INTRODUCTION

The operating theatre is a high-pressure high-performance environment requiring a combination of focus, decision making, technical and non-technical skills to optimise patient care. Surgeons may undergo a significant “stress response” – a psychological, physiological, and biochemical state of hyper-arousal, regulated by the sympathetic nervous system. Activated when perceived demands of a situation exceed the perceived resources, this response is characterised by a predictable and replicable set of psychological and physiological variations, such as increased heart rate, decreased heart rate variability, raised salivary cortisol, and increased self-reported stress and anxiety.

The negative impact of stress response activation on cognition, memory, technical skills and decision making is well described within healthcare practitioners and surgeons. The association between increased stress and poor patient outcomes, demonstrated across healthcare, is reflected in the Yerkes-Dodson law describing the relationship between hyper-arousal and performance.1 This highlights a key area for improved surgical care, where optimal human factors- communication, leadership and psychological safety- are fundamental for integrating complex individual, technical and organisational factors in the operating theatre.2

Training individuals to perform optimally in stressful environments has been extensively studied in psychology and applied to high-performance industries such as aviation and the military. Stress Inoculation Training, initially developed as a clinical intervention for individuals suffering with stress-related psychopathology, consists of three-phase cognitive behavioural skills teaching and graduated exposure to stressors in a controlled environment.3

Stress Exposure Training (SET) builds on this by using the same principles to inoculate individuals against the psychological and physiological impacts of acute stress, facilitating optimal performance.4

This framework has three phases. In the “Education” phase, individuals learn about the stress response and its impact on performance.5 In the “Skills Acquisition” phase, individuals develop psychological and technical competencies. Key psychological skills—such as mental rehearsal, breathing techniques, and awareness of maladaptive thoughts, along with strategies to manage them—form the foundation of this approach.6

Technical skills acquisition is task-specific, ranging from warfare decision making to athletic performance. Finally, the “Application and Practice” phase consolidates these skills and individuals begin to apply them under increasingly stressful environmental conditions.3,4 Crucially, the intensity of environmental stressors or complexity of task at hand is only increased once the trainee has proficiently completed the assigned task under the current level. This process is vital to facilitate skill-acquisition and prevent overwhelm and associated negative impact on confidence and progression.7

Military divisions have effectively employed iterations of this training, both as dedicated programmes and within existing courses. “Mindfulness Based Mind Fitness Training” and “General Mental Skills Training” have been implemented during Marine Training8–10 with the infamous Navy SEAL training being the most extreme example.

SET has also been used within aerospace and aviation, where junior pilots have been exposure to environmental stressors, such as decreased vision or cold temperatures, combined with cognitive skills training. These have shown “SET-trained” individuals to outperform “traditionally trained” peers in performance-based outcomes.11,12

SET has been trialled in an extremely limited manner in healthcare, and even less so in surgery. Yet, the importance of stress response management is becoming increasingly evident despite the limited training and resources available. This systematic review considers the current literature on SET, its applications in high-stress, high-performance industries and existing models of SET in healthcare and surgery, to inform and develop a stress exposure training programme to address this deficit.

METHODS

This systematic review was performed in keeping with the PRISMA guidelines.13 This review is based on previous study results and so no ethical approval, or consent was required.

Search

PubMed, Ovid and Scopus were interrogated without limit on time period with the following search strategy: Both Title/Abstract and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) were utilised (where available) for article identification. Authors AW and CL independently performed title and abstract screening and for all identified articles, followed by full text review (Table 1) for those meeting the inclusion criteria below. In addition, a manual search of identified reviews and referencing was performed to identify any additional relevant studies. Last search conducted January 2023.

(Stress response OR stress exposure OR Stress inoculation) AND (medical OR surgery OR healthcare). For each term common synonyms and MeSH headings were incorporated.

Eligibility Criteria

Article types excluded at screening were those retracted, reviews, editorials, book chapters and conference abstracts. Additionally, those clearly not in the context of training or unrelated to the subject of interest were excluded. All other articles were included.

Data collection process

Authors AW and CL performed data collection independently against an agreed criteria including relevant subgroup, study design, participant characteristics, detail of intervention and results. A subsequent round of further data collection was undertaken by author AW. No disagreements regarding study eligibility arose, however these would have been further discussed with all authors in the first instance if the need arose.

Results Reporting

Meta-analysis was not performed. Data is presented in Table 1 within three distinct subgroups: A) Simulation Training and Stress Response in Healthcare; B) Stress Response in Surgery and C) Stress Exposure Training in Healthcare.

RESULTS

Systemic review identified 1335 eligible papers, refined to 103 based on abstracts, and with 36 undergoing full text review, as detailed in PRISMA flowchart below (Figure 1) and Table 1.

These were subcategorised under the following headings:

-

Simulation Training & Stress Response within Healthcare.

-

Stress Response in Surgery; and

-

Stress Exposure Training in Healthcare.

Simulation Training & Stress Response within Healthcare

9 studies on simulation training and the stress response in healthcare workers were selected for full text review. Simulation training has been shown to elicit an equivocal stress response in high-fidelity simulations to “live” clinical duties within healthcare and surgical training.17 It is safe, reproducible, environment-controlled and cost-effective, and is invaluable in training multi-disciplinary team members in both technical and non-technical skills required for effective clinical practice.

Stecz et al. (2021) studied the stress response in medical students during anaesthetic simulation sessions. They assessed three domains to quantify the stress response in their subjects; a) physiological (oxygen saturations, blood pressure, respiratory rate); b) biochemical (salivary cortisol, testosterone IgA and alpha-amylase) and c) psychological (STAI questionnaires), demonstrating a rise across these parameters during the exercise.15 Geeraerts et al. (2017) also found raised stress scores and salivary alpha-amylase following anaesthetic themed simulation in a study of 27 residents; however, they did not demonstrate a significant correlation between stress parameters and non-technical performance ^.14 ^

Within Emergency Medicine, multiple studies have looked at the stress response in high-fidelity simulated scenarios. Ghazali et al. (2018), Schreckengaust et al. (2014) and Valentini et al. (2015) have all demonstrated increased stress levels amongst healthcare professionals during emergency simulations through various physiological, biochemical and psychological parameters, whereas Janicki et al. (2020) also demonstrated highest levels of stress associated with “live” clinical shifts amongst ED residents.16,18–20

Al-Qahtani et al. (2018) conducted a randomised control trial looking at time as an environmental stressor on doctor’s performance and found increased time pressure to be associated with poorer diagnostic accuracy, increased stress and less plausible hypotheses generated.21 However, Salzman et al. (2016) found no effect of environmental noise as a stressor on subject’s decision-making time or heart-rate variability.22

The Stress Response in Surgery

9 studies and 1 review article assessing the stress response in surgeons were identified: 5 focussing on clinical activities (including operating) and 4 on high-fidelity simulation.

Awad et al. (2022) demonstrated increased stress in cardiac surgical residents whilst operating compared to non-operative clinical work, and found stress levels were highest when operating as lead surgeon and whilst undertaking critical operative steps.23 Similarly, Gupta et al. (2012) measured the stress response in orthopaedic surgeons (three consultants and three trainees) whilst operating as lead surgeon, assistant surgeon and when operating independently. They identified increased stress levels during operative versus non-operative clinical work, highest in trainee surgeons when operating independently.24

This increased stress level demonstrated by trainee surgeons (cf. consultant surgeons) has been replicated elsewhere. Bakhsh et al (2018) measured the stress response in surgeons of varying experience during a simulated high-fidelity endovascular simulation. In a cohort of 35 participants, they demonstrated significantly increased sympathetic response amongst the junior surgeons, most marked in team-simulation compared with individual simulation. This was not replicated in the consultant surgeon group who demonstrated an equally elevated sympathetic response in both settings.25

Peri-operative stress can be categorised as (i) “patient related” (e.g. technical challenges or unexpected intra-operative findings); or (ii) “environmental” (e.g. noise levels, distractions and equipment malfunctioning). Simulated intra-operative haemorrhage has been shown to impair technical ability, communication skills and increase measured stress.25–27 Increased background theatre noise and time pressures have also been shown to increase the stress response and impair surgical performance.21,28

Stress Exposure Training in Healthcare

19 studies on stress management interventions within healthcare workers were identified, including emergency medicine, surgery and members of the wider healthcare multi-disciplinary team.14,15,17,20,29 Interventions ranged from 8-week psychological interventions, in person and remote lifestyle and wellness advice, and short “debrief” scenarios following high-stress events, with variable results.

Aronson et al. (2002) trialled cognitive behavioural therapy-style interventions in Emergency Medicine Residents undergoing simulation-based training. The intervention group received mental performance training prior to simulated patient scenarios and reported this to be valuable for their careers despite performing to a similar standard as the control group.30 Cayir et al. (2021) demonstrated an association between a contemplative practice tool (“The Pause”) and decreased stress response.31 Further mindfulness-based interventions, student led “resilience” workshops and “Mind-Body Training” have all been shown to be effective in reducing healthcare professional stress either through daily clinical activities or high-fidelity simulation.32–35

Wetzel et al (2011) developed a “Stress Management Training” programme for surgeons in which a group of 8 trainee surgeons underwent a series of psychological interventions between two simulated carotid endarterectomy procedures. The intervention consisted of written information on stress management, mental rehearsal and facilitated preparation prior to and following undergoing the simulated scenarios. The study group demonstrated significantly lower stress metrics across several variables (heart rate variability, communication skills, technical skills, and end-product completion) in the study group between the first and second simulation, with no similar improvements observed in the control group.36

Goldberg et al (2018) studied the stress response in 137 first- and second-year surgical residents, in which 65 were assigned to a “stress-management curriculum” between 2011-2016. This was designed in collaboration with a sport psychologist and consisted of educational tools and a weekly “in-person” sessions looking at the application of various stress management techniques within surgical practice. The intervention group demonstrated superior diagnostic efficiency and greater technical accuracy compared to the control group despite no statistically significant variation in measured stress markers.37

LeBares et al. (2021) conducted a randomised control trial in which the intervention group of surgical residents underwent weekly mindfulness based, in-person stress management sessions as part of their residency. They found perceived stress to remain similar in both control and intervention groups, although cognitive function and emotional exhaustion were much improved in the intervention group ^.38 ^ Similarly, Luton et al. (2021) conducted a prospective cohort study of junior surgical trainees, who underwent weekly “Enhanced Stress Resilience Training” remote tutorials over a 5-week period, reporting this programme to be effective, feasible and deliverable to a large audience.39 They subsequently trialled this on 43 students over a 2-year period, with primary endpoints of career progression (assessed by ARCP outcome 6 and obtaining a national training number), and secondary end-points of perceived stress and burnout. They reported improved career progression, perceived stress levels and reduced perception of burnout.40

“Mental Imagery Training” and “Surgical Cognitive Simulation” have also been shown to improve technical performance41,42 and repeated high-fidelity simulation sessions has been shown to decreased stress response amongst medical students in surgical specialties.43

DISCUSSION

The increased stress response demonstrated by operating surgeons is well documented in a variety of high-fidelity simulation and “live” studies, as is the potential detrimental effect on performance and ultimately patient outcomes. This systematic review identifies a large gap in surgical training and introduces the role for stress exposure training to surgery as a potential solution.

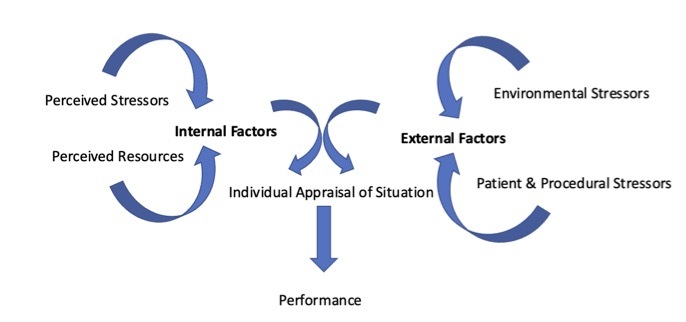

The cognitive behavioural therapy principles underpinning SET provide targets for modulation and mitigation of the stress response and subsequent negative effects, demonstrated in Figure 2. This forms the basis of “Phase 1: Education”, along with supplementary material around the stress response and impact on performance. It is amenable to remote delivery, which may be preferable considering time and financial constraints challenging trainee surgeons in the current climate.39

Wide heterogeneity in the delivery of “Phase 2: Skills Acquisition” has been demonstrated throughout the existing research. Optimal efficacy appears within four and seven skill acquisition sessions delivered regularly by individuals with lived experience of the stressors and proficient in the respective tasks.5,44 Mindfulness-based interventions reduce perceived stress and address the systemic stressors of Surgical Training (e.g. burnout, career progression) but has not yet been integrated with skills-based training to optimise performance.

“Phase 3: Application and practice” is amenable to high fidelity simulation training, providing a relevant, safe space for individuals to apply skills learned in Phase 2, within a fully controlled environment which can be manipulated to increase the stress experienced by the individual. Individuals’ stress response can be reliably demonstrated by variations in physiological and psychological parameters and accredited questionnaires (e.g. STAI). Biochemical measures such as salivary cortisol and alpha amylase have shown less predictable variations as part of the stress response, therefore offering a less reliable research tool.

Awtry et al. (2025) recently highlighted surgeons stress response as a modifiable target to improve patient outcomes, by demonstrating and association between decreased HRV in the first 5 minutes of an operation and decreased major complications in a prospective cohort study of 38 attending surgeons across 793 surgical procedures.45 Whilst increased stress was with associated decreased complication rates, this is likely due to the initial increase in arousal and performance demonstrated by Yerkes & Dobson and validated throughout high performance industries, as all participants were senior surgeons performing mostly elective procedures - therefore unlikely to experiencing an excessive stress response. The study group are also keen to highlight their data does not offer insight into the surgeon’s stress response beyond the initial 5 minutes, and subsequently their ability to manage their stress response during challenging intra-operative or environmental events. Nevertheless, this study supports the body of data demonstrating the impact of the surgeon’s stress response on patient outcomes, safe and practical methods of monitoring this and collective intra-operative data and highlighting the stress response as a modifiable target in surgical outcomes.

This review is limited by scarce literature on stress exposure training in medicine and surgery and has drawn relevant themes and results from contributing components, such as stress exposure training in alternative industries, activation of the stress response in surgeons and how this can be monitored, to formulate a working hypothesis for the next stage of this research.

CONCLUSIONS

Surgeons may undergo a significant stress response whilst operating associated with decreased technical and non-technical performance, with potential detriment to patient outcomes. This stress response is related to both external factors, such as environmental and procedural stressors, and internal factors, such as the individual’s ability to manage their perception of the situation. These findings are most acutely demonstrated amongst junior and trainee surgeons.

The need for stress management training for surgeons has been discussed widely in recent literature and has been cited as one of the fundamental areas lacking in the current surgical curriculum. The benefits are wide reaching – including scope to optimise patient outcomes and surgical performance, improved health of the individual surgeon, career longevity, reduced burnout-rates and improve workforce retention. The relationship between managing an individual’s stress response and ability to demonstrate optimal human factors skills, such as situational awareness, problem solving and communication, and technical operative skills is in inseparable, thus strengthening the importance of this work in terms of patient safety and outcomes.

This systematic review demonstrates the efficacy of SET in analogous industries and provides an evidence-based starting point for the development of a training programme addressing these deficits.

We propose a training programme where individuals undertake clinical simulations in matched to their skill level under gradually increasing environmental and procedural stressors over a 6–8-week period, augmented with stress management training throughout. Stress would be measured through physiological and psychological metrics and performance-based outcomes measured by independent observers against a pre-defined checklist.

A pilot study is in development, with each phase constructed with input from experts in medical education, surgical training, teams and individuals who have successfully implemented SET into their workplace, alongside those working in “acute” surgical care and have developed and refined their own “surgical stress management” skills throughout their careers.

We hypothesise this will enable surgical trainees to develop psychological and practical skills to perform optimally under stress and mitigate the negative impact of the stress response. We propose this programme can be generalised to meet the needs of the wider MDT including emergency and prehospital medicine and anaesthetics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

_flowchart_showing_demonstrating_the_process_from_identification_o.png)

_flowchart_showing_demonstrating_the_process_from_identification_o.png)