INTRODUCTION

The Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) sets the emergency medicine (EM) residency program requirements. One requirement is that the residency must provide evaluation and feedback from multiple evaluators, including faculty members, fellow residents, medical students, patients, nursing staff and other professional staff members.1 Multisource feedback (MSF) or 360-degree assessments are defined as the “evaluation of a person by multiple individuals that have different working relationships with the person, through use of questionnaires and a compiled feedback report”,2 as well as a self-evaluation of the individual. MSF has been shown to be a reliable and feasible assessment tool to evaluate physicians across various specialties.3

LaMantia et al. specifically looked at creating an MSF and implementing it as a tool to evaluate competencies for EM residents. They concluded that although feasible, it was challenging due to this evaluation being resource intensive.4 Garra, Wachket and Thode also examined the feasibility of an MSF tool for EM resident and also concluded that although feasible it required a large number of completed evaluations to be reliable.5 Despite its complexity to complete, EM residents have found that multisource feedback assessments are relevant, useful and well received.6 It was also found to have a profound impact on the patient-physician relationship and specifically addressed the competencies of professionalism and interpersonal communication skills.6

Direct observation of resident’s patient encounters and their individual performance is an essential aspect of competency-based education.7 Yet a systematic review which examined the types and frequency of resident assessments, found that direct observation was used a quarter of the time.8 Documented barriers to direct observation which include the expectation that the resident should initiate the direct observation moment, social demands of not “burdening” faculty, lack of faculty time and availability9 and cost.10 Despite the barriers, direct observation positively affects resident’s knowledge, skills and attitudes.11 In 2009, Dorfsman and Wolfson concluded that implementing a structured direct observation program is well received by residents and faculty and can provide information about resident’s strengths and weaknesses as individuals and as a group.12 Despite its challenges, direct observation is a key component to clinical teaching and evaluation. Hauer describes twelve steps for selecting and incorporating direct observation of clinical trainees.13 These 12 steps included determining which competencies would guide the tool for direct observation, deciding if this tool would be formative or summative assessment, identifying an existing tool for direct observation and then creating a culture that values direct observation. It is important to conduct faculty development on direct observation both about the tool itself but also on how to best give feedback. It is also mentioned that it is crucial to orient learners to the direct observation and feedback that they will be receiving.13 Using this framework, we developed the educational innovation described below.

As a community EM residency program, our residents were required to complete at least one 360-degree assessment every quarter. Over the years, we observed that residents were not committed to completing these assessments. Acknowledging the importance of 360-degree assessments, the residency program sought ways to increase the resident’s willingness to complete these evaluations and engage the faculty in delivering more concrete feedback as well. It was also noted that while direct observation of resident’s patient encounters occurred, the formative evaluation process was deficient. The EM faculty acknowledged that direct observation with a completed formative evaluation would be ideal. To facilitate MSF and enhance resident education, direct observation teaching shifts (DOTS) were created. DOTS were defined as scheduled shifts in which paired faculty/residents were assigned a chief complaint-based patient encounter and the 360-degree assessment was used as the evaluation tool

This was presented as a poster at the 2021 CORD EM Scientific Assembly (Virtual) on April 14, 2021.

METHODS (Innovation/CURRICULAR DESIGN)

Objective of educational innovation

The objective of this educational innovation was to assess the resident’s perceptions and number of timely completed 360 evaluations after the introduction of DOTS. We hypothesize that the implementation of DOTS will increase the number of 360-degree evaluations completed by EM residents during their EM rotation. The second objective was to use direct observation to engage the supervising physician in creating educational opportunities and timely feedback.

Design of educational innovation

Using the ABEM Model of Practice of 2016,14 DOTS were assigned a specific sign or symptom categorized as “critical.” Signs, symptoms, and presentations identified as “critical” were matched to reference textbook chapters for reading and studying purposes. (Appendix A). Each 4 week block was assigned two distinct topics. Over a 12-week period, residents that were scheduled to the EM rotation were assigned DOTS paired with a designated faculty member. Specific lower volume shifts were chosen to maximize educational opportunities – morning and overnight shifts. All 18 residents had the opportunity to have at least 1 DOTS. The designated EM faculty members were given a brief faculty development session about the 360-degree assessments, best practices on clinical teaching and feedback during a monthly faculty meeting. (Appendix B) At the completion of the 12-week period, residents and faculty were surveyed using Microsoft Forms and data was extracted and analyzed using Microsoft Excel. (Appendix C and D)

RESULTS

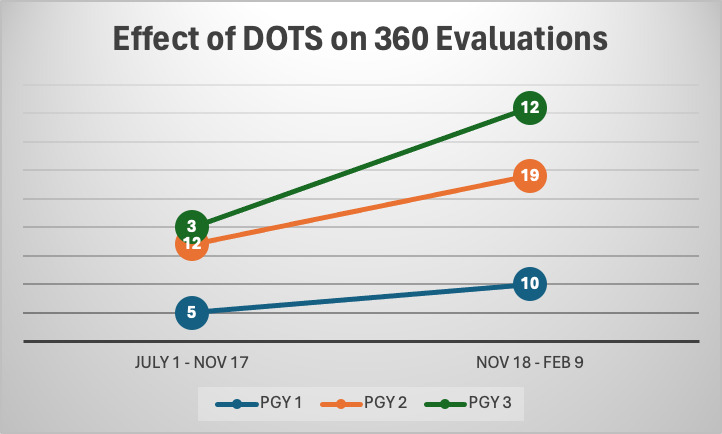

After completing the 12-week period, the number of 360 evaluations more than tripled per week. (Table 1 and Graph 1) At least half of the PGY 1 (3 of 6 residents), five out of six PGY2 and all six of the PGY3 had at least 2 DOTS. We had a 67% resident response rate for the survey about DOTS. Most of the residents that were scheduled a DOTS completed a 360 evaluation (67%) and felt that they received individualized learning (83%) from the attending. Although only half of the residents prepared for the DOTS by reading, almost all the residents felt they learned something during the DOTS but at times they were difficult to complete due to being chief complaint based. The majority (75%) said that they would like to continue to be scheduled DOTS. Residents and faculty were surveyed to provide feedback on DOTS. Table 2 illustrates the comments given by residents and attendings about the advantages and disadvantages of DOTS.

Direct observation teaching shifts were only supervised by 5 designated EM faculty. We had a 100% attending response rate for the survey, about the DOTS, and the principal investigator was excluded from the survey. All the attendings believe that we should continue completing the DOTS and involve more attendings. The best shifts would be the 6am and the 9pm shifts.

DISCUSSION

The implementation of DOTS significantly impacted the completion and perceived value of 360-degree evaluations within our program. The structured approach to integrating direct observation and multisource feedback aimed to address several critical aspects of competency-based education.

The introduction of DOTS led to a substantial increase in the number of completed 360-degree evaluations. The more than tripling of evaluations per week suggests that the structured nature of DOTS and the pairing of residents with designated faculty members during specific shifts facilitated the evaluation process. This increase not only reflects improved adherence to program requirements but also indicates a higher engagement level from residents in their educational process.

The positive feedback from residents highlights the educational value of DOTS. A significant proportion of residents reported receiving individualized learning and feedback, which is essential for their professional development. This finding underscores the importance of direct observation in clinical teaching, as it provides residents with targeted feedback on their clinical skills, professionalism, and interpersonal communication. The feedback from residents also indicated that despite the challenges of preparing for DOTS, the sessions were perceived as valuable learning opportunities.

The 100% response rate from faculty members and their unanimous support for continuing DOTS demonstrates strong faculty engagement. Faculty development sessions focused on 360-degree assessments and best practices in clinical teaching likely contributed to this high level of engagement. Faculty members recognized the educational benefits of DOTS and supported the expansion of the program to include more attending physicians. This support is crucial for the sustainability and further development of the program.

Despite the overall success, several challenges were identified. Residents noted that preparing for DOTS could be demanding, especially given the chief complaint-based structure. Additionally, the reliance on a limited number of faculty members to supervise DOTS may have constrained the program’s scalability. These challenges highlight the need for continuous refinement of the DOTS structure and the potential expansion of faculty involvement to distribute the workload more evenly.

The results of this innovation align with the broader goals of competency-based medical education (CBME), which emphasize direct observation and multisource feedback as key components.15 The successful implementation of DOTS demonstrates that structured direct observation can enhance the assessment process, providing valuable insights into resident competencies. Furthermore, the program’s ability to engage residents and faculty in meaningful educational activities supports the ongoing development of a culture that values direct observation and feedback.

Moving forward, several steps can be taken to build on the success of DOTS. Expanding the pool of faculty members involved in DOTS and providing ongoing faculty development will be crucial. Additionally, exploring ways to integrate DOTS into higher volume shifts without compromising the quality of education can help address some of the logistical challenges. Continuous evaluation and feedback from both residents and faculty will be essential to refine the program and ensure it meets the evolving needs of the residency program.

LIMITATIONS

While the implementation of Direct Observation Teaching Shifts (DOTS) has shown results, several limitations must be acknowledged. DOTS relied heavily on a small group of five designated EM faculty members. This limited pool of faculty might not represent the broader faculty population, potentially impacting the generalizability of the findings. DOTS were designed around chief complaint-based patient encounters, which some residents found difficult to complete. This structure may not cover the full spectrum of competencies and clinical scenarios that residents encounter, potentially limiting the breadth of their assessment and learning experiences. Only half of the residents prepared for their DOTS by reading the assigned material. This lack of preparation could affect the quality of the learning experience and the feedback received. The resident response rate for the survey about DOTS was 67% ( This gap could mean that the data might not fully capture all residents’ perceptions and experiences with the DOTS program. DOTS were scheduled during specific lower-volume shifts (morning and overnight). While this was done to maximize educational opportunities, it might not reflect the full range of clinical pressures and environments that residents face. Implementing and sustaining DOTS required significant resources, including time and effort from faculty for direct observation, feedback, and faculty development sessions. The resource-intensive nature might pose challenges for scalability and long-term sustainability. The education innovation was conducted within a single community EM residency program, which might limit the generalizability of the findings to other residency programs with different settings, resources, and structures. Multi-center studies or larger-scale implementations would be necessary to validate the findings across diverse settings. Addressing these limitations in future iterations of the DOTS and in similar educational innovations can help enhance their effectiveness, scalability, and generalizability, ultimately contributing to improved competency-based medical education for EM residents.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the implementation of DOTS has proven to be an effective educational innovation, enhancing the completion of 360-degree evaluations and providing valuable learning opportunities for EM residents. The positive feedback from both residents and faculty underscores the program’s potential to contribute significantly to competency-based education in emergency medicine.