INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a potential adverse effect of ticagrelor, an antiplatelet medication commonly used in patients with acute coronary syndrome or a history of heart attack or stroke.1 While ticagrelor is effective in preventing cardiovascular events, it is essential for clinicians to be aware of this potential complication and manage it appropriately.

Ticagrelor, consumed orally, inhibits platelet aggregation via reversible binding of the P2Y12 receptor and serves as an antagonist to prevent platelet activation and aggregation induced by adenosine diphosphate.2,3 Ticagrelor acts rapidly due to its ability to function without an active metabolite.1,4 In this way, ticagrelor differs from clopidogrel, a popular antiplatelet drug, which is irreversibly bound to the P2Y12 receptor and requires an active metabolite to function.1,4

The incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding with ticagrelor is relatively low but can occur.1 Patients at higher risk for gastrointestinal bleeding include those with a history of peptic ulcer disease, previous gastrointestinal bleeding, or concomitant use of anticoagulant medications or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.5 Advanced age and renal impairment may also increase the risk.1 The authors present the case of an octogenarian who presented with dark stools while on the medication.

CASE PRESENTATION

A male in his 80s presented to the Emergency Department (ED) due to black stools and fatigue. He had cardiac stents placed a few months prior and was discharged home on aspirin and clopidogrel. On routine cardiology follow-up, P2Y12 platelet function testing suggested resistance to Clopidogrel, and he was then switched to ticagrelor. A few weeks after being on ticagrelor, he developed black stools and extreme tiredness. At baseline, he was an extremely active octogenarian who was playing 9 holes of golf daily. Past medical history was significant for coronary artery disease status post coronary artery bypass graft 40 years and 20 years prior, coronary stents, Barrett’s esophagus, hypertriglyceridemia, and mild hypertension. The patient was on daily aspirin, ticagrelor, esomeprazole, metoprolol, and atorvastatin.

In the ED, his vital signs were: temperature 98.7oF, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, pulse 77 beats per minute, oxygen saturation 100% on room air, and blood pressure 159/92 mmHg. His hemoglobin was found to be 8.5 g/dL. Chest radiograph revealed cardiomegaly with bilateral central pulmonary vascular congestion. The patient was advised to discontinue the ticagrelor temporarily and follow up with his cardiologist.

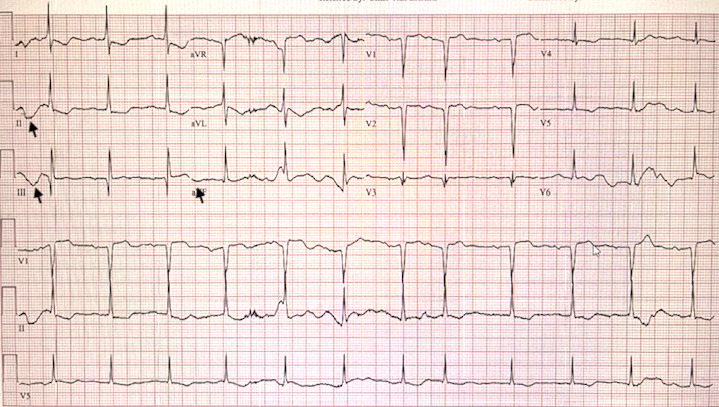

Five days later, his fatigue became so pronounced he could barely walk from his bed to his bathroom (approximately 10 feet without feeling lightheaded), so he came back to the ED. This time his vital signs demonstrated marked tachypnea with increased work of breathing, a temperature of 98.2oF, respiratory rate of 29 breaths per minute, pulse of 69 beats per minute, oxygen saturation of 98% on room air, and blood pressure of 160/91 mmHg. The relative lack of tachycardia could be attributed to his compliance with daily metoprolol. Given his complaint of dyspnea, a cardiac workup was performed. EKG revealed inferolateral ischemia, with inverted T waves in leads II, III, and AVF (Figure 1).

Troponins were elevated at 780 ng/L initially and then 892 ng/L two hours post ED arrival. The hemoglobin was low at 8.5 g/dL [Table 1]. This was presumed to be due to GI bleeding from the antiplatelet agent. The patient was transfused with 2 units of packed red blood cells, following which he felt significantly better. His tachypnea resolved, and his EKG normalized.

He was discharged home with outpatient gastroenterology follow-up. The patient’s cardiologist recommended he discontinue the ticagrelor altogether and go back to his clopidogrel regimen, which had been working well for him. Three weeks later, the patient had an endoscopy, which revealed no active sources of bleeding. A large sessile polyp was removed. Two angiodysplastic lesions were coagulated for bleeding prevention in the second portion of the duodenum. Pathology did not reveal any concerning findings. The patient made a good recovery and remained stable without any further episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding.

DISCUSSION

Demand ischemia, also known as ischemia due to inadequate blood supply, can occur as a result of significant blood loss, as was the case with our patient. Demand ischemia occurs when the oxygen demand of tissues exceeds the available oxygen supply due to decreased blood volume from acute blood loss.6 This can lead to insufficient oxygenation and perfusion of vital organs and tissues. The severity of demand ischemia depends on the extent of blood loss and the individual’s compensatory mechanisms.

Management of demand ischemia consists of hemodynamic stabilization, where the primary goal is to restore and maintain adequate circulating blood volume. This involves intravenous fluid resuscitation with crystalloids or, in cases of significant blood loss, blood transfusion.7 Monitoring of vital signs, including blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation, is essential to guide fluid management.7

Administration of supplemental oxygen can help improve tissue oxygenation and alleviate demand ischemia. Oxygen therapy should be titrated based on the patient’s oxygen saturation levels. Further, patients with demand ischemia due to blood loss should be closely monitored for signs of organ dysfunction or failure. Continuous monitoring of vital signs (including blood pressure and heart rate), urine output, and laboratory parameters (such as hemoglobin and hematocrit levels), is crucial to assess the response to treatment and guide further management.

A 2019 systematic review of 41 studies including 58,678 patients reports on the increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding with ticagrelor and prasugrel. These third-generation P2Y12 inhibitors were associated with a higher risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when compared with clopidogrel (RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.13-1.46).8

The underlying cause of blood loss should be identified and addressed promptly. In our patient’s case, this involved discontinuation of the anticoagulant medication and referral for endoscopy. Blood loss and demand ischemia can lead to various complications, including coagulopathy, acute kidney injury, and metabolic disturbances.1 These complications should be recognized and managed promptly to optimize patient outcomes. Fortunately, our patient made an excellent recovery and remained stable at 6-month follow-up.