in recognition.

This case highlights the limitations of CT in detecting early ischemic changes. MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) plays a vital role in identifying ischemic changes, particularly when initial CT scan is read as unremarkable. This underscores the critical role of early advanced imaging in the assessment of stroke.

Effective case management included rapid recognition of stroke symptoms and timely administration of tPA, consistent with best practices for acute ischemic stroke management.1,12 For this patient, the MRI confirmed the infarct locations, and the patient’s partial recovery as indicated by the decrease in NIHSS from 11 to 6 following tPA administration demonstrates the efficacy of early interventions such as thrombolysis.13,14

This case is particularly relevant for emergency physicians as it shows the importance of recognizing specific stroke presentations involving specialized brain regions, such as the medial temporal and occipital lobes. High suspicion for these types of strokes should be considered with clinical presentations involving visual and cognitive deficits. The case also highlights the critical role of rapid imaging, early identification of risk factors, and prompt initiation of thrombolytic therapy to optimize patient outcomes.

An area for potential improvement was the patient’s untreated hypertension, a well-established risk factor for both initial and recurrent strokes. This aspect highlights the need to address modifiable risk factors during and after acute stroke care for prevention of recurrence.15

Future strategies should prioritize managing modifiable risk factors such as hypertension, educating patients on early recognition of stroke symptoms, and increasing access to advanced imaging for suspected stroke cases to ensure timely and accurate diagnoses. Further research is necessary to explore the long-term outcomes of strokes affecting the right medial temporal and occipital lobes, aiding in the development of targeted rehabilitation interventions.

Physicians should be vigilant for symptoms such as confusion and disorientation in cases of right medial temporal lobe ischemia, recognizing its role in spatial navigation, memory, and emotional processing. Additionally, subtle visual field deficits and visuospatial processing issues should be assessed with suspicion of occipital lobe ischemia, even in the absence of overt neglect.

Conclusion

The case study underscores the importance of early detection and treatment of ischemic strokes. The emergency department, in collaboration with neurology, have instituted best practices and time sensitive targets in order to ensure expedited care. Primary and secondary stroke prevention continues to focus on controlling modifiable risk factors.

Ethical considerations

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.