Introduction

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), known as the COVID-19 pandemic, began in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, and spread to Europe, the USA, and eventually the globe. During the pandemic surge, surgical practice was confined to top emergency cases, but urgent cases and cancer patients were gradually accommodated.1 During the pandemic, the surgical department resources were reallocated to bridge the gap in the healthcare system. Surgeons and their staff were shifted to Intensive Care Units (ICUs) or the Emergency Room (ER), while beds, ventilators, surgical high-dependency units (HDU), and ICUs were used for COVID-19 patients. The main issues with this change were to provide efficient surgical emergency and oncological services and to protect the patients and surgical staff against COVID-19. Priority criteria were set depending on the patient’s clinical condition and the urgency of surgical intervention needed to avoid delay or unnecessary early intervention.2–5 During the pandemic surge, most institutes stopped or reduced their elective work to the minimum, and only life-saving operations or oncological surgeries were done. This provided more staff and resources for COVID-19 patients’ care and the protection of health professionals. Staff safety and mental, physical, and financial well-being were crucial in planning and managing the pandemic.5–7 Taking many precautions to post a patient for emergency surgery was essential. The patients and their families should not have COVID-19 symptoms for at least one week. A test or CT scan may be needed in some patients to exclude suspected infection. The patient and family should be counseled about the possibility of getting an infection from the hospital, the possible need for ICU admission, and the complications of COVID-19 in surgical patients. In addition, the process may encounter sudden changes regarding the timing of the operation, the surgeon doing the procedure, or the availability of any required special care.8,9

Our study is an example of providing surgical services for emergency cases and cancer patients during the surge of the pandemic in a situation of scarce resources.

Methods

This is a retrospective observational study of the Department of Surgery in Kassala Police Hospital’s response to the pandemic between March 2020 and July 2020.

Inclusion Criteria:

-

Surgical patients admitted for emergency surgical conditions or cancer.

-

Patients admitted in the period between March 2020 and July 2020.

-

Patients with complete medical records.

-

Patients or their guardians must have consent to participate in the study.

Exclusion Criteria:

-

Patients with missing or insufficient data

-

Patients admitted for non-surgical conditions

-

Patients who were treated as outpatients.

-

Patients who refused to participate in the study.

The study included 313 patients who were admitted to the department of surgery for emergency surgical conditions or treatment of cancer. Data were collected from patients’ records and phone calls to some patients. The authors developed a questionnaire and validated it by using content and expert validation. A pre-test was done with 15 patients to test its understandability and clarity. The questionnaire was composed of socio-demographic and clinical data. The data included patient age, age group, gender, diagnosis, type of operation done, mode of presentation, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, ICU admission, postoperative morbidity and mortality, and if the patient developed COVID-19 infection after admission. All patients admitted within the study period were included to avoid selection bias. The outcome measures were hospital stay, need for ICU admission, postoperative morbidity, and mortality. The ethics and research committee in Kassala Police Hospital approved the study, and relevant guidelines and regulations were carried out in all procedures and methods. All patients or their guardians gave consent to participate in the study. All patient’s data were analyzed anonymously to ensure confidentiality.

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, we used SPSS version 26.0. a descriptive analysis was used for all included variables using mean SD for all continuous variables and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. We used Chi-Square and T-tests for bivariate analysis. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Protocol and procedures

At the beginning of the pandemic, after diagnosing the first case in Sudan and the index case in our state, we stopped all surgical services and immediately started the precautions against COVID-19. The first case of COVID-19 in our state was diagnosed on March 13, 2020; we started our emergency services on March 21, 2020, and semi-emergency for cancer patients on April 6, 2020. We followed WHO recommendations and other available guidelines by strictly using masks, social distancing, avoiding in-person communication, using disinfectants, and locking down all the clinics and operating theatres. We had a committee that included representatives from hospital management, clinicians from all departments, nursing and operative theater staff, public health and infection control, and finance department representatives. The committee was in continuous virtual meetings using WhatsApp groups, getting constant updates from clinicians about new guidance or recommendations about the control of COVID-19. The committee worked in continuous effective communication and coordination with the Infection Control Department in the State Ministry of Health, the Respiratory Center in Kassala Teaching Hospital, and the State Isolation Center. In the hospital, all the high-risk groups, like people with diabetes, pregnant ladies, anyone with immunity issues, and old age in the staff, were given open leave. There was a regular screening of the staff, and those who tested positive went for home isolation. Any staff member with intense symptoms will be isolated even without testing. Personal Protection Equipment PPE will be used only when nursing or operating on suspected or proven positive patients. Waterproof gowns, local-made face shields, and N95 masks were used for asymptomatic or proven negative patients. The staff were arranged in small groups and kept to the minimum according to need to avoid exhaustion. Motivation and psychological support of the staff were part of the committee’s regular work. A simple triage point was created using a temporary shelter in front of the hospital with one resident doctor and one expert nurse. They categorize the patients and make immediate decisions as follows:

-

Symptomatic patients who are clinically stable will be sent to the Respiratory Center in Kassala Teaching Hospital.

-

Symptomatic patients who need immediate supplementary oxygen therapy will be transferred to our transient isolation station, which has three beds, monitors, and an oxygen supply but no invasive ventilation. After stabilization, the patient will be transferred to the Respiratory Center.

-

Asymptomatic patients with emergency surgical conditions will be admitted to the hospital to get a surgical review and COVID-19 test. If he is clinically well, he can wait for the test result; otherwise, we will proceed with the operation immediately.

-

Symptomatic emergency surgery cases will have the test and chest CT scan. If clinically stable, the results are reviewed first. Otherwise, we proceed with the surgery and consider the patient positive until the results are out.

-

All COVID-19-positive patients will have their surgery deferred till they improve. The operation will be done if they deteriorate due to their surgical illness.

-

Asymptomatic cancer patients with negative tests will be prepared for the surgery as outpatients to minimize the length of hospital stay.

-

Symptomatic and positive patients will have a new date after two or four weeks, and they should test negative to have their operation done.

We adopted the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocol in all possible situations to minimize hospital stays. Post-operatively, the patient will be discharged as soon as possible, and follow-up will be through phone calls, pictures of the wound, or video calls. There is an isolated “clean” ICU if a surgical patient needs ICU care, while there is a COVID-19 ICU for infected patients.

Results

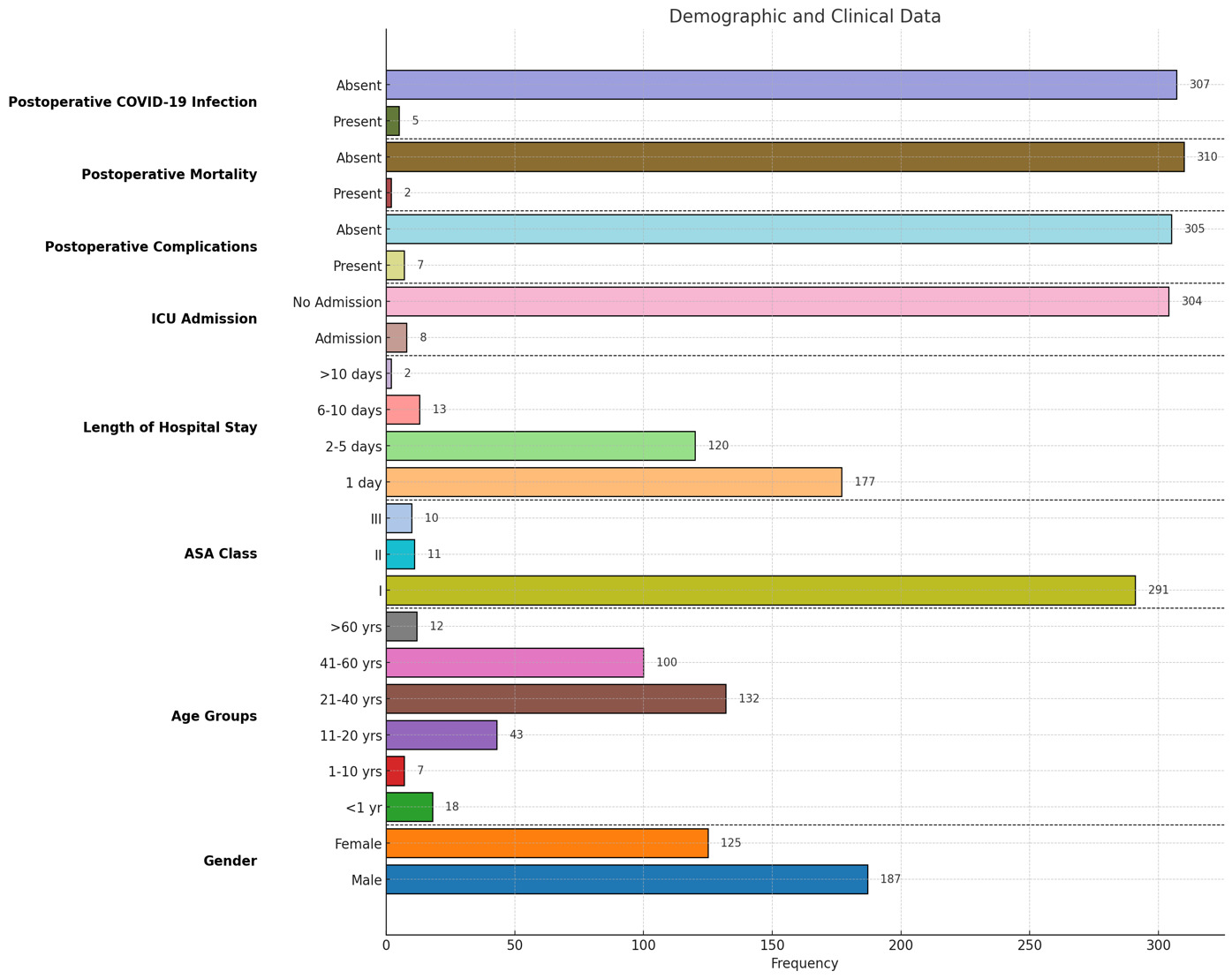

The study included 313 patients admitted to the Department of Surgery, with 312 undergoing operations and one treated conservatively. Emergency cases constituted the majority (77.6%), while cancer cases accounted for the remaining 22%. The youngest patient was one day old, and the eldest was 74 years, with a mean age of 31.4 years. Male patients predominated (59%), and the most common emergency procedures included appendicectomy, abscess drainage, and laparotomy for trauma, while breast and colorectal cancer surgeries were the most frequent cancer-related operations.

Most patients (93.3%) were ASA class I, with fewer in ASA classes II (3.5%) and III (3.2%). A significant association was observed between higher ASA class and more extended hospital stays, ICU admissions, postoperative morbidity, and mortality (p < 0.001). Postoperative complications occurred in 2.2% of cases, with a mortality rate of 0.6%. Both deaths were associated with postoperative complications rather than COVID-19. ICU admission was significantly linked to postoperative complications (p < 0.001).

The mean hospital stay was 2.14 days, with longer stays significantly correlated with an increased risk of postoperative COVID-19 infection (p < 0.001). Postoperative COVID-19 infection occurred in 1.6% of patients, with a higher prevalence in cancer cases than in emergency cases. ASA class is also significantly associated with postoperative COVID-19 infection (p = 0.01).

During the study period, six patients tested positive for COVID-19 preoperatively, five of whom were cancer patients whose surgeries were rescheduled. Five out of 20 hospital staff members tested positive and were isolated for two weeks(one doctor, two anesthetic technicians, and two scrub nurses). Figures 1, 2, and 3 display more detailed results.

A multivariate analysis examined all patients’ variables against the clinical outcomes (Table 1). It shows that ASA class II–III was an independent and statistically significant predictor of all three outcomes: postoperative complications, ICU admission, and postoperative COVID-19 infection. Cancer-related procedures were associated with significantly higher odds of ICU admission and postoperative COVID-19 infection compared to emergency procedures. More extended hospital stays (>3 days) independently increased the risk of ICU admission and COVID-19 infection. Age >60 was significantly associated with a higher risk of COVID-19 infection but not independently with complications or ICU admission. Sex was not a significant independent predictor in any outcome.

Discussion

Our hospital was nominated as the state’s main center of emergency surgical services during the pandemic. Therefore, more surgical patients were directed to us, and COVID-19-suspected patients were diverted to the respiratory or isolation center, which may explain our study’s low incidence of COVID-19 infections. This has prevented the reduction of emergency case numbers during the pandemic, as our emergency case incidence was similar to the non-COVID periods. Our maintained frequency of cases and the complicated presentation of cases like appendicitis and diverticulitis were comparable to other studies.10

Other studies showed a decrease in the number of emergency cases, as stated by Giovanni et al. in the results of the audit conducted by the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) and the Association of Italian Hospital Surgeons (ACOI—Associazione dei Chirurghi Ospedalieri Italiani).11 Strict lockdown rules resulted in delayed management of emergency cases, leading to poor outcomes in some countries, as the patients presented with more complicated clinical conditions, as stated by Rashdan et al.12 and Surek et al.13 showed that there was an overall reduction in some acute surgical cases although some of them maintained the same frequency as pre-pandemic rates (e.g., acute appendicitis); however, more complicated presentations were seen. The reduction in emergency cases was partially explained by the fear of patients being hospital-admitted or having a high incidence of COVID-19, leading to more strict precautions.14 Reichert et al. concluded the WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey by stating that there was a reduction in patient numbers and more complicated presentations were seen secondary to delay in admission, diagnosis, and intervention, which may explain the poor outcomes.4 Pirozzolo et al. stated that the number of emergency cases was not reduced, but there was a delay in treatment, leading to poor outcomes.15

For safe practice, further precautions were recommended; these included the provision of all protection equipment for the surgical staff, restricting the staff to the need, restricting visitors, providing special rooms for counseling and patient assessment, minimizing face-to-face services, and adopting enhanced recovery after surgery. In addition, a protocol for testing and counseling patients is mandatory.2 With scarce resources, we started providing services for emergency and cancer patients. Even with minimal resources, good outcomes are possible with planning, reallocating resources, and setting algorithms or workflow charts. The health authorities’ healthcare workers should make all efforts to avoid a significant drop in the standard of surgical care during disasters.5,16–18

Regarding adverse outcomes of the surgery during the surge of the pandemic, our mortality rate (0.6%) and postoperative complications rate (2.2%) were comparable to non-COVID times. Although we had five patients who got COVID-19 infection, there was no COVID-19-related mortality, and none of the patients needed invasive ventilation. That was an indicator of the capacity of healthcare professionals to accommodate changes and shoulder the challenges brought by the pandemic. These findings agree with a retrospective study used data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database, which included 7436 patients who had operative procedures in the period from February 2020 to December 2022; there was no increase in the overall 30-day mortality or morbidity when a comparison was made between patients who had their operation during the pandemic or after it.19,20

Other studies showed more adverse outcomes than our study, as the number of patients who developed COVID-19 in the postoperative period was higher, as shown in the collaborative research by Osorio et al.21 A study from Canada (Balvardi et al.) showed a reduction in cases compared to pre-pandemic periods. Still, interestingly, they agreed with our research on shortening patients’ length of hospital stay.22 Chrysos et al. from Germany stated that there was a reduction in the number of patients in a tertiary center while there was an increase in numbers in other smaller hospitals.23

COVID-19 had a significant impact on the treatment of cancer patients. In our study, the five cancer patients who tested positive for COVID-19 had their surgery at a later date when they were asymptomatic and negative for the virus. In our study, we had no mortality among five preoperatively and three post-operatively diagnosed COVID-19 patients. Deo et al. stated similar results with their working protocol, testing policy, and MDT approach to cancer patients’ they managed to have non-inferior, if not better, results regarding postoperative morbidity and mortality.24 Kishan et al. stated increased mortality but not morbidity among cancer patients with COVID-19 infection,25 while Christian et al. highlighted the increased poor outcomes and increased number of locally advanced tumors due to delayed presentation.26

To improve the outcomes, the Global Forum of Cancer Surgeons (GFCS) worked on creating roadmaps and guidelines to serve situations similar to the pandemic by addressing protocols, staff protection, patient care, and resource management.27 The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted the timely diagnosis and management of colorectal cancer (CRC), resulting in delayed surgical interventions and worsening outcomes, including increased mortality. During the pandemic, prioritizing healthcare resources for COVID-19 patients led to postponements in elective surgeries, including those for CRC. A retrospective study in Japan reported a rise in obstructive colorectal cancers during the pandemic, likely reflecting delays in treatment due to resource constraints and fear of infection among patients seeking care.28 Similarly, a Romanian analysis highlighted disruptions in colon cancer care, including reduced surgical capacity and deferred interventions, contributing to disease progression and higher complication rates.29 Moreover, data from Spain indicated that the pandemic’s strain on healthcare systems resulted in delayed CRC diagnoses and treatments, exacerbating cancer-related mortality.30 Collectively, these findings underscore the critical need for strategies to mitigate the indirect consequences of global health crises on cancer care. Long delays in surgeries for cancer patients can lead to a substantial increase in mortality with a reduction in survival, and it leads to a significant backlog of cases.31 In our study, the surgeries were deferred for 2-4 weeks for only five patients with positive COVID-19 tests, which was acceptable and anon-avoidable.

For the emergency cases, we followed our protocol by minimizing staff to the minimum needed, avoiding unnecessary personal contact, and limiting visitors to one relative. These precautions positively impacted the outcomes, matching the results of Simone et al.32 Maria et al. stated that more than 30% of their patients were managed conservatively to reduce the postoperative mortality observed in COVID-19 surgical patients.33 In our study, only one patient (0.6%) with acute appendicitis was managed conservatively. We maintained effective communication and cooperation with related authorities and other departments. The team spirit was valued through equal exposure, working hours, and psychological support. Those were determinant factors in the success of the whole process.6,7 Five (25%) of our staff had COVID-19 infection and, fortunately, recovered well after home isolation; other studies showed incidence reaching 79% among their staff.25

One of the hidden faces of the COVID-19 pandemic’s effect on surgical practice was the moral and psychological aspects. The surgical staff had to change their work environment and their concept from patient-centered care to community-focused care.34,35

On a retrospective evaluation of our timetable of actions, we were reasonable. We stayed caught up, and despite our limited resources and infrastructure, we managed to find our way out of the disaster. Our first case of COVID-19 in our state was diagnosed on March 13, 2020. We started our emergency services on March 21, 2020, and semi-emergency for cancer patients on April 6, 2020. The regular elective surgical services were re-introduced on July 5, 2020, with all the appropriate precautions. Compared to other countries’ responses, we found that the first cases of COVID-19 were identified in China in December 2019, and the first case in the USA was on January 20, 2020. Between the 9th and March 19, 2020, guidelines and protocols were released from the regulating health authorities.36 The short length of hospital stays also helped to reduce the incidence, as 177(56.7%) patients stayed for one day or less, and the mean was 2.14 days.

In our cohort, cancer-related complex procedures included radical cholecystectomy (2 cases), distal gastrectomy (3 cases), anterior resection (4 cases), sigmoid colectomy (3 cases), and gastrojejunostomy (3 cases). Emergency procedures comprised colonic resection with colostomy (4 cases), laparotomy for intestinal obstruction (5 cases), perforated duodenal ulcer repair using Graham’s patch (4 cases), combined below- and above-knee amputations (8 cases), and a ruptured spina bifida repair (1 case). These surgeries, representing 11.9% of total operations, prioritized oncological and emergency care, reflecting the hospital’s advanced surgical capabilities and perioperative protocols despite COVID-19 challenges.

Postoperative outcomes were poorer in this group. Six of eight patients (2.6%) requiring ICU admission were from this cohort. Five of seven patients (2.2%) with postoperative complications belonged to this group. Both mortalities (0.6%) occurred in the complex surgery cohort. Additionally, five patients (1.6%) developed postoperative COVID-19 infections, including three from this subgroup. These findings align with global studies,31,37 underscoring our hospital’s dedication to high-quality care for complex cases while achieving reasonable outcomes under challenging conditions.

Limitations and challenges

This retrospective observational study is conducted in a single center, making its generalizability difficult or questionable for high-volume centers, different populations, or different healthcare setups. Moreover, this limits the ability to establish causal relationships between the identified risk factors and clinical outcomes. The absence of a control group further restricts comparative analysis, making it difficult to determine the relative impact of specific variables such as ASA class or procedure type.

Although we tried to avoid selection bias by including all patients, it remains a possibility. Unmeasured confounding variables, such as socioeconomic status, nutritional status, or access to follow-up care, may have influenced the observed outcomes.

Additionally, religious, cultural, and social beliefs must be sensitively navigated to ensure compliance with testing and treatment protocols. These factors may have influenced the completeness and uniformity of data collection. Administrative and logistical difficulties were additional challenges in maintaining standardized care delivery and documentation.

Conclusion

Effective emergency and oncological surgical service provision is achievable during a pandemic in resource-limited settings by implementing structured protocols, ensuring strong leadership, and enhancing teamwork. Our study highlighted that adherence to safety measures, careful patient triage, and efficient resource allocation will maintain essential surgical services with minimal postoperative complications, low mortality, and limited COVID-19 transmission among patients and staff.

Conflict of interest

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

Funding

None.

Ethical clearance

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research and Ethics Committee at Kassala Police Hospital

Acknowledgment

We thank Brigadier General Abdel Rahman Almadani Abdallah, the hospital’s Administrative Director, and Major Abdallah Mohammed Abdallah, the Head of the Director’s Executive office, for their support. We also thank Dr. Mohammed Elfatih Yousif from the Department of Internal Medicine in Central Police Hospital for his advice and ideas.