Introduction & Background

Early Life

Born in July of 1933 in his family home in Aleppo, Syria, Dr. Mohammad Walid Sankari, the oldest of four children, was raised by his father, a farmer, and his mother, a home-maker. With his only connection to the medical field being an uncle who was a pharmacist and another uncle who was a physician for the Syrian military, Dr. Sankari’s legacy in medicine seemed almost unprecedented with such humble beginnings.

Early Medical Years

Dr. Sankari graduated from the University of Damascus Medical School in 1958, which was the only university in Syria at the time, and one of the oldest medical schools in the Middle East.1 Because Syrian hospitals lacked medical residency programs at the time, Dr. Sankari chose to continue his education in Paris, where his fluency in French, acquired during the French occupation of Syria that lasted until 1946, proved essential. In 1960, Dr. Sankari, along with his wife, Zabia-who would go on to be an English professor at the University of Aleppo’s Dental School-found himself in Paris, specializing in pulmonary disease at the renowned Laennec Hospital (Figure 1). His time in Paris was transformative, as he deepened his knowledge and honed his skills in a specialty that would define his career. Upon his return to Syria in 1965, Dr. Sankari brought with him a wealth of knowledge and a vision to revolutionize pulmonary care in his homeland, particularly in the fight against tuberculosis (TB), a disease that was-and remains-highly prevalent in Syria and the broader Middle Eastern region.

Review

Father of Tuberculosis

Dr. Sankari’s work in tuberculosis was nothing short of pioneering. In 1966, he was instrumental in establishing Aleppo’s first and only TB Control Center, and a TB Control Association, in Syria. Dr. Sankari’s initiatives were particularly impactful in rural areas, where healthcare resources were scarce and TB was rampant. Dr. Sankari published extensive data on TB and presented his findings at international conferences. His work not only raised awareness about TB in Syria, but also played a critical role in destigmatizing the disease amongst local communities, educating the public on symptoms such as coughing blood, and promoting national protocols for treatment.

While the data on the prevalence of TB in Syria from this time is undocumented, it is because of Dr. Sankari’s efforts with the TB Control Center that TB cases in Syria fell from 85 cases per 100,000 persons in 1990, to 6 cases per 100,000 persons in 2010.2,3 His contributions earned him the affectionate nickname “Walid Abu-Sil” or “the father of TB,” reflecting the deep respect and admiration he garnered for his relentless efforts in combating the disease (Figure 2).

University of Aleppo Medical School

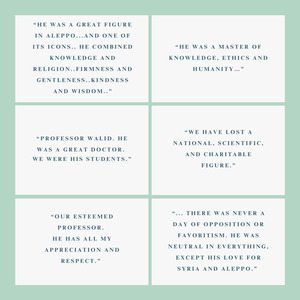

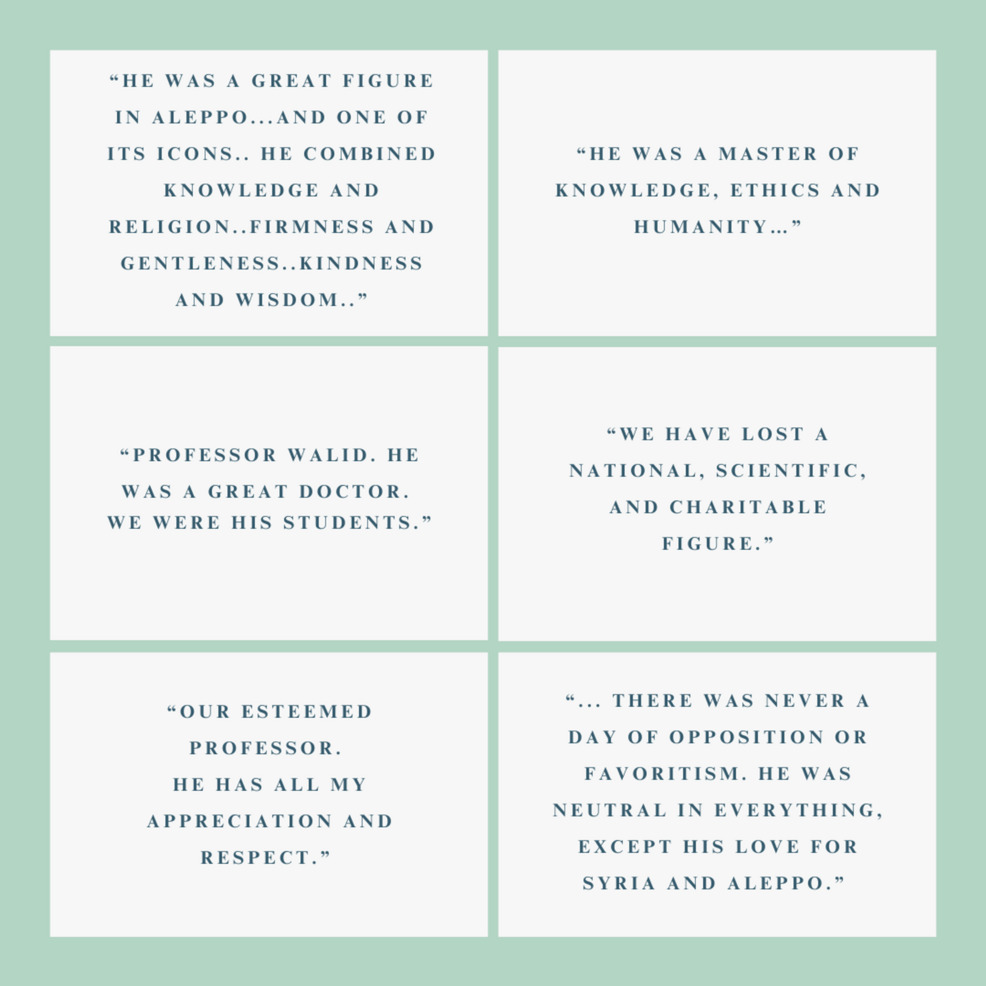

Dr. Sankari served as a professor of pulmonology at the University of Aleppo’s medical school from its inception in 1967 until the late 1990s (Figure 4). His influence on the university and its students was profound; impacting multiple generations of Syrian physicians. Dr. Sankari was more than a professor; he was a mentor and a friend, “a great figure in Aleppo, and one of its icons; he combined knowledge and religion, firmness and gentleness, kindness and wisdom” (Figure 5).4 To this day, his legacy continues to resonate through the countless lives he touched, both within and beyond the walls of the university.

Syrian Arab Red Crescent

The Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC), originally founded in Damascus, Syria, in 1942, is a humanitarian organization in Syria that provides emergency relief, medical services, and community support. In the early 1980s, Dr. Sankari became the Chairman of the Aleppo branch of the SARC, alongside his close friend Dr. Nizar Hampsi. Upon becoming a leader of the branch, Dr. Hampsi was assassinated by anarchist radical groups opposed to the organization, as they saw the SARC as another arm of the government. Despite these challenges and the countless death threats that Dr. Sankari received from these groups, he remained steadfast in his commitment to humanitarian work. His leadership in the SARC was pivotal during the Iraq war in the early 2000s, helping hundreds of thousands of refugees gain access to healthcare and vital resources.5

The Syrian Civil War began in 2011, as the Syrian government used violence to suppress protesting groups from expressing widespread dissatisfaction with the regime and demands for democratic reform.6 The conflict quickly evolved into a complex struggle, leading to significant humanitarian crises and massive displacement. By 2012, the conflict had expanded into a full-fledged war between the Syrian government and its people. Despite the danger, Dr. Sankari saw to it that his own people were not forgotten. He worked tirelessly to bring medicine, clean water, and baby formula to those in need.

Even while focusing his efforts on the SARC, Dr. Sankari’s work with Tuberculosis was never finished. As the war raged on, TB cases quickly rose back up to 23 cases per 100,000 persons in 2011. Additionally, after a destructive conflict in 2016, the TB Control Center was forced to shut its doors. However, Dr. Sankari, with the financial help of the Japanese government, was able to see the TB Control Center reopen its doors in 2018 - cases were brought back down to 18 cases per 100, 000 persons in 2018.7

Despite the immense challenges that Dr. Sankari faced as a leader of the SARC branch in Aleppo, including the ongoing civil war and its unpredictable nature, he never failed to recognize the critical role of those who supported his efforts. He advocated for, and emphasized the importance of every member of the SARC. “Volunteers are risking their lives to help people in need. The least we should do is provide them the proper training and the financial support to help them commute,” he remarked in a 2015 speech.8 Dr. Sankari’s leadership was marked by his unwavering commitment to both the cause and the people who made it possible.

Long-Lasting Syrian Legacy

Throughout his career, Dr. Sankari continued to practice pulmonary medicine in his private clinic, often seeing patients without charging those who couldn’t afford to pay, as he believed in the human right to receive healthcare. His generosity earned him the reverent nickname “Jesus” around Aleppo, symbolizing the profound respect and love the community had for him. His legacy is enshrined in Syria, with a wing in the Pulmonary Hospital and a wing in the Children’s Hospital bearing his name, and his portrait still adorn the walls of the University of Aleppo (Figure 5).9 In a country and region where healthcare challenges remain significant, Dr. Sankari’s work serves as a beacon of hope and a model for future generations. His legacy is not just one of medical achievement but of humanity, compassion, and the relentless pursuit of a healthier world.

Dr. Mohammad Walid Sankari passed away in December of 2023, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire. As one former student stated, “We have lost a national, scientific, and charitable figure,” (Figure 4). His life was a testament to the power of dedication, compassion, and innovation in medicine. Dr. Sankari’s contributions to pulmonary medicine, particularly in the fight against TB, and his humanitarian work with SARC, have left an enduring impact on the Syrian community and the broader medical field. His story is one of resilience, commitment, and an unwavering belief in the right to free access to healthcare for all.

Conclusion

Dr. Mohammad Walid Sankari’s life and career are a testament to his extraordinary contributions to medical excellence and humanitarianism. With deep expertise in pulmonary medicine, he has played a pivotal role in combating tuberculosis, a disease that continues to afflict vulnerable populations in Syria and beyond. Through the development of treatment protocols and preventive measures, his work has saved countless lives and significantly raised the standard of care in the region. Dr. Sankari’s influence extends beyond individual patient care; he laid the groundwork for public health initiatives that address not only tuberculosis but a range of respiratory illnesses, establishing a lasting impact on healthcare systems in areas of critical need.

As a professor and leader, Dr. Sankari dedicated his career to mentoring and educating generations of physicians, many of whom have become prominent figures in healthcare. His influence in academia shaped medical training and equipped doctors with the tools to face complex medical challenges in resource-limited settings. Beyond education, his leadership was crucial in establishing vital healthcare infrastructures, including the Aleppo TB Control Center and the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, which provided critical care and humanitarian aid during crises. These contributions underscore the importance of building strong public health systems and ensuring that healthcare professionals are well-prepared to meet the needs of underserved communities, a lesson highly relevant in today’s global healthcare landscape.

Dr. Sankari’s unwavering dedication to serving the underprivileged, often at great personal risk, demonstrates his belief in healthcare as a fundamental human right. His work in conflict zones and remote areas highlights the ethical responsibility of ensuring equitable healthcare access, especially in regions impacted by conflict and limited resources. His legacy as a compassionate healer and advocate for the underserved continues to inspire future generations to pursue healthcare not only as a profession but as a means of promoting justice and equity. In a world still grappling with infectious diseases and healthcare disparities, Dr. Sankari’s life work is more relevant than ever, offering a powerful model for addressing modern healthcare challenges with resilience, innovation, and empathy.