Introduction

Intestinal stomas, including ileostomies and colostomies, are surgically created abdominal openings to divert bowel contents, commonly indicated in colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), trauma, and bowel obstruction or perforation. Stomas may be temporary or permanent, depending on pathology and surgical indication. Over 1 million people globally live with stomas, with around 100,000 new cases annually in the U.S.1 First performed in the late 18th century, stoma surgery has evolved significantly in techniques, postoperative care, and appliance technology.2Stoma creation may be an emergency procedure for cases like bowel perforation, or elective, as in surgeries for cancer or Crohn’s disease.3 While some stomas are reversable, permanent stomas are required in cases of severe bowel dysfunction or extensive resections.4 Complications, which affect 10%-70% of stoma patients, are either early (e.g., skin irritation, necrosis, infections) or late (e.g., parastomal hernias, prolapse).5–7 Multidisciplinary team involving surgeons, stoma nurses, nutritionists, and physical therapists is essential.7 Nutritional issues, particularly with high-output ileostomies, carry risks of dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and malnutrition.8 Psychological effects, such as anxiety and depression, affect 50% of patients, requiring support and counseling by expert professionals.9Controversies in stoma management are related to timing of closure, indications of diverting stomas, and the use of alternative measures such as primary anastomosis.10 Although diverting stomas may reduce anastomotic leaks, but they are associated with a set of complications. Financially, stoma-care increases healthcare costs by 30%-50%.11

This review classifies stomas; discusses complications; explores nutritional, psychological, and social impacts; and addresses controversies. By synthesizing evidence, it aims to equip healthcare providers with strategies to optimize stoma care and improve patient clinical outcomes.

Methodology

1. Study Design

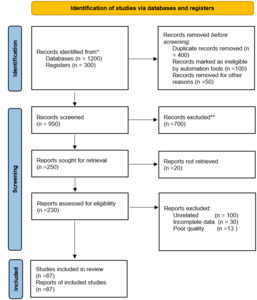

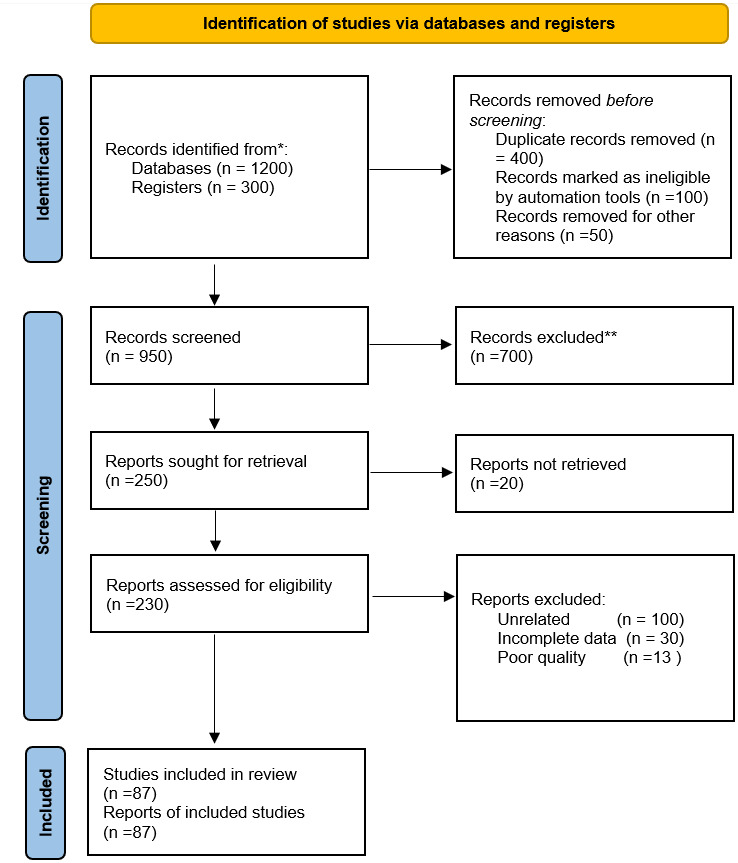

This systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines to review evidence on stoma classification, complications, management, and controversies.

2. Search Strategy

A comprehensive search across PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar covered studies from 2000 to 2023. Keywords included “intestinal stoma,” “ileostomy,” “colostomy,” “stoma complications,” and related terms. Reference lists of relevant articles were manually screened.

3. Inclusion Criteria

-

Studies on classification, complications, management, or controversies of ileostomies/colostomies.

-

Articles addressing both temporary and permanent stomas, including psychological, nutritional, and financial impacts.

-

RCTs, cohort studies, case series, and clinical guidelines.

-

English, peer-reviewed publications.

4. Exclusion Criteria

-

Studies focused on pediatric populations, non-intestinal stomas, or unrelated surgeries.

-

Non-peer-reviewed articles, conference abstracts, and expert opinions without data.

-

Studies with incomplete data on complications or outcomes.

5. Data Extraction

Three independent reviewers screened and selected studies, then extracted data on study design, stoma type, complications, psychosocial and nutritional impacts, management controversies, and financial burdens. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

6. Quality Assessment

RCTs were assessed with the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool; cohort and observational studies with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Evidence was graded using GRADE.

7. Data Synthesis

Data were qualitatively synthesized and categorized by stoma classification, complication types, nutritional support, psychosocial impacts, and management controversies.

8. Limitations

Limitations include variability in study quality, publication bias, lack of meta-analytic synthesis, and restriction to English-language publications, potentially affecting generalizability.

9. Ethical Considerations

No ethical approval was needed as this review analyzed published studies, all checked for original ethical compliance.

DISCUSSION

A. Classification of Stomas

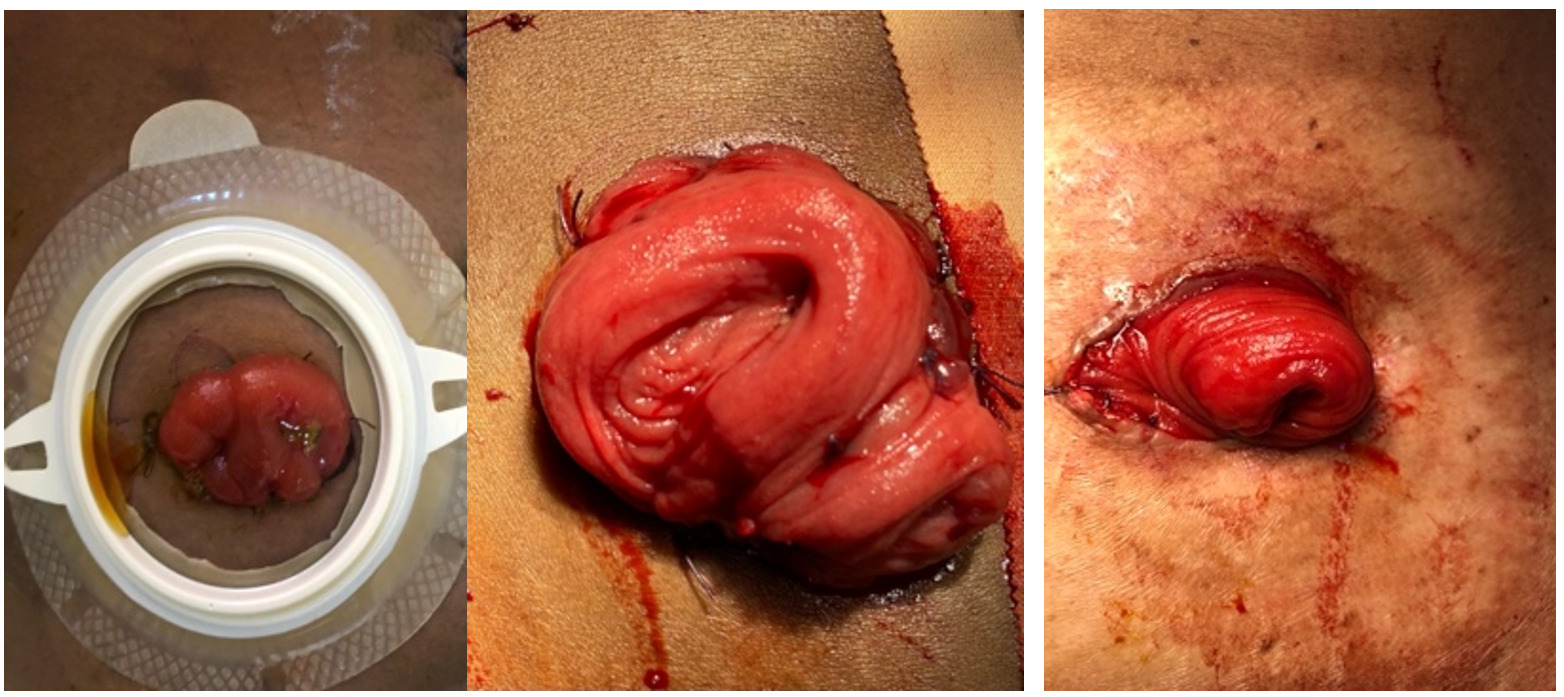

Intestinal stomas are classified by anatomical site, presentation, fate, and construction, as these factors influence management and outcomes (Figure 1).

1. Anatomical Site

-

Ileostomy: Diverts the ileum to the abdominal wall, commonly for IBD, familial adenomatous polyposis, or colorectal cancer.1 Outputs are typically liquid or semi-solid, and high-output ileostomies require strict fluid and nutritional management.2,8

-

Colostomy: Diverts the colon to the abdominal wall, often indicated in colorectal cancer, diverticulitis, or trauma.4 Sigmoid colostomies are the most common, produce formed stool which is easier to manage.3

2. Presentation

-

Emergency Stoma: Created for urgent cases (e.g., obstruction, perforation, trauma) with high complication risks. Usually temporary, with potential for reversal.5,7

-

Elective Stoma: Planned for surgeries (e.g., colorectal cancer) to protect distal anastomosis. Has lower complication rates due to controlled settings.6,9

3. Fate (Temporary vs. Permanent)

-

Temporary Stoma: Used to protect anastomoses, with reversal planned post-healing. In rectal cancer, temporary ileostomies reduce septic risks from anastomotic leaks.10,11 Timing of reversal is debated, with early closure reducing stoma-related complications but delayed closure ensuring better anastomosis healing.12

-

Permanent Stoma: Necessary when bowel continuity cannot be restored, such as after abdominoperineal resection or in end-stage Crohn’s disease.4,13

4. Construction (Loop vs. Divided)

-

Loop Stoma: Created by exteriorizing a bowel loop with two openings, the proximal for stool passage, and the distal for mucus drainage. Commonly used as a temporary measure, facilitating easy reversal. Frequently used in low anterior resection to protect anastomoses.6,14

-

Divided (Double-Barrel) Stoma: Features two separate openings without bowel continuity, minimizing obstruction risks in cases with distal lesions. Reversible without major laparotomy if the distal bowel is intact.14,15

-

End Stoma: Involves exteriorizing the proximal bowel end with the distal end closed off (Hartmann’s procedure) or removed, often permanent, especially in low rectal cancers with sphincter involvement.11,15

Each stoma type has specific management needs and risks. For instance, ileostomies require careful fluid/electrolyte management due to high output, while colostomies produce more manageable solid waste.16 Loop stomas, although easier to reverse, have higher prolapse rates.17

B. Complications of Stomas

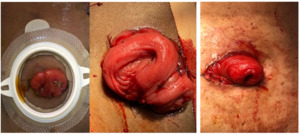

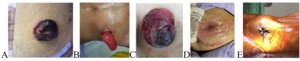

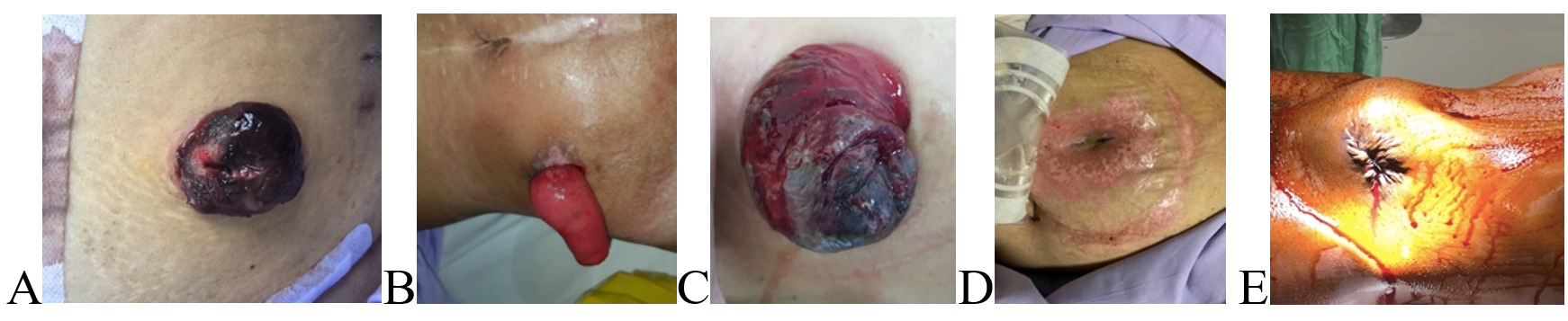

Stoma complications can arise early (within 30 days post-op) or later, sometimes years after surgery, with incidence rates ranging from 10% to 70% depending on stoma type, patient factors, and surgical expertise5 (Table 1). Effective management requires a multidisciplinary team, including surgeons and stoma nurses, for optimal outcomes (Figure 2).

Early Complications

-

Stoma Retraction: Occurs when the stoma pulls below skin level, due to low perfusion, bowel tension, or excess adipose tissue in obese patients.7 This can hinder appliance fitting and cause leaks, with severe cases necessitating revision surgery; convex appliances may suffice in mild cases.5,6

-

Ischemia and Necrosis: Inadequate blood supply can lead to ischemia and necrosis, appearing within days as dusky or black stoma.18 Risk factors include vascular disease, diabetes, and emergency stoma.4 Partial necrosis can be managed conservatively; full-thickness necrosis requires urgent revision.19

-

Stoma Edema: Edema is common post-operatively due to surgical manipulation. It usually resolves spontaneously but may obstruct output if severe, requiring larger-aperture appliances and potentially anti-inflammatory treatment.2,6,9

-

Mucocutaneous Separation: Separation of the stoma from the skin is more common in patients with poor healing due to malnutrition or steroid use.7 Minor separations may be managed with wound care, but significant separations need surgical intervention.5

-

Peristomal Skin Irritation: Affects up to 45% of patients due to stool or urine contact, causing dermatitis or burns.1,8 Prevention includes proper appliance fit and skin barriers, while existing irritation may require topical steroids or antifungals if infected.20

Late Complications

-

Parastomal Hernia: This occurs in 50% of colostomy patients when the intestine herniates around the stoma.21 Risk factors include obesity, age, and large stoma openings. Surgical repair options include local repair, relocation, or mesh placement, conservative management with support garments is also used.6,22

-

Stoma Prolapse: Seen in loop stomas, prolapse involves telescoping bowel through the stoma, causing discomfort, appliance issues, and ischemia if strangulated.23,24 Mild cases are managed with reduction and supportive appliances; severe prolapse requires surgical revision.25

-

Stenosis: Narrowing of the stoma, often seen in end stomas, can cause obstructive symptoms (bloating, nausea, difficulty passing stool).26,27 Dilators may be used in mild cases, while severe stenosis may need surgical intervention.28

-

Fistula Formation: Stoma-associated fistulas can result from infection, radiation, or recurrent disease, with enterocutaneous fistulas posing significant challenges due to stool leakage onto the skin.29,30 Management includes wound care, nutritional support, and potentially surgery.31

-

Psychological Impact: Up to 50% of stoma patients experience anxiety and depression, particularly younger patients and those with permanent stomas.32,33 Psychological support, counseling, and peer support are essential for improving quality of life.34

Stoma complications, whether early or late, require timely multidisciplinary intervention. Early issues like retraction, ischemia, and skin irritation necessitate prompt management, while late complications such as hernia, prolapse, and stenosis often need surgical revision. Early complication recognition, and patient education are key to optimizing outcomes.

C. Nutritional Support and Management for Stoma Patients

Nutritional management is essential for stoma patients, as nutrient, fluid, and electrolyte absorption can be significantly impaired depending on the affected bowel segment. Ileostomies pose greater challenges than colostomies, as they involve the small intestine, leading to notable fluid and electrolyte loss. Up to 80% of high-output ileostomy patients face major fluid/electrolyte losses, and about 30% require specialized nutritional support to prevent dehydration and malnutrition.35,36

Nutritional Impact by Stoma Type

-

Ileostomy: Ileostomy output is liquid to semi-liquid due to limited fluid absorption, with “high-output” ileostomies (>1.5 L/day) occurring in up to 25% of cases.37,38 This may lead to dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and deficiencies in vitamin B12, zinc, magnesium, and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K).39

-

Colostomy: Colostomy patients generally have fewer nutritional issues, as the colon continues to absorb water and electrolytes, resulting in more formed stools. However, significant colonic resection may lead to nutritional concerns, altered bowel habits, and constipation risk.40,41

Nutritional Guidelines for Stoma Patients

-

Hydration: Ileostomy patients should consume 2–2.5 L of fluids daily, potentially increasing to 3 L or more for high-output stomas.42,43 Oral rehydration solutions with sodium and glucose improve absorption.44

-

Electrolytes and Minerals: Sodium and potassium losses are significant for ileostomy patients, especially with outputs >1.2 L/day.45 Increased dietary sodium (soups, broths) and potassium (bananas, oranges) intake or supplementation is recommended and magnesium supplements are essential if diarrhea is chronic.46,47

-

Dietary Adjustments: Small, frequent meals help manage stoma output and nutrient absorption.48 Foods that increase output (high-fiber foods, raw vegetables, caffeine, alcohol) should be limited. Soluble fiber (from oats, bananas, apples) helps bulk stool and manage diarrhea, while starchy foods (potatoes, rice, pasta) thicken output.49–51

-

Protein and Caloric Needs: High-output stomas and post-operative recovery increase protein and calorie demands. Protein intake should be 1.5–2.0 g/kg/day, with adequate calories to avoid weight loss.52–54

-

Micronutrient Supplementation: Nutrient deficiencies, particularly vitamin B12 (30% of ileostomy patients) and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K), are common. B12 injections or high-dose oral supplements, along with continuous supplementation of fat-soluble vitamins, may be needed.55–57

-

Nutritional Support for High-Output Stomas: Enteral or parenteral nutrition may be necessary for high-output patients who struggle with hydration and nutrition via oral intake alone. Approximately 10–15% of high-output ileostomy patients may require temporary or permanent parenteral nutrition.58,59

Dietary Management of Specific Complications

-

Diarrhea and High Output: Medications like loperamide or codeine can slow intestinal transit, reducing losses. Diet adjustments, including soluble fiber increase and avoidance of trigger foods, are also crucial.60,61

-

Gas and Odor Control: Foods like beans, cabbage, and carbonated drinks increase gas production. Limiting these foods and using odor-control products in stoma appliances can help. Consuming yogurt, parsley, or cranberry juice may reduce odor naturally.62,63

-

Constipation: Often affecting colostomy patients, constipation can be managed by increasing fluid intake, high-fiber foods, and, in some cases, stool softeners.64,65

Nutritional support is vital for managing stoma-related challenges. Individualized care, including hydration, electrolyte balance, dietary modifications, and supplements, enhances patient outcomes and quality of life, especially for high-output stoma patients.

D. Psychological and Social Impacts of Living with a Stoma

Living with a stoma profoundly affects psychological and social well-being, impacting body image, emotional health, social interactions, and overall quality of life.

-

Body Image and Self-Esteem

Body image concerns are prevalent, with 50-70% of stoma patients reporting a negative change in self-perception, leading to decreased self-esteem and emotional distress. Women are particularly vulnerable to these issues. Over 50% of patients experience reduced sexual satisfaction post-surgery, reflecting the impact on intimate relationships.66,67

-

Emotional Impact

Anxiety and depression are common, affecting approximately 32% of stoma patients. Anxiety is heightened by lifestyle changes, fear of leakage, and social stigma. Leakage is a concern for 44% of patients, while complications like skin irritation and parastomal hernias contribute to distress for 30%.67,68

-

Social Isolation and Stigma

Social withdrawal is common, with 40% of patients reducing social interactions due to embarrassment, odor, leakage, or noise. Stigma is a significant factor in emotional distress, as evidenced by a Chinese study linking stigma with increased psychological distress.68–70

-

Quality of Life

Stoma-related complications, such as skin irritation and hernias, affect 56% of patients and worsen physical discomfort, reducing quality of life. A Brazilian study found that complications, particularly parastomal hernias, were prevalent in 47.4% of patients with colostomies or cancer-related stomas, which are associated with poorer quality of life.71

-

Self-Care and Support

Education and support are crucial for improving psychological and social outcomes. In one study, 90% of patients emphasized the importance of comprehensive preoperative and postoperative education, which boosted confidence, independence, and overall quality of life by reducing anxiety. Psychological counseling, peer support groups, and effective stoma management education are essential for fostering adaptation and enhancing quality of life.72

The psychological and social challenges associated with stomas highlight the need for a multidisciplinary approach involving education, counseling, and peer support to improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

E. Controversies in Stoma Management

Controversies in stoma management include timing for stoma reversal, choice between temporary and permanent stomas, appliance selection, and approaches to managing complications such as stoma prolapse, parastomal hernias, and peristomal skin issues.

-

Timing of Stoma Reversal

Timing of reversal for temporary stomas remains debated. While early reversal (6–8 weeks post-surgery) can enhance quality of life and reduce complication rates, it may also increase the risk of anastomotic leakage and other complications. Many practitioners favor delayed reversal, sometimes extending for several months, but evidence remains mixed.73,74

-

Permanent vs. Temporary Stomas

The decision between permanent and temporary stomas is often contentious. Temporary stomas, intended to protect distal anastomosis or as emergency interventions, become permanent in up to 30% of cases due to complications or poor recovery, raising ethical concerns about patient expectations and prolonged psychological distress.72,75

-

Stoma Appliances and Patient Satisfaction

There is no consensus on the optimal stoma appliance. Patient preferences vary widely, with some favoring lightweight, disposable options and others preferring durable, longer-lasting devices. A large-scale study found that 29% of patients were dissatisfied with their appliances, citing leakage, discomfort, and skin irritation as key issues.76

-

Management of Complications

Management of complications like stoma prolapse, parastomal hernias, and peristomal skin conditions lacks standardization. Parastomal hernias affect around 50% of stoma patients, with no clear consensus on preventive or corrective strategies. Some advocate prophylactic mesh placement, while others warn against it due to risks of infection and mesh erosion.77,78 Peristomal skin complications, affecting 35% of patients, also prompt debate over effective barrier creams and adhesives.79

F. Financial Impact of Stomas

The financial burden of living with an intestinal stoma is considerable, affecting both patients and healthcare systems due to costs associated with surgery, stoma care supplies, follow-up care, and complications management. This underscores the need for evidence-based guidelines and support mechanisms to improve patient outcomes and reduce the financial burden on both individuals and healthcare systems.

-

Initial Costs and Surgery

Stoma creation incurs high initial costs. In the U.S., stoma surgery costs range from $30,000 to $50,000, with similar figures reported in other developed nations, underscoring the substantial financial burden of these procedures.80,81

-

Ongoing Costs of Stoma Care

After surgery, patients incur ongoing expenses for stoma supplies, including bags, pouches, and skin barriers, amounting to $2,000 to $3,500 annually. In the UK, 76% of stoma patients report financial strain from these expenses. For healthcare systems, the annual cost of ostomy supplies can exceed $120 million in countries with universal healthcare.82,83

-

Complications and Healthcare Costs

Complications such as parastomal hernias, skin irritation, and stoma prolapses add significantly to healthcare costs. Around 50% of stoma patients develop parastomal hernias, with repair surgeries costing between $10,000 and $20,000. Skin complications require specialized care, adding further costs.72,84

-

Indirect Costs and Economic Burden

Indirect costs from lost productivity are substantial. Approximately 30% of stoma patients experience reduced work capacity or leave the workforce due to stoma-related health issues. In the UK, the estimated annual productivity loss from stoma complications is around £150 million.85,86

-

Insurance and Reimbursement Issues

Insurance coverage for stoma supplies varies widely, leading to significant out-of-pocket expenses for many patients. For uninsured or underinsured individuals, these costs can impair access to adequate stoma care, resulting in increased risk of complications.80

G. Key Findings of the Systematic Review on Intestinal Stoma Management

-

Stoma Appliance Selection?

Patients often experience dissatisfaction with stoma appliances, with 29% reporting issues related to leakage and discomfort. A propriate appliance choice and individualized care enhance patient comfort and stoma function.

-

Patient Education

Education and counseling significantly enhance patients’ ability to manage their stomas, with up to 90% of patients reporting improved confidence and quality of life after comprehensive care .

-

Parastomal Hernia

This is the most common complication,with incidence of 50% . While the use of prophylactic mesh during surgery reduces the risk of hernia, it remains debatable due to concerns about infection and technical challenges .

-

Peristomal Skin Issues

Skin complications are common, affecting 35% of patients. Long follow-ups and the use of skin barriers can mitigate these issues, but specialized care is essential for optimal outcomes

-

Timing of Stoma Reversal

Although early reversal improves quality of life but may increase complications, while delayed reversal reduces risks but prolongs the stoma duration. The optimal timing is still controversial.

-

Financial Impact

Stoma care presents a significant financial strain, with annual costs of appliances ranging from $2,000 to $3,500 per patient. Additionally, healthcare systems face high costs from stoma-related complications, highlighting the need for policy reform and better reimbursement models.

H. Clinical Implications

-

Patient-Tailored Care

Individualized stoma appliance selection and care routines tailored to patient needs can prevent complications like leakage and skin issues, improving the quality of life.

-

Prophylactic Mesh adoption

For high-risk patients, the use of prophylactic mesh during the procedure should be considered to reduce the parastomal hernias incidence.

-

Proper Follow-up plans

Regular follow-ups with specialized stoma teams are critical to preventing complications such as peristomal skin breakdown and stoma prolapse, ensuring better long-term outcomes.

-

Informed Surgical Decisions

The timing of stoma reversal should be individualized based on patient health, recovery, and risk factors, weighing the benefits of early reversal against the increased risks of complications.

-

Cost Management

The significant financial burden of stoma care underscores the need for improved healthcare policies,particularly regarding the reimbursement of stoma supplies and complications management.

I. Conclusions

Effective management of intestinal stomas is essential to enhance patient quality of life, reduce complications, and manage healthcare costs. A patient-centered approach with continuous follow-up, policy improvements, and further research will enhance stoma management and patient outcomes. Key improvement areas include:

-

Customized Appliance Selection and Education: Tailored stoma appliances and proper patient education reduce issues like leakage and skin complications, improving patient satisfaction and quality of life.

-

Complication Prevention: Proactive measures, such as prophylactic mesh for hernias and specialized skin care, are essential to prevent parastomal hernias, peristomal skin problems, and stoma prolapse.

-

Clinical Controversies: Decisions around stoma reversal and prophylactic strategies, including mesh use, require individualized risk-benefit assessments to optimize outcomes.

-

Financial and Nutritional Considerations: High costs and complex nutritional needs necessitate individualized care, policy improvements. Tailored dietary support is essential to address dehydration and malabsorption.