Introduction

Beriberi, a condition caused by thiamine deficiency, is most commonly linked to chronic alcoholism but can also result from severe malnutrition.1–3 The disease presents in two major forms: Dry beriberi, which manifests as peripheral neuropathy and acute encephalopathy, with severity proportional to the degree and duration of thiamine deficiency, and wet beriberi, which is characterized by right-sided heart failure symptoms, such as dyspnea and peripheral edema.2,4 Shoshin beriberi is a rare but fulminant form that can lead to cardiovascular collapse, progressing rapidly to multi-organ failure with high mortality.1–5 It is marked by peripheral cyanosis, hypotension, renal failure, and severe metabolic acidosis.2 Thiamine plays a crucial role in metabolic processes as a precursor of the cofactor thiamine pyrophosphate, which is involved in several key steps in carbohydrate metabolism, including the Krebs cycle. The resulting lactic acidosis arises due to impaired aerobic metabolism caused by thiamine deficiency, leading to an accumulation of substrates like pyruvate and lactate as anaerobic pathways are activated.2,4–6 Due to its rapid and severe clinical presentation and the absence of rapid diagnostic tests, shoshin beriberi is often underdiagnosed, especially in non-alcoholic patients.2 Here, we present a case of shoshin beriberi associated with non-specific hyperamylasemia, occurring under different circumstances of thiamine deficiency.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old female with a medical history of arterial hypertension was diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the cardia. She underwent neoadjuvant therapy followed by a total gastrectomy and distal esophagectomy via laparoscopy and thoracoscopy. Postoperatively, the patient developed an esophagojejunal anastomotic leak, which was treated endoscopically with a metallic stent. Adequate nutritional support, including enteral nutrition and proper vitamin supplementation, was provided.

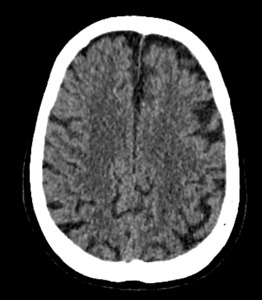

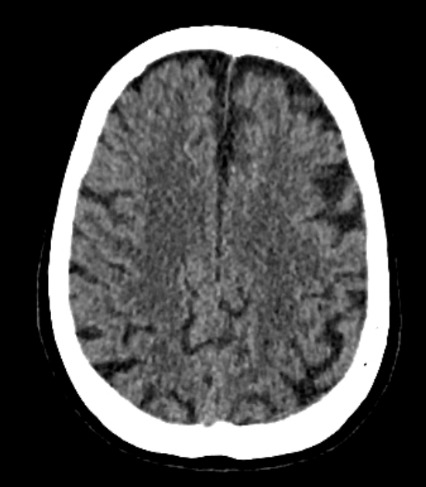

Four months after surgery, she presented to the emergency department due to the onset of motor skill disturbances, prompting evaluation by the neurology department. A cranial CT scan suggested the possibility of a subacute ischemic stroke affecting multiple territories (Figure 1). Further investigation revealed that the patient had visited her primary care physician two months before admission, reporting food intolerance, anorexia and weight loss.

Three days after hospitalization, the patient developed an altered level of consciousness along with symptoms of polypnea (28 breaths/min), oxygen saturation of 87% on room air, tachycardia at 155 beats/min, and hypotension (85/55 mmHg). Tympanic temperature was 36.6°C. On examination, she appeared cachectic. Capillary refill time was over 3 seconds, and jugular venous distension was noted, but heart and respiratory sounds were unremarkable. The abdomen was soft and non-tender, with no organomegaly. Neurological examination revealed reduced muscle strength in both lower limbs and cognitive impairment. Hemodynamic monitoring indicated cardiogenic shock, and resuscitation was initiated immediately. Given her clinical presentation, a pulmonary embolism was initially suspected. However, a contrast-enhanced chest CT scan ruled out a pulmonary embolism.

Echocardiography revealed a dilated left ventricle with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction of 56%, without regional wall motion abnormalities. A repeat cranioencephalic CT was unremarkable. Arterial blood gas analysis indicated significant lactic acidosis, and blood tests showed isolated hyperamylasemia at 3540 units/liter. The infectious workup was negative. Abdominal ultrasound revealed liver congestion, along with dilatation of the inferior vena cava and suprahepatic veins. An abdominal CT scan, followed by exploratory laparotomy, did not reveal signs of acute pancreatitis or any other medical condition.

In the intensive care unit, the patient required intubation due to increased work of breathing and potential respiratory fatigue. Despite fluid resuscitation and vasopressor therapy, she remained hemodynamically unstable. Metabolic acidosis persisted, despite frequent sodium bicarbonate administration. The patient died later that day.

Discussion

Beriberi was first documented by Aalsmeer and Wenkebach in Asia in 1929. By the 1960s, the prevalence of the disease had decreased, primarily due to improved nutrition and public health campaigns. Although now rare in developed countries, beriberi still occurs in individuals with poor nutritional intake, such as those who consume excessive alcohol, follow extreme diets, or in the elderly.3,4

Shoshin beriberi is an easily treatable condition that can mimic other life-threatening illness like sepsis or heart failure. Despite its rarity in Western countries, beriberi has not been fully eradicated and can go undiagnosed where its prevalence is low. Clinicians should therefore maintain a heightened level of suspicion when faced with severe metabolic acidosis and refractory hemodynamic collapse, particularly if the patient has any risk factors for thiamine deficiency.2,4,6,7

The present case report of presumed shoshin beriberi aims to highlight the emergence of additional causes of thiamine deficiency in the modern world, especially those linked to esophagogastric surgery, which carries a substantial risk of malnutrition in the medium to long term. Several studies have documented the association between upper gastrointestinal surgery and complications related to thiamine deficiency.8–10 Thiamine deficiency can develop between 8 and 15 weeks post-surgery, though some cases have been reported as early as 6 weeks. Even with oral supplementation, deficiency may still occur if vomiting is present, as it impairs proper absorption. In outpatient care, regular monitoring of key micronutrients every 3 to 6 months after esophagogastric surgery can help identify deficiencies before they become symptomatic.9 In critical care, since thiamine is not routinely administered, it is vital to maintain a high index of suspicion in patients at high risk for nutritional deficiency.

Conclusion

We advocate for the inclusion of thiamine in the ‘coma cocktail’ for managing all patients with altered consciousness in emergency or intensive care units. The timely administration of thiamine is generally safe and can result in rapid improvement, making it both a valuable therapeutic and diagnostic tool.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and it is cleared by my institutional ethics committee.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.