Introduction

Survival after liver transplantation has improved significantly over the past two decades, primarily due to advancements in immunosuppressive regimens and imaging techniques.1–3 Despite this progress, post-transplant malignancy remains a leading cause of late mortality, with incidence estimates ranging from 3.1% to 14.4% among liver transplant recipients.4 Immunosuppressive therapy, while essential to prevent graft rejection, heightens vulnerability to oncogenesis and complicates both diagnosis and management.

This case report illustrates a critical diagnostic challenge in this high-risk population: distinguishing true metastatic disease from benign hepatic lesions in the setting of known malignancy. A misdiagnosis led to unnecessary chemotherapy in a liver transplant recipient with a newly diagnosed gastric adenocarcinoma. The lesion was later reclassified as benign, enabling curative surgical intervention. We aim to highlight the importance of reevaluation, multidisciplinary input, and careful diagnostic staging in immunosuppressed patients presenting with new lesions.

Case Presentation

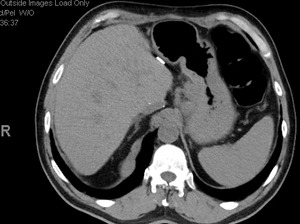

A 63-year-old liver transplant recipient, with a history of transplantation for Hepatitis C-related cirrhosis performed over a decade ago, presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain, nausea, and unintentional weight loss. CT Imaging revealed a large gastric mass and a 1.9 cm hypoattenuating lesion in the inferior right hepatic lobe (Figure 1). Endoscopy confirmed a friable, ulcerated gastric mass involving the cardia and extending into the gastroesophageal junction. Biopsies identified gastric adenocarcinoma.

Given the liver lesion and transplant history, metastatic disease was presumed. The patient was not considered a surgical candidate due to chronic immunosuppression with tacrolimus (Prograf) and perceived high surgical risk. Immunotherapy was avoided for similar reasons. Systemic chemotherapy with modified FOLFOX6 was initiated, and tacrolimus dosing was reduced to mitigate the immunosuppressive burden.

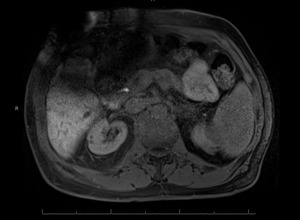

After multiple chemotherapy cycles, PET imaging demonstrated decreased metabolic activity in both the gastric and liver lesions. However, a follow-up MRI (Figure 2) raised concerns about the initial hepatic diagnosis. Multidisciplinary tumor board review led to repeat imaging and reinterpretation, ultimately revealing the lesion to be a benign liver cyst. This pivotal reassessment prompted a major shift in management.

The patient subsequently underwent curative total gastrectomy, esophagojejunostomy, and jejunostomy-tube placement. Postoperative complications included hypertensive crisis and hyperglycemia, followed by hypotension requiring return to the operating room for ligation of a bleeding vessel. The patient stabilized and was ultimately discharged home.

Discussion

This case exemplifies the complexities of diagnosing malignancy in immunosuppressed transplant recipients and the consequences of misinterpreting radiologic findings. In this instance, the assumption that a small hepatic lesion represented metastasis delayed appropriate surgical intervention and subjected the patient to systemic chemotherapy unnecessarily.

False-positive interpretations in post-transplant patients are not uncommon due to chronic inflammation, regenerative nodules, and altered vascular dynamics. These confounders demand a high level of diagnostic scrutiny, particularly when treatment decisions carry high stakes.

Liver transplant recipients often present to the emergency department with vague or nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, or fatigue, complaints that can easily be attributed to medication side effects, chronic liver disease, or infection. However, in this high-risk group, clinicians must maintain a broad differential diagnosis that includes malignancy. Red flags in the ED setting may include new hepatic lesions on imaging, unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding, or systemic signs of malignancy such as cachexia or rapidly declining functional status. Early multidisciplinary input and caution against anchoring on benign explanations can be crucial to avoiding diagnostic delay in this population.

This case also illustrates anchoring bias, a cognitive pitfall where early diagnostic assumptions persist despite new evidence. The presumption of metastasis anchored management decisions and delayed consideration of alternate explanations. Employing diagnostic timeouts, revisiting differentials at key decision points, and using structured frameworks such as the “dual process model” may help safeguard against premature closure.

A multidisciplinary approach proved essential in this case. It was only through collaborative tumor board reassessment and high-resolution follow-up imaging that the hepatic lesion was correctly identified as benign. This reclassification fundamentally changed the therapeutic trajectory and enabled definitive surgical management.

Additionally, the case underscores the delicate balance between immunosuppression and oncologic control. The patient’s immunosuppressive regimen limited therapeutic options and introduced surgical risk.

This required precise coordination between oncologists, transplant surgeons, and gastroenterologists. Such interplay further emphasizes the need for personalized, multidisciplinary care in managing malignancies in transplant recipients.5–9

Conclusion

Liver transplant recipients are uniquely vulnerable to diagnostic errors due to the dual complexity of malignancy and immunosuppression. This case illustrates how misdiagnosis can lead to overtreatment and delay curative options. It also affirms the value of ongoing re-evaluation, imaging precision, and multidisciplinary teamwork. As transplant survival improves, clinicians must remain vigilant and avoid anchoring bias in the assessment of new lesions. Tailored, patient-specific care and repeated diagnostic scrutiny are vital to improving outcomes in this population.