Background

Massive hemoptysis, the expectoration of high volumes of blood, resulting in significant airway obstruction, abnormal gas exchange, or hemodynamic instability, is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Thus, rapid recognition and treatment are imperative to successful management. Initial life- saving measures include intubation and ventilation alongside repositioning of the patient, ensuring hemodynamic stability, and correcting bleeding diathesis. Tranexamic acid (TXA) in a nebulized form is one method of hemoptysis correction given its use as an anti-fibrinolytic agent in the treatment and prevention of major bleeding. Current literature on the use of nebulized TXA exists largely in the context of treatment of epistaxis and post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage. However, there are few studies available that evaluate its use for management of hemoptysis, or a pulmonary source of hemorrhage, warranting further research. The use of nebulized TXA is beneficial for patients, especially those with restricted upper airways, as it is a means of noninvasive therapy to mitigate the need for a high-risk intubation. Of the few existing studies, one randomized controlled trial treated patients with non-life-threatening hemoptysis with inhaled TXA, resulting in decreased blood loss, faster resolution, and shorter hospital stay when compared to those treated with inhaled normal saline 2. Using a case study as an example, we aim to further discuss the utility of TXA in the stabilization of patients with persistent hemoptysis.

Case Presentation

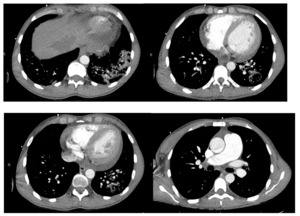

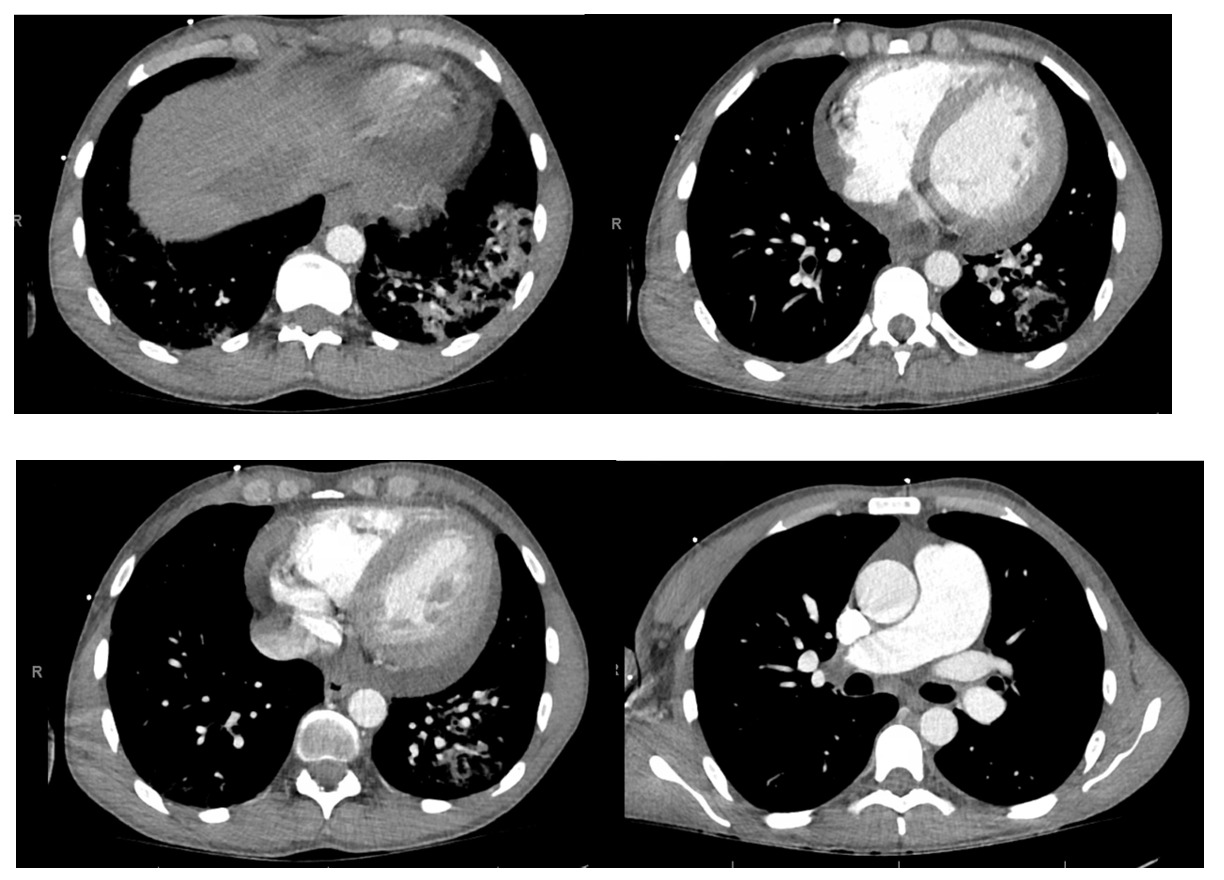

The patient is a 32-year-old male with a history of end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis secondary to a distant history of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis who presented to the emergency department due to hemoptysis. He reported that two weeks prior he had a similar episode but it self-resolved. He had no fevers or sick contacts. Family history revealed that he had a sibling who recently expired from pulmonary complications of dermatomyositis. The patient was in clear distress from persistent hemoptysis with evidence for upper airway edema including stridor and hoarseness. He experienced brief syncope twice. Due to his presentation and concerns of instability we discussed intubation with our patient and he expressed hesitancy and became emotional due to his sibling’s recent passing following intubation. Alternative measures for stabilization were considered and nebulized tranexamic acid was administered. This resulted in swift improvement of coughing episodes and resolution of hemoptysis. The intensive care unit was consulted, and the patient was admitted in stable condition. There was no relapse of hemoptysis during his hospital course. During admission, the patient was electively intubated for bronchoscopy with cryotherapy for clot removal from the upper and lower airways. Chest radiography demonstrated interstitial opacities of the lung bases bilaterally (Figure 1). Chest computed tomography angiography confirmed left lower lobe pneumonia with cavitating pulmonary nodules, without evidence of pulmonary embolism (Figure 2). Autoimmune workup was significant only for myeloperoxidase antibodies. Respiratory culture was positive for P. aeruginosa and Methicillin-sensitive S. aureus. The patient was diagnosed with hemorrhagic pneumonia, treated with broad spectrum antibiotics, and discharged with follow-up for further outpatient workup.

-

Left lower lobe pneumonia.

-

Cavitating pulmonary nodules measuring up to 15 mm in mean diameter, suspicious for septic emboli or cavitary pneumonia. Cavitating metastases are also in the differential diagnosis. Additional non-cavitating pulmonary nodules measuring up to7 mm.

-

Cardiomegaly and small to moderate-sized pericardial effusion.

-

Enlargement of the main pulmonary artery is suggestive of pulmonary hypertension.

-

No evidence for pulmonary embolism

Discussion

In our patient, the presence of concomitant airway edema raised concern for life-threatening hemoptysis and the need for urgent intervention. Traditionally, the etiology of hemoptysis has been difficult to diagnose given

the multitude of pathologies. In our patient, who was ultimately diagnosed with hemorrhagic pneumonia, there is still a question of whether or not the underlying cause of his hemoptysis has an immunologic basis especially given his family history of dermatomyositis. One consideration would be granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener’s granulomatosis). Emergency medicine focuses on stabilization of the patient, with an additional focus on overall morbidity and mortality. Nonetheless, early measures to control the bleeding in the emergency department, regardless of etiology, can have a significant impact on outcomes. Although intubation and ventilation is viewed as a necessary step in management of patients with life-threatening hemoptysis, our patient voiced great hesitancy towards this intervention, so timely consideration was given to other treatment alternatives. TXA is a useful tool that can be considered in all cases of bleeding. Given its routine use to mitigate bleeding in hemorrhaging patients, we postulate its use in acute hemoptysis can be efficacious. It is important to note that sedation and intubation carry risks such as hypoxia, cardiovascular collapse, ventilator-associated pneumonia, and others which could be avoided by stabilization with nebulized TXA. It is also important to recognize, though, that nebulized TXA could create difficulties down the line for subsequent intubation and bronchoscopy in the critical care setting.

There are several concerns we consider. Clearing blood via bronchoscopy and therapeutic suction in intubated patients poses a greater challenge as compared to an awake and alert patient who has a strong cough reflex and can more efficiently clear blood from their airway. Additionally, nebulized TXA is unlikely to reach a very distal source of bleeding, but it does cause the blood that is present in the airways to coagulate rapidly. This would further contribute to the difficulty a patient may have in clearing the blood on their own. Although bleeding may stop due to tamponade by this obstruction, if bleeding does continue, it will be even harder to clear the airways and rescue the patient, or for the patient to clear their own airways and rescue themselves. Consequently, in our patient bronchoscopy cryotherapy was employed to remove the resultant TXA clot the following day; a method by which freezing the clot with cryo-probes facilitates removal. If TXA had not been used, it is possible that the source of bleeding could have been directly visualized with more ease. This would allow the proceduralist to navigate the airways, locate the source of bleeding, and directly intervene to curate a treatment plan most specific to the now-evident underlying pathology versus our patient whose hemoptysis was ceased but the exact cause is still postulated. Despite several arguments against use of nebulized TXA, there are existing studies that support the use of this modality. Although current literature reports use of TXA for hemoptysis, it is given in IV or oral forms 1; fewer studies exist evaluating a nebulized mode of administration. There are several case reports and case series on patients with hemoptysis due to varying etiologies that displayed cessation of bleeding with nebulized TXA, with the maximum resolution time being fifteen minutes 1. Doses in all of these studies have ranged from 250mg to 1000mg, however each patient achieved resolution of their symptoms. Cochrane Review analyzed a randomized controlled trial that compared nebulized TXA to IV and oral forms, with nebulized normal saline serving as the placebo. Neither IV nor oral TXA led to resolution within 7 days when compared to the placebo, however the duration of bleeding episodes was shortened with nebulized TXA 3. Although our patient had a good outcome, it is difficult to attribute that to the nebulized TXA, which certainly played a role, but the risk-versus-benefit must be weighed.

Recommendations by intensivists include stabilizing with emergency intubation, positioning the bleeding lung down to prevent aspiration into the unaffected lung, or stat consultation of thoracic surgery or interventional pulmonology with definitive treatment being bronchial artery embolization. Nebulized TXA could surely be reserved for patients with definitive do not intubate orders or those with contraindications to aggressive critical care. The antifibrinolytic properties, low side-effect profile, and low costs lend TXA to the off-label use in hemoptysis, but studies to encourage the routine use of inhaled TXA in hemoptysis remain insufficient.

Conclusion

Tranexamic acid was successfully used to manage hemoptysis in this case, and should be considered part of the armamentarium to attenuate bleeding, especially when intubation is not desired.

List of Abbreviations

TXA: tranexamic acid

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been granted an exemption from requiring ethics approval by Orlando Health Institutional Review Board. We certify that the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

Not applicable

Authors’ contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: CV, RB; data collection: CR, RB; analysis and interpretation of results: CV, RB, PF; draft manuscript preparation: CR, RB. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr. Philip Flaherty MD (Critical Care Physician) for his assistance and insight into the critical care aspect of management of these patients.