Practice Innovation

Traumatic HTX/PTX management has changed substantially in the last decade. Traditionally, large-bore thoracostomy tubes have been used to treat traumatic HTX/PTX. However, little evidence supports the continuation of these practices. Recent studies show that smaller thoracostomy tubes, such as pigtail catheters, are as effective as large-bore tubes in hemodynamically stable patients and are associated with decreased adverse effects.1–4 Despite this evidence, there is still significant variation in practice across and even within institutions.1–3 There is an ongoing need to change the paradigm and educate providers about best practices for the treatment of traumatic HTX/ PTX.

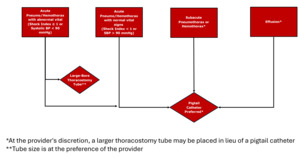

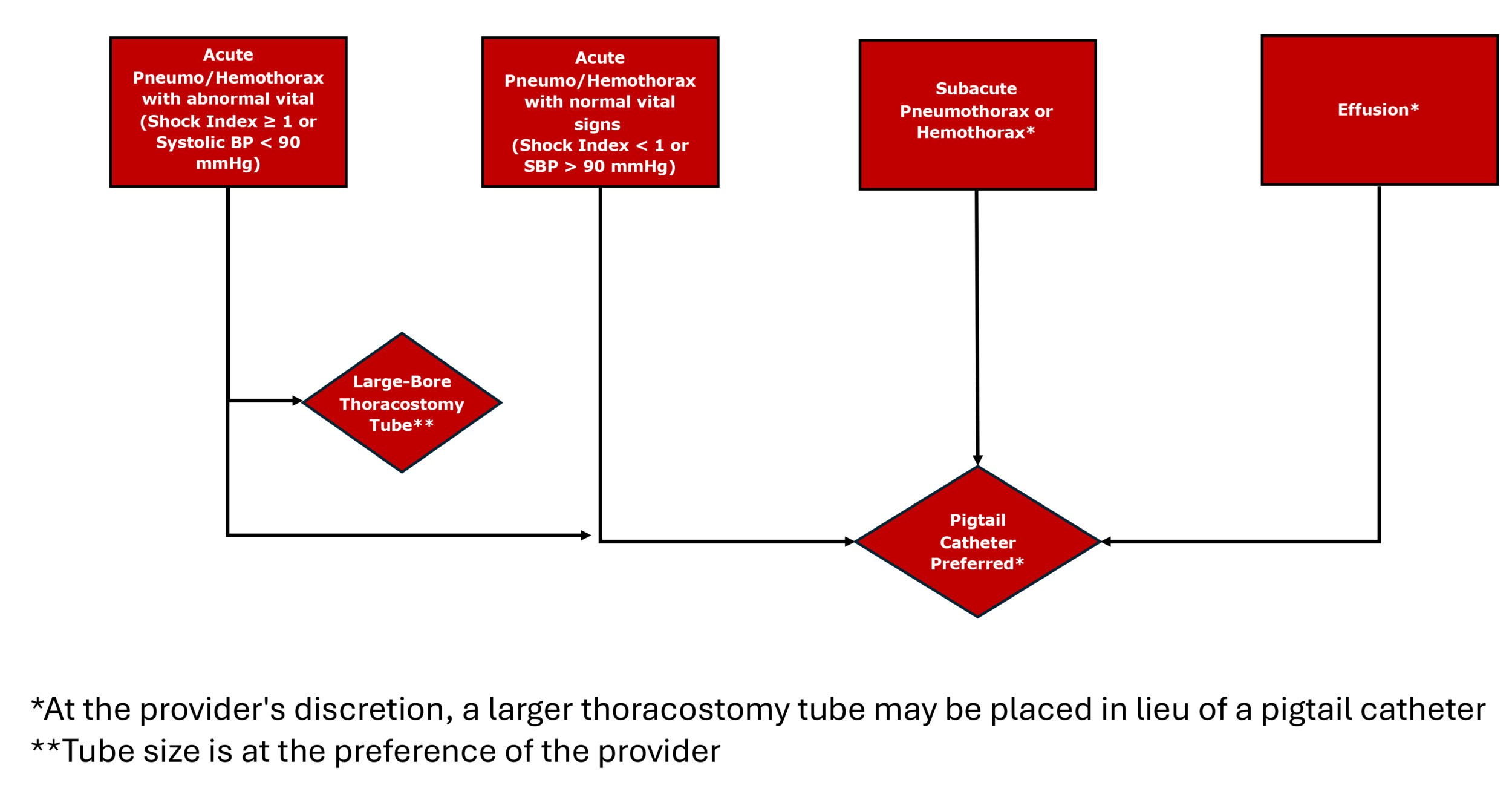

We at NewYork Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Center, a level 1 trauma center, utilized a quality improvement approach to address this within the institution. Our emergency department sees more than 140,000 patients annually. We developed an institutional guideline (Figure 1) through collaboration between the Surgery and Emergency Medicine departments to standardize the size of thoracostomy tubes placed for traumatic HTX/PTX. In December 2022, the guideline was implemented using multimodal provider messaging. The algorithm was discussed in daily multidisciplinary trauma huddles, posted in the resuscitation bay where thoracostomy tube supplies are stored, and posted as a practice change alert in the electronic medical record (EMR).

The authors developed a project to study how the guideline affected clinical practice and if it would reduce the placement of large bore thoracostomy tubes without adverse patient outcomes. We included patients over 18 years of age admitted with thoracic injuries resulting in HTX or PTX treated with a chest tube from January 2022 to November 2023. Patients were identified through ICD codes in the trauma registry and electronic medical record. The primary outcome was adherence to the newly developed guideline for placing thoracostomy tubes. Conversion from pigtail to larger-bore chest tube and other adverse events were secondary outcomes.

We tracked the selection of chest tubes pre-and post-implementation of the guideline and identified a trend; however, there was not 100% compliance. We identified 18 pre- guideline and 27 post-guideline HTX/PTX meeting the criteria. Before the guideline, 15 out of 18 patients (83%) received care consistent with the guideline (no large-bore chest). After implementation, 25 out of 27 patients (93%) received care consistent with the guideline. None of the patients in the pigtail cohort experienced documented complications or required conversion to a large bore thoracostomy tube. We noted that there was a significant lack of quality documentation regarding deviation from guidelines.

Discussion

Although we believe the intervention demonstrates progress, there is still room for improvement in the standardization of tube thoracostomy in acute trauma (especially when treating hemothorax). Our experience suggests that educational interventions would benefit from associated system-level interventions to motivate late adopters. For example, we noted the lack of quality documentation regarding deviation from guidelines during data abstraction. To address this, a proposed quality improvement intervention might consist of an EMR best practice alert triggered by vital signs and shock index requiring subsequent documentation for the rationale of large-bore chest tube placement. Routine QA case review of all large-bore chest tube placements may also identify areas for institutional improvement and encourage provider compliance with best practices.

In short, we suggest institutions adopt similar guidelines but recommend that provider- level education be paired with systems-based interventions and provider feedback to ensure best practices that benefit patients and their outcomes.