Introduction

The Bureau of Family Health and Nutrition indicates that perinatal mental health concerns are highly prevalent.1 Their research shows that one in seven women experience symptoms of depression/anxiety either during pregnancy and/or during the postpartum period.1 Risk factors for postpartum anxiety include: previous mood disorders, education level, negative perinatal experiences, lack of support, and low maternal self-efficacy.2 Furthermore, research shows that 13%-19% of new moms develop a more serious clinical condition such as postpartum depression.1 Research shows that factors associated with a higher risk of depression include: a history of depression, a language spoken at home at is not English, poor current health of the mother, and low maternal self-efficacy.2 Maternal postpartum depression can have wide-ranging adverse consequences, affecting both mothers and their offspring. It impairs maternal functioning and can disrupt crucial aspects of mother-infant interactions, such as breastfeeding, bonding, and childcare.3 Additionally, it strains the mother’s relationship with her partner and, in some cases, can lead to suicidal ideation and behavior.3 Postpartum depression can also adversely affect the child’s well-being, leading to problems like poor nutrition, health issues, and abnormal development. Cognitive impairments in the offspring, including deficits in general cognitive performance, executive functioning, intelligence, and language development, have been linked to maternal postpartum depression, where longer episodes of depression have been associated with poorer cognitive performance in children compared with shorter postpartum episodes.3

Fortunately, there are various approaches and resources mothers can use to improve their mental health. A meta-analysis published in 2020 found that women who received technology-based telemedicine had a statistically significant improvement in postpartum depression.4 Some of these interventions included telemedicine via telephone (and/or text messages) or internet-based therapy such as online psychoeducational sessions or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, mobile applications, emails, video conferences, social media platforms, and online chat.4 Furthermore, a systematic review published in the British Medical Journal found that physical activity and rates of postpartum depression are negatively associated indicating that exercise can also be beneficial for maternal mental health.5 Moreover, another resource that has proven to be beneficial to women suffering from postpartum depression is increased social support.6 Social support is defined as “the emotional, psychological, and/or physical support provided by another person”.6 This can often include family, friends, and neighbors.6 Lastly, a study published in Psychological Reports indicated that expressive writing can be a valuable and cost-effective intervention to prevent postpartum depression in women by offering support for their mental well-being.7 An example of expressive writing includes taking 15 minutes a day, three days a week, to journal inner thoughts about specific stressful events that occurred to the writer.7

Although there are several approaches and resources for people who are experiencing postpartum anxiety/depression, oftentimes they are not made aware of these methods or local resources available to them. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that pediatricians screen mothers for PPD at infant well-child visits during months 1, 2, 4, and 6.8 Since pediatricians specialize in the health of children, very few know how to support women suffering from PPD beyond the general recommendation to seek professional help. Our hypothesis is that with exposure to an educational intervention where current research and resources regarding support for women with PPD is synthesized and presented to pediatricians, their knowledge on available tools accessible to mothers will increase. We developed an educational intervention in the form a presentation that detailed current research and local/national resources for women with postpartum depression. We presented this to pediatric residents at the Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children in Orlando. Our aim is to ensure that pediatric resident physicians in the Orlando area have some information on where mothers can go and what they can do if they screen positive for or display symptoms of postpartum depression.

Methods

Pediatric residents at Orlando Health Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children were invited to participate in our quality improvement study focused on awareness and knowledge regarding postpartum anxiety and depression. The residents who opted into the study received one educational intervention in person for one hour during a didactic session at the hospital. The pediatric residents regularly attend weekly didactic sessions during lunch on Wednesdays consisting of one-hour presentations on various topics in the field. Our presentation focused on the epidemiology of postpartum depression, local and virtual organizations that provide support for new mothers, and resources individuals can utilize if they screen positive for postpartum depression.

Prior to the start of the session, the resident participants were provided a Qualtrics link for an anonymous pre-survey consisting of nine questions. Immediately after the educational session was completed, the residents were given a second Qualtrics link for an anonymous post-survey consisting of the same nine questions. The survey links were displayed using two different QR codes: one sheet of paper had a QR code for the pre-survey and another sheet of paper had the second QR code for the post-survey. The papers were placed on the desks of the residents prior to their arrival, and a brief introduction was given at the beginning of the presentation. The residents completed both surveys by scanning the codes with their phones. The survey questions evaluated the level of understanding and knowledge gained and retained by the participating participants. To increase response rate, residents completed both surveys within the same didactic session.

Using a plan, do, study, and act (PDSA) model, we first established clear objectives and processes of our quality improvement project.9 We then implemented the plan by coordinating with the Arnold Palmer Hospital pediatric residency program director to organize a date and time of the presentation. We sent our presentation to the director ahead of time to ensure accuracy and relatability of the content and receive any constructive feedback for edits. We further analyzed the study design by collecting and measuring results. Through pre- and post-survey responses, the quality improvement study obtained quantitative and qualitative data to assess the learning acquired by the pediatric residents. For the qualitative approach, we analyzed the residents’ current knowledge with a “yes” or “no” response regarding their awareness of postpartum depression and how familiar they were with local and virtual resources. The research conducted involved descriptive statistical analyses that allowed for a question-by-question comparison. Through descriptive statistics, we used frequency distribution represented by numerical and graphical summaries of data to help describe, understand, and interpret the characteristics of our dataset. We evaluated an increase in knowledge scores through this comparison of pre- and post-responses. They provide information regarding the dispersion and variability of responses among the residents through the illustration of histograms.

Results

The results of the pre- and post-surveys demonstrated the degree of awareness and knowledge gained by pediatric residents after the implementation of our quality improvement presentation focused on research and resources pertaining to women suffering from postpartum depression. The study showed that about the same percentage of residents believed PPD is very common before and after the presentation, 85% and 89% respectively.

At the start of the informational session, 33% of participants thought there is ongoing PPD education provided to healthcare staff. Residents were more confident about what score is considered PPD on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), and 89% of them responded correctly with a score of 10+ after the presentation in contrast to 77% of the participants at the start of the session (figure 1). Moreover, 54% of residents responded that they always screen for PPD while 46% of them screen often. About 48% of the participants recommend self-care routines, 17% meditation, 13% exercise, 9% yoga, and 13% journaling, gardening, and reading for people with PPD.

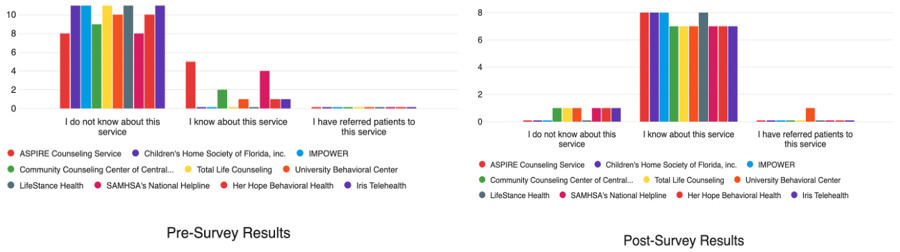

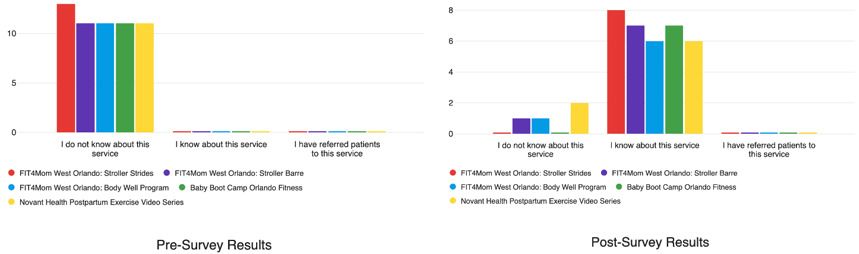

Average knowledge scores of participating residents increased by about 87% on pooled analysis from pre to post educational session. Specifically, there was an 80% average increase in knowledge scores regarding ten different telemedicine therapy options available to women (figure 2). Furthermore, there was an 88% average increase in knowledge scores regarding local support group options for peripartum women (Figure 3). Lastly, a 90% average increase in knowledge scores regarding eleven virtual support resources and five physical exercise programs specific to postpartum mothers (Figures 4,5).

Discussion

Based on the results, the residents who filled out both the pre and post surveys showed substantially higher knowledge of PPD dynamics and resources post intervention. In comparing the pre- to post-survey responses, an overall average of 87 % increase in knowledge scores occurred. Residents after the survey felt they were able to diagnose PPD with Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale more accurately compared to before the intervention (seen by a 12% increase in understanding the correct depression scoring). There was over 80% increase in resident knowledge scores regarding telemedicine and local support groups for women.

The study’s internal validity is limited by several factors. The sample size is less than 20 for both the pre- and post-survey. Additionally, we received 5 fewer responses because some participants did not complete the post-survey. This could be potentially due to the length of the surveys. If this project were to be repeated, this project should be done on a larger scale across multiple residency programs to increase the power of the study and hence the generalizability, the post survey questionnaire should be sent again to the residents to complete if they did not complete it immediately after.

Conclusion

In conclusion, presenting to pediatric residents helped to increase the awareness and knowledge of new research and resources supporting women suffering from postpartum depression. Further research could include conducting interventions with other residency programs such as OBGYN, internal medicine, and psychiatry. We can apply the changes based on our results and share valuable insight to different residency programs regarding research and resources available to better support those experiencing postpartum depression.

We were able to accept our hypothesis that creating an educational intervention where current research and resources regarding support for women with PPD is synthesized and presented to pediatricians, their knowledge on available tools accessible to mothers will increase.

_is_considered_ppd_.png)

_is_considered_ppd_.png)