Introduction

Non-physician practitioners (NPPs), physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs), are essential in the workforce planning and patient care aspects of health care. Between 2003 and 2014, the number of graduating nurses has grown from 6,611 to 18,500. In equal proportion, this trend has been observed for graduating PAs as well.1 While it was believed that NPPs would provide better value-based care, a recent study debunked this myth.2 Furthermore, some argue that the increased ability for NPs and PAs to practice independently of physicians and ambiguous terms, such as "advanced practice providers’’ have led to confusion for patients in deciding from whom they should seek care. It is speculated these factors may exacerbate issues of health literacy as patients may be unfamiliar with differences in training and the services provided by NPs, PAs, and physicians.3

While physicians complete four years of medical school followed by three to seven years of residency and fellowship, most physician assistants complete their studies in two to two-and-a-half years and NPs study for two years. The training through which PAs and NPs learn to treat patients allows them to address common presentations of disease and apply pattern recognition to common patient cases. However, compared to physicians, these providers would be far less equipped to handle rare and complicated conditions. A study involving 1,169 diabetic patients with elevated blood pressure found that for complex cases, critical decisions that needed to be made varied between NPPs and physicians.4 Another study concluded that a major difference in treatment between NPs/PAs and physicians is that NPPs are more likely to focus on education and counseling while the latter group could offer secondary prevention of disease.5 For some patients in need of timely care, their conditions and treatment options may be outside the scope of their knowledge. This is compounded by growing concern that many patients cannot differentiate NAs/PAs from physicians and how to seek reliable information to clarify their differences before deciding which one to visit.6

As of March 2023, 28 states have permitted full autonomy for NPs.7 Our study aims to measure patients’ understanding of NPs, PAs, and physicians in health care and who they prefer to visit.

Method

Recruitment, data collection, and statistical analysis

Two hundred (N = 200) adults ages 16 and up were surveyed via an anonymous online survey platform that uses random device engagement and organic sampling. Random Device Engagement applies artificial intelligence (AI) to reach users on their devices as they go through their daily lives. The survey platform partners with many organizations to recruit random participants who are eligible to participate in the survey. The AI technology ensures that each participant can only answer the survey one time and prevents participants from entering suspicious answers to questions. All results that were generated by the survey tool for univariate analysis included weighting for age, gender and geographic region. The data were analyzed using JMP Pro 14.1 for Windows. This study was given an exempt determination (study #2022-900) by our institutional review board.

The survey

The survey consisted of 13 multiple-choice questions where respondents could only choose one answer for each question. The first question asked participants what type of healthcare provider they see when they go to their “doctor’s” office. The next 5 questions asked respondents about their preference when it comes to handling their care (physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant), the work training needed to be a physician, and the experience each position requires. The next 3 questions asked participants about whether nurse practitioners should be able to give care to patients without physician supervision and if they would prefer them over board-certified doctors for surgery. The next 2 questions asked about their preference in an emergency room setting and who they encounter most often. The final 2 questions asked respondents whether they would like to refer to providers by their credentials and if nurses should be able to prescribe medications, another task that physicians usually do.

Results

A total of 200 adults responded to this survey, 55% female and 45% male. These participants ranged in age from 17 to 72 and had a median age of 38 years with an interquartile range of 31 to 45. The individuals who completed the survey were predominantly White, accounting for 66% of the cohort, followed by Black at 17%, Hispanic at 5.5%, Latino at 3%, Asian at 2% and Multiracial at 1%. 3% of respondents selected “other” and 2.5% of participants preferred not to disclose their race. The majority of individuals said that they had finished high school (35.5%) or university (30.5%). After those 2 categories, the remaining participants said that they completed a postgraduate degree (20%), vocational technical college (12%) and middle school (2%). The largest proportion by income status identified as low-income individuals (46.5%) meaning they earn under $50,000 a year. Of that 46.5%, 24% identified as earning between $25,000-$49,999 a year and 22.5% identified as making less than $25,000 a year. The second highest batch of respondents, at 28%, identified as middle-income individuals, meaning they make between $50,000-$99,999 a year. Of that 28%, 15% identified as earning between $75,000-$99,999 a year and 13% between $50,000-$74,999 a year. The remaining respondents, at 19.5%, designated themselves as high-income individuals, meaning they make between $100,000 or more a year. Of that 19.5%, 7% reported that they earn $150,000 or more a year, while 6.5% selected between $125,000-$149,999 a year and 6% reported earnings between $100,000-$124,999 a year. Each survey question and its responses are explored in more detail in this section.

When you go to the doctor’s office, who do you see?

The largest number of survey respondents, at 63% (126 out of 200), indicated that when they go to the doctor’s office, they see a physician with the credentials MD or DO. Following those who selected physician, 17% (34 out of 200) indicated that they see a nurse practitioner (NP), 11.5% (23 out of 200) believed that they just see a “healthcare provider”, 4.5% (9 out of 200) said that they see a physician assistant (PA) and 4% (8 out of 200) were unsure about the professional they see at the doctor’s office.

How many hours of clinical training do you think your primary care physician gets?

Participants who responded to this question selected answer choices in similar frequencies. 25.5% (51 out of 200) believe that primary care physicians complete between 5,000-10,000 hours of clinical training, 25% (50 out of 200) think that primary care physicians complete over 20,000 hours of clinical training, 23.5% (47 out of 200) believe that primary care physicians complete between 10,000-15,000 hours of clinical training and 18.5% (37 out of 200) presume that primary care physicians complete between 15,000-20,000 hours of clinical training. The remaining 7.5% (15 out of 200) thought that the number of hours that a primary care physician trained for was not reflected in the answer choices provided.

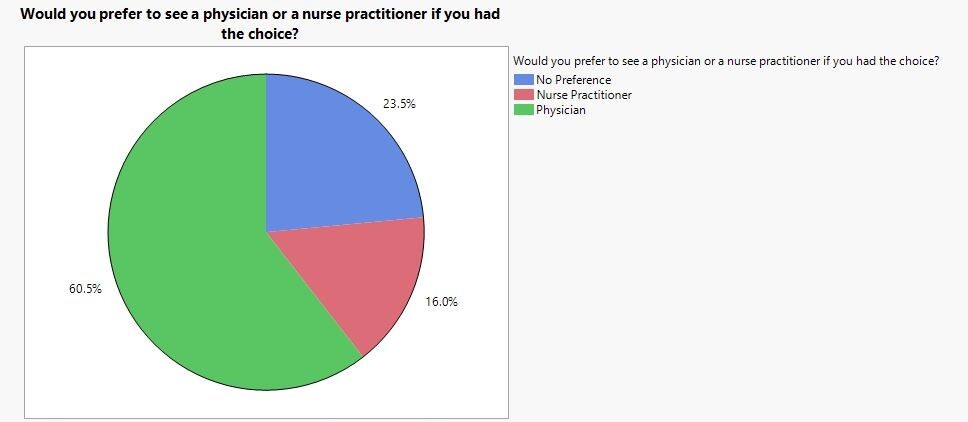

Would you prefer to see a physician or a nurse practitioner if you had the choice?

The number of survey participants who preferred to see physicians vastly exceeded those who preferred to see nurse practitioners when given the choice with 60.5% (121 out of 200) selecting the option of preferring a physician compared to only 16% (32 out of 200) preferring to see a nurse practitioner. The remaining 23.5% (47 out of 200) did not have a preference (Figure 1).

How many years does a physician train for after high school?

64% of participants (128 out of 200) answered that physicians train for 6-11 years after high school, with 33% (66 out of 200) believing that physicians train for 6-8 years and 31% (62 out of 200) thinking that physicians train for 8-11 years. 10% (20 out of 200) of survey-takers reported that physicians train for 4-6 years and another 10% (20 out of 200) reported that physicians train for 11-18 years. The remaining 16% (32 out of 200) were unsure about the length of training physicians go through after high school.

How many years does a physician assistant train for after high school?

The majority of participants, 63.5% (127 out of 200), said that physician assistants train for 4-7 years after high school, with 32% (64 out of 200) believing that physician assistants train for 5-7 years and 31.5% (63 out of 200) thinking that physician assistants train for 4-5 years. 16% (32 out of 200) said that physician assistants train for 7-10 years. The remaining 20.5% (41 out of 200) were unsure about how long physician assistants train for after high school.

How many years does a nurse practitioner train for after high school?

More than half of respondents, 53.5% (107 out of 200), indicated that nurse practitioners train for 3-6 years, with 28% (56 out of 200) believing that nurse practitioners train for 5-6 years and 25.5% (51 out of 200) suggesting that nurse practitioners train for 3-5 years. 14.5% (29 out of 200) of participants thought that nurse practitioners train for 7-10 years and 12.5% (25 out of 200) of the cohort believed that nurse practitioners train for 2-3 years. The remaining 19.5% (39 out of 200) were unsure about how long nurse practitioners train for after high school.

If you were to have surgery, would you prefer a board-certified physician anesthesiologist or a certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA)?

The majority of survey-takers, 65.5% (131 out of 200), preferred a board-certified physician anesthesiologist to assist their hypothetical surgery compared to 18% (36 out of 200) who preferred a certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA). The remaining 16.5% (33 out of 200) did not have a preference.

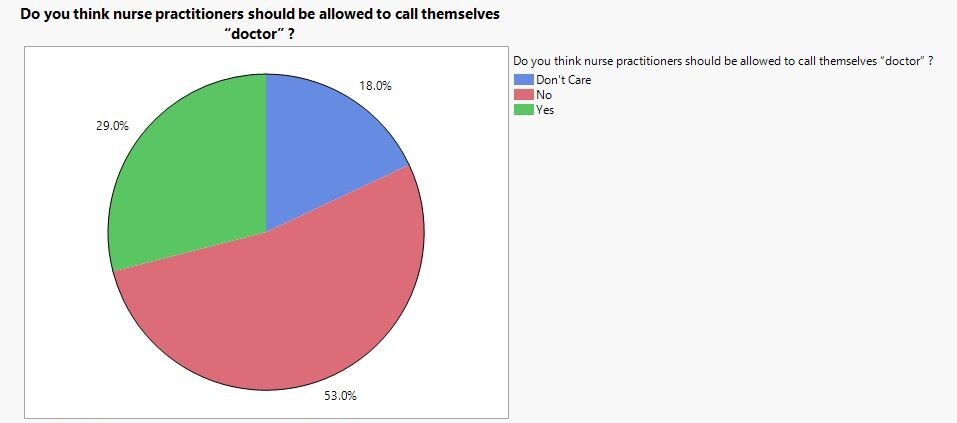

Do you think nurse practitioners should be allowed to call themselves “doctor”?

The majority of participants said that they do not believe nurse practitioners should be allowed to call themselves “doctors” at 53% (106 out of 200) compared to those who believed that nurse practitioners should be allowed to call themselves “doctors” at 29% (58 out of 200). The remaining 18% (36 out of 200) indicated that they did not have a preference (figure 2).

Do you expect nurse practitioners to be supervised by physicians (vs practicing independently)?

The largest number of respondents, at 64% (128 out of 200), stated that they expect nurse practitioners to be supervised by physicians while 24.5% (49 out of 200) indicated that they would prefer nurse practitioners practicing independently without physician supervision. The remaining 11.5% (23 out of 200) said that they did not have a preference/

When you go to the emergency room (ER), do you expect a physician to direct your care?

The vast majority of participants, at 74% (148 out of 200), believed that a physician should direct their care when in the ER compared to only 13.5% (27 out of 200) who believed that a physician was not required. The remaining 12.5% (25 out of 200) did not have a preference.

When you go to the ER, do you ask who your “provider” is?

A larger number of respondents, at 61.5% (123 out of 200), indicated that when in the ER, they did not ask who their “provider” is compared to 38.5% (77 out of 200) who did ask who their provider is.

Do you favor abandoning the term “provider” in favor of the person’s actual credentials (physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant)?

The majority of respondents, at 57.5% (115 out of 200), preferred to call their provider by their actual credentials instead of just “provider” compared to only 20% (40 out of 200) who would prefer to just call their provider “provider”. The remaining 22.5% (45 out of 200) did not have a preference (Figure 3).

Do you believe nurse practitioners should be allowed to prescribe medications (including controlled substances) without physician oversight?

In contrast to previous questions, where the majority of respondents tended to prefer physicians over nurse practitioners for aspects of their care, more participants answered in this question that nurse practitioners should be allowed to prescribe medications without physician oversight. More specifically, 47.5% (95 out of 200) were content with nurse practitioners prescribing medications without physician oversight compared to 36.5% (73 out of 200) who wanted physicians to have some say in the medications patients get. The remaining 16% (32 out of 200) did not have a preference (figure 3).

Discussion

One goal for this study is to measure patients’ knowledge of various healthcare providers. The survey’s first question asked participants who they encounter when they visit a doctor’s office. Of 200 respondents, 31 (15.5%) indicated that they are unsure of the provider’s qualifications or believe that this individual is simply a “healthcare provider”. It is reasonable to believe this cohort of participants do not make specific visits for health concerns from an objective basis. This is concerning, as issues of health literacy have been linked to increased hospitalization and worse outcomes.8 It is thus possible and likely these patients are not receiving the care that they need and may be tangibly suffering as a result. Similar levels of health literacy have been observed before in patients treated at an Orthopedics Sports Medicine clinic, wherein patients expressed uncertainty about which services should be performed by physicians or NPs and PAs.1 One contributor to how worse outcomes arise is that physicians are sometimes unable to recognize when a patient has low health literacy. If this disparity goes unacknowledged, patients may not be empowered with the knowledge to take medications as prescribed or make the lifestyle changes recommended by the physician.9 A physician’s ability to identify and improve a patient’s level of health literacy could be compounded by, as evidenced by our survey question, the fact that many of these patients are not visiting the correct provider in the first place.

Our survey included a question to assess the cohort’s perspective on which providers should call themselves “doctors”. 58 out of 200 participants (29%) reported that NPs and PAs should call themselves doctors, while 18% did not care. While extending this terminology to NPs and PAs may show reverence towards their services, it could also be misleading. The term “doctor” originates from the Latin word, “docere”, meaning a scholar. As NPs and PAs practice after undergoing training that is similar in duration to a masters degree, one author has argued that “doctor” should be reserved for those holding an MD or PhD.10 On the other hand, in certain instances, NPs and PAs have been found to provide treatment with similar clinical safety and health outcomes as physicians; for this reason, it has been argued these groups are deserving of the name doctor.11 For some, this is a contentious topic and remains unmeasured how similar titles for different providers may affect patient literacy. Table 1 provides a comparison of Physician, Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant training requirements.

An interesting finding in this study was that 47.5% of the cohort (95 out of 200) would like nurse practitioners to be able to prescribe medications without physician oversight compared to 36.5% (73 out of 200) who wanted physicians to have influence on the medications patients get. This was the only question in the survey where participants predominantly answered in favor of PAs and NPs. One explanation could be that patients report in their best interest—answering that NPPs should be able to prescribe medications independently means greater access for patients and fewer restrictions. A veteran population was sampled to measure preferences for having single versus multiple prescribers of pain medication. In this study, most participants reported wanting multiple to maximize timeliness and access.15 Conversely, some patient populations have demonstrated a concern about medication safety and have even requested written information attached with prescription to better understand the reasoning behind its use.16 Polling this question in a larger sample size could be an improvement on this study to understand patient perspectives in a cohort that is more generalizable and that offers greater external validity.

Limitations

A sample size of 200 participants does not fully encompass the diversity of people in our country who seek healthcare, or their health literacy level. Survey research is also susceptible to response bias wherein participants may not submit answers entirely accurately or truthfully, or may answer what they think they are “supposed to”. By using a third-party survey tool, there is also a sampling bias as respondents participated for an incentive by the provider. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable information about the patient experience- the perception of care and who is providing it by the patients.

Conclusion

This study helps provide insight to existing patterns of health illiteracy and confusion regarding various roles in health care.