INTRODUCTION

Paraduodenal hernias (PDHs) are rare but the most common type of congenital internal peritoneal recess hernia.1 Of the 0.6-5.8% of reported cases of internal hernias, PDH accounts for 53%.2 PDH is divided into two subgroups, namely, right PDH and left PDH, with the left being the more common form, also known as Landzert’s hernia.1–3 Regarding gender, internal hernias affect men three times more frequently than women.4

Radiologists and clinicians are challenged by internal hernias due to their rarity and the complexity of their diagnosis and treatment.5 The clinical presentation includes chronic non-specific symptoms such as chronic abdominal pain, constipation, and indigestion over time, posing a diagnostic challenge and leading to more acute presentations, such as acute intestinal obstruction, or a more grave presentation, such as intestinal ischaemia and perforation and its sequelae if untreated.2,6

Preoperatively, timely diagnosis is often difficult, leading to grave consequences and a reported mortality rate of more than 20%.2 Medical history, clinical examination, laboratory diagnostics, and preoperative CT scan contribute to the diagnosis. Despite the stated diagnostic possibilities, the final diagnosis is usually made during surgery.6 The ultimate modality of treatment is operative repair, either laparoscopic or open repair, depending on the operative facilities and level of expertise available.3,6 Laparoscopic surgery has a quicker recovery period, although both procedures have comparable long-term results.7

In this article, we present a case of a left PDH in a 14-year-old boy who arrived at the hospital complaining of severe abdominal pain for the past week that had been exaggerated in the last two days. The main objective of this report is to increase awareness of the likelihood of PDHs as one of the causes of intestinal obstruction.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 14-year-old male patient was admitted to a surgical casualty ward with a 1-week history of abdominal pain and worsening of pain for a 2-day duration, which is associated with frequent episodes of non-bilious vomiting. He denies any difficulty in opening the bowel. Up on further questioning, he was seen by a local doctor and prescribed some anti-emetics and phosphate enema, but he denied any remarkable clinical improvement. He has no other comorbidities, and the rest of the history was unremarkable.

On examination, he was ill-looking and dehydrated, with a pulse rate of 110 beats per minute and a blood pressure of 80/50 mmHg. He was febrile and running the temperature of 39 degrees Celsius. Abdominal examination revealed a distended and diffusely tender abdomen with sluggish bowel sounds. Laboratory blood investigations were all normal. An erect X-ray of the abdomen showed few dilated small bowel loops predominantly occupying the left hypochondrial region. A computed tomography scan of the abdomen demonstrated sac-like clustered small bowel loops noted in the left upper quadrant, in the anterior pararenal space, consistent with the diagnosis of left paraduodenal hernia.

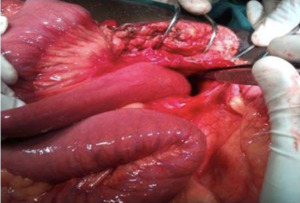

Although his urine output improved with resuscitation, his bowel functions did not improve even after 48 hours of resuscitation and treatment. Two days after initial presentation, an exploratory laparotomy was performed due to the patient’s complex and unpredictable condition. The laparotomy revealed serous peritoneal fluid and massively distended jejunal loops surrounded by the peritoneal sac and involving the entire abdomen. There was no evidence of peritoneal spillage. The left paraduodenal region was found to be covered by a retrocolic collection of small bowel loops encased within the hernial sac to the left of the third part of the duodenum (Figures 3, 4).

Further survey showed that the proximal jejunum had herniated into the mesenteric sac through a narrow neck, with almost the entire jejunal loop being hemorrhagic but viable with demonstratable peristalsis. After reducing the hernial contents, the hernial sac was wide opened to ensure that there is no potential site for internal hernia. Then routine midline closure was done with loop nylon. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and he was able to tolerate oral fluids and open his bowels on the second postoperative day. Postoperative laboratory investigations were normal, and he was discharged on the fourth postoperative day in good condition. He is being followed up to ensure that the surgical wound had healed and that there were no complications after the procedure.

DISCUSSION

Internal hernias comprise organ protrusion through a multitude of defects, i.e., normal (foramen of Winslow), paranormal (for instance, the paraduodenal fossa), and abnormal (through a trans-mesenteric, trans-peritoneal, or trans-omental defect). These defects may be congenital due to intestinal malrotation or the absence of retroperitoneal attachments or acquired due to past abdominal surgery, trauma, or any ischaemic process.6 Schizas et al. stated that PDH typically develops between the ages of 40 and 60, while Muneer et al. reported that PDH typically develops at a mean age of 44.1 years.4 Men experience PDHs three times more frequently than women.5

The diagnosis of PDHs is the most challenging aspect of management. This is because of the non-specific presentation of PDH. Presenting symptoms can range from diffuse abdominal pain that is frequently eased by positional modifications to acute intestinal obstruction, which is the most common presentation.8 A contrast CT scan of the abdomen plays a crucial role (sensitivity: 95-100%, specificity: 95%) and, in most cases, confirms the diagnosis.9 This is in addition to a thorough medical history, a clinical examination of the patient, an abdominal X-ray, an abdominal ultrasound, and laboratory tests.9

The importance of CT in the early preoperative identification of PDH is justified by the significant death rate associated with these complications.10 The typical CT finding is a mass of dilated small intestinal loops arranged abnormally between the stomach and pancreas to the left of the Trietz ligament. The transverse colon, the duodenal flexure, and the posterior wall of the stomach are frequently displaced due to a mass effect. At the entry of the hernial sac, the mesenteric arteries supplying the herniated small bowel seem congested, engorged, and stretched.11,12

The ultimate modality of treatment is operative repair, either laparoscopic or open repair, depending on the operative facilities and level of competency available.1,3,6 There is considerable debate regarding whether to perform a laparoscopy or a laparotomy. The literature does, however, demonstrate that laparoscopic repair of a PDH can reduce hospital stay, encourage early eating, and lower the likelihood of perioperative problems.13,14 Patients with PDH have a 20-50% mortality rate for acute presentations; hence, early surgical intervention is crucial to prevent subsequent problems. In this case, we have intervened promptly due to the fact that morbidity is lower.

CONCLUSIONS

This case report highlights the importance of early and accurate diagnosis of left PDHs, which can be life-threatening if not detected and treated promptly. The findings of this study demonstrate the necessity of a thorough physical examination and prompt imaging in patients with a history of recurrent abdominal pain and no prior abdominal surgeries.

The successful treatment of this patient through laparotomy, followed by reduction of herniated bowel loop and widening of herniated sac, emphasises the critical role of surgical intervention in such cases. This case report contributes to the existing literature on PDHs and provides valuable insights into the diagnosis and management of this rare condition.